The Atlantic Wants Biden to Go Full Kissinger

May he rest in peace — wait what?

The Atlantic published an article this morning titled “What Joe Biden Could Learn From Henry Kissinger.” It was written by Martin Indyk, a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and former U.S. ambassador to Israel, whose distinctions include, according to the Los Angeles Times, being “the first serving U.S. ambassador to be stripped of government security clearance.” He later got it back and went on to write this piece, which includes the word “relentless” eight times.

The catalyst for Indyk’s suggestion was Biden’s recent “Aukus” pact with Australia and the U.K. — an agreement to share nuclear-powered submarine intelligence in a bid to strengthen the U.S.’s military allies in the Indo-Pacific. This screwed over France, which had already been negotiating a submarine deal, and produced Gawker’s favorite quote from Boris Johnson:

I just think it’s time for some of our dearest friends around the world to prennez un grip about all this and donnez-moi un break because this is a fundamentally a great step forward for global security.

But Indyk can’t see the upsides to the situation, like that quote, which is why he starts the third paragraph like this:

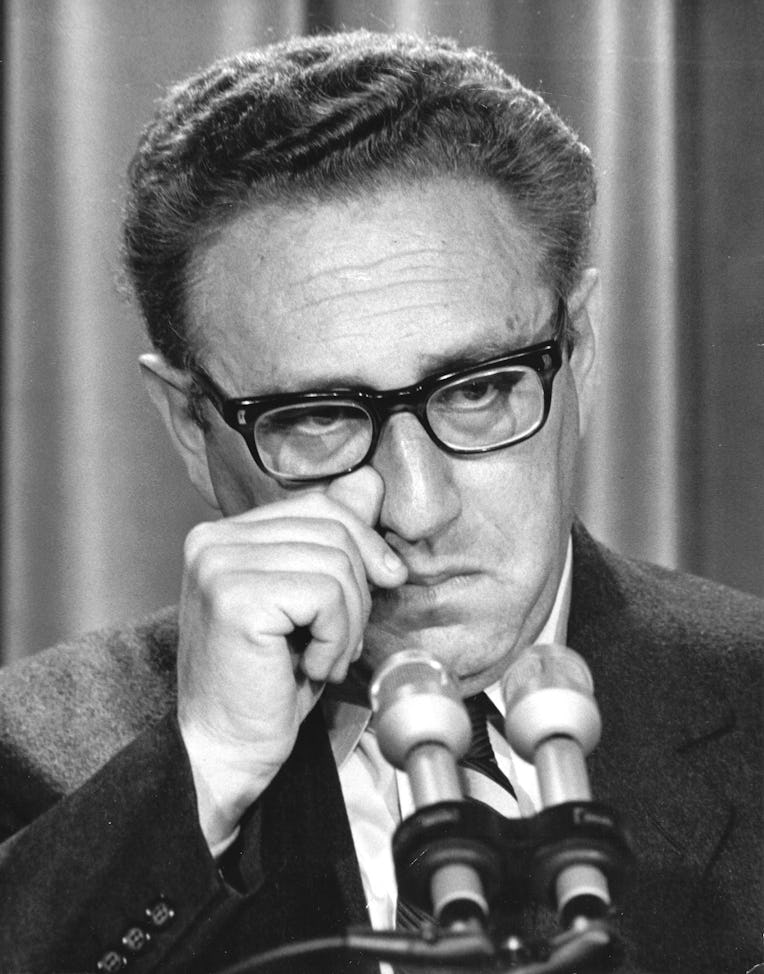

Perhaps Biden could learn something from America’s most accomplished diplomat, Henry Kissinger. At 98, Kissinger remains a controversial figure, his realpolitik brand of balance-of-power diplomacy reviled by some for its application in Laos, Cambodia, Chile, and Bangladesh, but revered by others for achieving the opening with China and détente with the Soviet Union.

That “application” referenced here included the carpet bombing of Cambodia and Laos — both neutral states during the Vietnam war — in campaigns kicked off in secret and sustained for several years that rained some two million tons of explosives on Laos and another 540,000 tons on Cambodia. The death tolls of those bombardments are disputed, but PBS ballparks that anywhere from 150,000 to 500,000 civilians died in Cambodia alone.

But let’s put, as Christopher Hitchens phrased it, the man’s “callous indifference to human life and human rights” aside. Kissinger wouldn’t exercise his “diplomatic skills fully,” Indyk reports, until after all that — when he became secretary of state in 1973. Per Indyk:

His relentless diplomacy in the Middle East sidelined the Soviet Union during the Cold War and produced four Arab-Israeli agreements, which established a new American-led order in that turbulent part of the world and laid the foundations for Arab-Israeli peace.

Those foundations turned out well.

Indyk credits Kissinger’s “success” in the Middle East to several “key ingredients:” He “always began with a clear objective, at least in his own mind, and a strategic concept for how to achieve it.” (Also cited: his “innate conservatism,” and his “study of history.”) In this case, the clear objective was “to build a new, American-led order in the region,” and the strategic concept was to “ameliorate conflicts between competing powers,” not resolve them. “Peace for Kissinger was a problem,” Indyk writes, “not a solution.”

Indyk zeroes in on two agreements Kissinger arranged — one with Israel to cede some territory to Egypt; another with Syria to disengage in Golan Heights, a border region Israel had annexed in 1967. (More recently, Donald Trump recognized this territory as part of Israel, making the U.S. the first country to do so; Netanyahu named a settlement after him later that year). Though Indyk concedes many caveats to the relative successes of these deals, he describes Kissinger’s “territory for peace” strategy in colorful terms. Here he is on the Syria talks:

It was a match of wits and guile unlike any other in Kissinger’s experience as secretary of state. For 30 days, Kissinger shuttled between Jerusalem and Damascus, making 13 trips, with side excursions to Egypt and Saudi Arabia to secure the support of Sadat and King Faisal. It was a dispiriting, frustrating, and exhausting endeavor that put him out on the frontier of American diplomacy without any serious backing from President Richard Nixon—who was by that point completely preoccupied with fending off his imminent impeachment.

Here’s a paragraph on the Israel negotiations:

Convincing the Israelis was painful, difficult, and frustrating, yet Kissinger was indefatigable. Hour after hour, in meeting after meeting in Washington and Jerusalem, he deployed all the arguments in his arsenal, at times with a sense of humor that disarmed his stiff-necked audience, at others with threats that only reinforced their resistance.

(Perhaps it was a stiff neck that led Kissinger, years later, to give a speech at the Ohashi Institute — a nonprofit dedicated to promoting a kind of shiatsu massage — called “Touch for Peace.”)

So what should we take away from “Kissinger’s style of relentless diplomacy” that “required a combination of caution, skepticism, agility, creativity, resoluteness, and guile in the service of a strategy that favored the pursuit of order over grandiose objectives and magical thinking?” Indyk’s suggestions:

- “Significantly strengthen” America’s “military deployments in the Asian arena.”

- Pay “more attention” to the “role of America’s European allies.”

- Join the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

“Any critic who can suck like that,” Hitchens wrote about Norman Podhoretz’ review of Kissinger’s second memoir, “need never dine alone.”