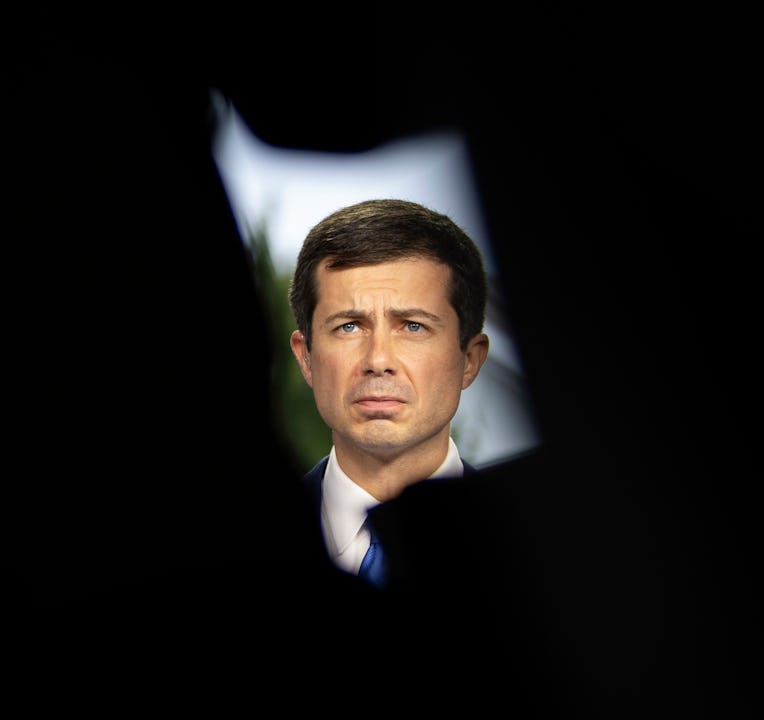

I Did Not Have High Hopes for 'Mayor Pete'

It failed to live up to even those

To answer the most pressing question: no, we do not see Pete Buttigieg, or anyone else for that matter, do the “High Hopes” dance in Mayor Pete. The song appears once or twice in the 96-minute documentary, which follows the former mayor of South Bend, Indiana, and Democratic presidential candidate on the campaign trail from early 2019 until he dropped out just before Super Tuesday. When it does, it’s mostly in the background of rallies or other events, where the song was all but unavoidable; an anthem for the Buttigieg campaign more broadly: a little forced, a lot irritating. This exclusion spares viewers from having to revisit the tragically “white aunts who rap” viral performances, which experienced the kind of exposure that sends publicists to therapy. It also illustrates director and producer Jesse Moss’s — the guy who made Boys State — approach to chronicling the campaign: eliding all details ugly or embarrassing unless they become so omnipresent the camera can’t avoid them.

The movie, which starts streaming on Amazon Nov. 12, features interviews with Buttigieg himself, as well as an array of surrogates, including his husband Chasten and his strategist, Martin O'Malley campaign veteran Lis Smith. Other appearances include: an exceedingly warm Joe Biden cameo, Rev. Al Sharpton, many supportive fans, and a few less supportive ones — some Trump guys and an evangelical protestor who sees every vote for Buttigieg as a “lash on Christ’s back” (this is accompanied by a Jesus impersonator actually getting whipped). As perhaps the latter example indicates, the documentary is focused above all else on Buttigieg’s struggles with his own sexual identity, as a small-town, midwestern veteran who didn’t come out until age 33.

Buttigieg’s recollections of his closeted life can be sincerely moving; in one speech, he remembers times when, if shown the part of his body that made him gay, he would have “cut it out with a knife.” But if the mayor himself, as he observes in one press conference, was surprised by how little voters seemed to care about his marriage, Moss does not share the sentiment. The documentary foregrounds Buttigieg’s identity over basically everything else — his time as mayor, his military service, his questionable credentials as a former McKinsey consultant, his presidential platform, and even the needling, Rhodes Scholar intellectualism that drove so much of his support.

That’s not necessarily surprising for a documentary of this kind, which is, of course, tasked with showing the man behind the performance — the personal is political, etc. But when the former crowds out the particulars of the latter, it does raise the question: What the fuck are we doing here? Put another way: What purpose does a campaign documentary serve? Especially when that campaign failed. Politicians, universally vile in constitution, are slippery to the point of cliché; taking any of them at their word risks verging into propaganda. An honest depiction must go beyond political talking points — exposing hypocrisies, asking pointed questions, or at the very least, showing viewers something they don’t already know. This never really happens in Mayor Pete.

