Welcome to Net Positive, a series about nice places and things on the world wide web.

Many features of American democracy are disappearing before our eyes: the right to decide what to do with your own body; the right to be safe from concealed firearms; the right to be free from group prayer at public school; the right to inhale clean air. I am so furious I can hardly breathe the shitty air we already have. But deadlines do not evaporate during societal collapse, so I am here to tell you some good news. There is at least one widely hated facet of civilization that will soon go blessedly extinct: the CAPTCHA (aka the “Completely Automated Public Turing Test to Tell Computers and Humans Apart”).

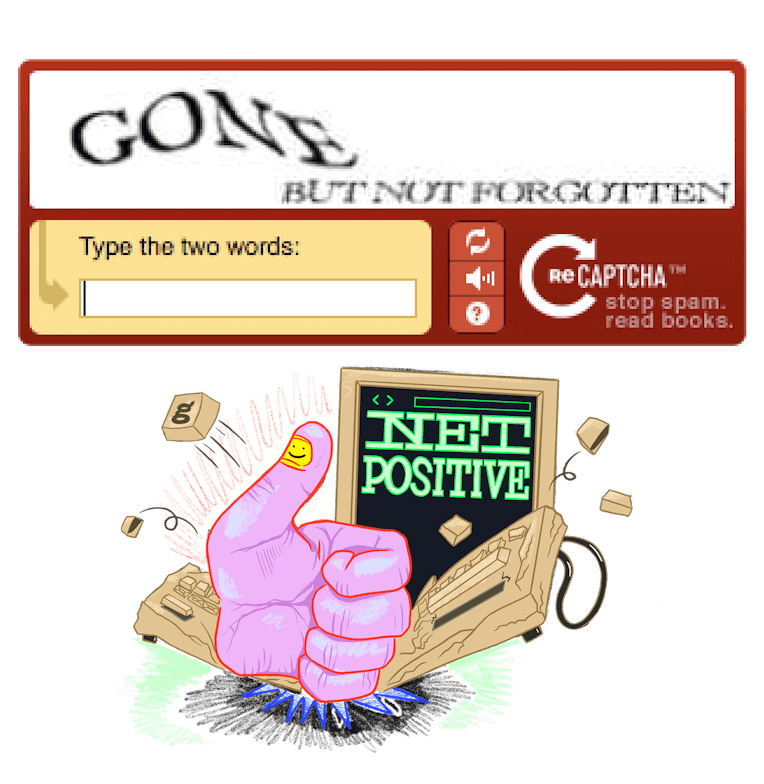

For the unfamiliar, CAPTCHAs are those little boxes that ask users to promise “I am not a robot,” and then prove it by identifying grainy pictures of bicycles or typing out visually distorted gibberish. The unfamiliar are likely a minority here, as CAPTCHAs are an omnipresent feature of the modern internet. But those inhuman humanity verifiers, like our basic civil rights, may be mortal after all. As a Guardian headline put it last week: “iOS verification update marks end of ‘captchas.’”

An upcoming feature across all Apple operating systems, called “automatic verification,” will allow websites to identify human users independently. (It’s unclear whether other operating systems will follow suit. But the Guardian pointed out that Google has already adopted a version of this technology, though primarily to let “third parties build their own Captcha replacements, rather than ending the technology altogether.”) If executed as promised, Apple users will no longer have to slide puzzle pieces into cartoon outlines, or squint at small boxes to see which contain a boat. Instead, their device will submit encrypted statements to the website in question, confirming its operator is in fact flesh and blood. There’s a touch of grim optimism to this proposal: in at least one way, it’s an asset to be alive.

By most definitions, CAPTCHA has not been with us long; in internet years, it is roughly middle-aged. The concept dates back to 1997, when two teams of researchers set about designing an algorithm to distinguish spam bots from people. One group, working at the search engine AltaVista, created a series of word puzzles to prevent bots from adding unapproved URLs. Another team, at the IT security company Sanctum, built similar tests that tasked users with, per their patent application, the “identification of objects and letters within a noisy graphical environment.” The latter group is typically credited with nailing it first — they submitted their patent application in 1997, while AltaVista’s was approved the following year. But neither called their puzzles “CAPTCHAs.” The term wouldn’t emerge until 2003, when four researchers at Carnegie Mellon coined it in a paper, while introducing a CAPTCHA of their own.

The success of that paper brought CAPTCHA to the mainstream. They now lurk in nearly every corner of the online world and in more forms than I can taxonomize here. Because of that ubiquity, CAPTCHAs have acquired a reputation: annoying. They are an added step to anyone’s online mission, an obstacle in a fast and increasingly fiber optic environment. There is also a sinister element to their operation. In 2009, Google bought reCAPTCHA — a software program developed by one of the Carnegie Mellon scientists that coined its namesake, which repurposed the algorithm to help digitize scanned documents. With reCAPTCHA, the fuzzy PDF of an old page could be converted to a searchable text file, one user authentication at a time. Google acquired it to help transcribe their archive of old books. They have since applied it to other visual projects. These days, identifying bridges by CAPTCHA is basically intelligence gathering for Google’s self-driving cars.

In spite of these obvious and brazen flaws, I have always found CAPTCHA charming. There is something anachronistically amateur about them, both in form and in function. As aesthetic objects, they are unambiguously ugly: clunky, lo-def, redolent of a Usenet forum or Mike Pence’s old personal website written in Comic Sans. In our climate of Apple-imposed techno-minimalism, CAPTCHA remains a relic of the internet’s primitive past. That quaint impression is aided by the fact that, as a tool for identifying bots, CAPTCHA is equally unsure of its own utility. Why would Google need our input if they knew which boxes had bridges? It seems they often don’t. As my colleague, art director Jack Koloskus, recently pointed out, users can easily subvert the reCAPTCHA request. So long as you identify most of the objects accurately, the system will approve your entry. Anyone can add an unsolicited bus and throw a minor wrench in Google’s data-collection cogs. It’s a trivial rebellion, but for the moment, I will take it.

The thing I love most about CAPTCHA, however, is how hard they can be. The algorithms have largely succeeded in developing puzzles too serious for spam. But in so doing, they have somewhat overlooked the human element. I know this on an anecdotal level. In navigating the internet, I am often confronted with the fact that I am too stupid to prove my own humanity. But research suggests I am not alone here. A study from Stanford, titled “How Good are Humans at Solving CAPTCHAs? A Large Scale Evaluation,” surveyed data from over 318,000 CAPTCHAs, and found that they were “are often difficult for humans, with audio captchas being particularly problematic.” In a sample of three people for example, they found the subjects agreed on the correct answer just 71 percent of the time. That number sank to 31 percent for audio CAPTCHAs. Perhaps obviously: accuracy declined among non-English speakers, younger respondents, faster respondents, and those without Phds. We may not be robots, but we’re less advanced than we think.

In that sense, CAPTCHA is a tidy allegory of American government: annoying, ugly, ineffectual, predatory, nostalgic, a daily confrontation with our own idiocy. Of course it’s dying out.