An easy point of contrast might be Knocking Down the House, Rachel Lear’s 2019 documentary about four grassroots campaigns each aiming to install progressive outsider women in Congress. Much like Moss, Lear began shooting in the nascent stages of these elections, when their candidates were virtual unknowns; also like Moss, one of Lear’s subjects, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortes, would become a national celebrity before the documentary was released (one could argue that Lear became slightly too conscious of this fact in post-production, foregrounding AOC’s campaign over her three peers — Cori Bush in Missouri, Paula Jean Swearengin in West Virginia, and Amy Vilela in Nevada — who lost their respective races; Bush, of course, would win two years later). But unlike Moss, Lear began her project with a larger goal: not merely profiling these women, but following two offshoots of the 2016 Sanders campaign, Brand New Congress and Justice Democrats, that had undertaken to unseat members of their own party. These were insurgents linked by a specific set of policies (mainly: Medicare for All), and a shared disdain for corporate cash. The film’s central tension was not in degrees of inspiration from the women’s respective underdog stories, though there were plenty of those moments, but in the implicit question: Can this movement work? For three of them, it didn’t.

In asking, however, Lear not only examined the bigger ideas the campaigns would want to implement, but those they opposed. In one prescient scene, Lear filmed Sweringen in a town plagued by cancerous pollution from coal extraction; her opponent, former coal executive Sen. Joe Manchin, had taken $700,000 in mining money to fend her off. By contrast, the main question Moss asks seems to be, “What’s Pete Buttigieg really like?” His policies are an afterthought in Mayor Pete, in the sense that they barely come up at all. There’s a brief scene on Buttigeg’s wonkish interest in capital-P-policy — at one point, he mentions loving PivotCharts — but his marquis proposals, from the fatally technocratic “Medicare For All Who Want It” to the more ambitious notion of adding six justices to the Supreme Court, go entirely without mention. The question of whether, as Buttigieg often put it, “a Maltese-American, left-handed, Episcopalian, gay, war veteran, mayor and millennial” can win the presidential election seems irrelevant without a clear sense of what he would do if he won. But maybe Moss isn’t entirely to blame for that; the campaign never had an answer either.

If specific policies aren’t the focus of Moss’ movie, there are times when political strategy seems to be. Some scenes are clearly striving for the fly-on-the-wall frankness of The War Room, the 1993 documentary about James Carville and George Stephanopoulos’ mind games during Clinton’s first presidential campaign. In an early meeting, for example, as Buttigieg, Smith, and other staffers plot out his initial marketing, the candidate suggests they play up his biography — small town Indiana boy, joined the military etc. — before noting: “We’ve got to make sure that doesn’t read as very white.” The scene immediately cuts to his photo opp with Rev. Al Sharpton. You could take that as a wink at the viewer, a moment where the gears of the P.R. machine were laid bare. But it's quickly lost in uncritical, press conference platitudes: Buttigieg on finding unity in otherness; Sharpton on homophobia in the Black community.

Later, when Buttigieg fields one of the strongest, most infuriating challenges to his candidacy — the murder of Eric Logan, a 54-year-old Black man, at the hands of South Bend police — there are again some subtle critiques. In one scene, Smith and some strategists chide his dead-eyed affect; in another, Moss rolls footage of the infamous town hall where activists eviscerated his lack of action. But these too find neat resolution: staffers praise the bravery of facing his own constituents; Buttigieg muses on his struggles seeming “real or authentic.” The section ends on a CNN panel discussing his debate remarks about the murder. “He wasn’t deflecting,” says Anderson Cooper. David Axelrod adds: “I think that was an important moment for him.”

The achievement of The War Room was in its straight-faced portrayal of political theatrics. However you felt about Carville, Stephanopoulos, or the candidate they fought for (I feel negatively about all three), they come off as neither heroes nor villains, so much as manic players in a game they have heavily studied, but still only sometimes understand. Their morals are loose; their strategy veers from smart to pretty stupid. Moss had an amazing opportunity to probe the underbelly of political consultation — specifically at the movie’s apex: the disastrous Iowa Caucuses, where Buttigieg prematurely declared victory; and the subsequent collapse of his campaign, after which he joined Amy Klobuchar and Beto O’Rourke in rallying the moderate establishment around Joe Biden.

There is a single hint of this: it is Lis Smith, surprisingly, who cautions Buttigieg against making his victory speech. The rest is amazingly selective. Bernie Sanders briefly ribs Buttigieg’s timing (his sole appearance in the entire documentary, save a single reference to the “runner up” from 2016); Pete promises to go to New Hampshire “victorious.” There, he celebrates his momentary lead, then quickly concedes. The Nevada caucuses aren’t mentioned at all (perhaps because Buttigieg won just three delegates); the South Carolina primary appears only as Buttigieg’s rationale for dropping out. In the aftermath, reeling from the loss, the camera shows Buttigieg picking up a call from a man identified only as “Mr. President.” Then Chasten’s phone rings; it’s Jill Biden. Eventually, both pass the phones to their spouses. Viewers can hear Buttigieg talking to the muffled voice of the future president.

These last few scenes are especially frustrating, because they sidestep the actually interesting questions: how the campaign handled the confusion of a bungled caucus, how they strategized in the days that followed, how they weighed the political calculus of endorsing a candidate — especially one who had lost his first three states. But maybe the answer was obvious. In the final scene, Pete and Chasten stroll along the national mall, as a voiceover plays. It’s now-President Joe Biden announcing his nominee for Secretary of Transportation.