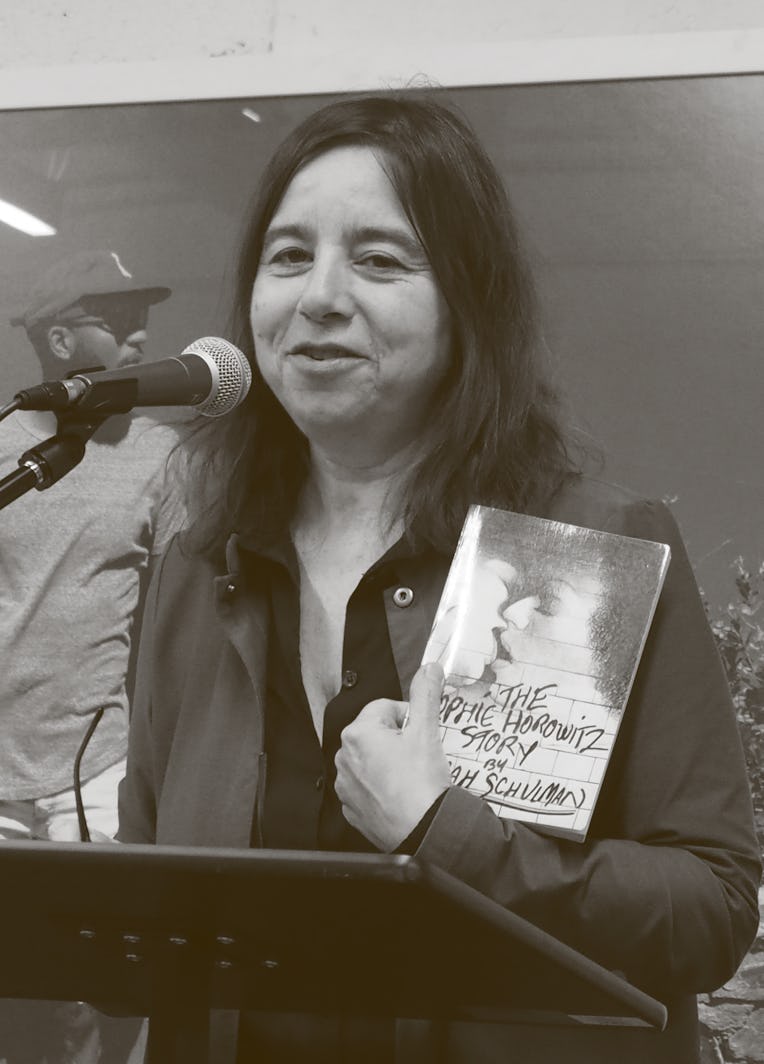

Sarah Schulman: Conflict Is Sometimes Abuse Actually

(If it is a bad review of my book)

Sarah Schulman — the academic and author whose 2016 polemic Conflict is Not Abuse seemed to offer a level-headed alternative to both the conservative free-speech hysterics and fringe liberal language policing that have come to dominate the culture wars — has filed a union grievance against a freelancer over a negative review, sources have confirmed to Gawker.

The complaint concerned a September 2021 essay in the progressive magazine, Jewish Currents, about Schulman’s latest book, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York 1987-1993. The book draws on nearly two decades of interviews — conducted in part for a documentary Schulman produced with filmmaker Jim Hubbard in 2012 — as well as Schulman’s own experience, to tell a 736-page account of the AIDS grassroots group. Among other things, Schulman’s archival history complicates the narrative of ACT UP’s leadership, often attributed somewhat singularly to activist Larry Kramer. The New York Times Book Review described it as “part sociology, part oral history, part memoir, part call to arms.”

When the book came out in May, there was a degree of critical consensus. It was warm. The Times Book Review hailed Let the Record Show as “a masterpiece tome;” over in the Times’ book section Parul Sehgal called it “a tactician's Bible.” Schulman had offered a “corrective intervention in AIDS historiography,” Moira Donegan wrote in Bookforum; or as Joshua Gutterman Tranen put it in The Baffler, “a resounding rebuttal to exclusionary versions of AIDS history.” Even The New Yorker’s Michael Specter — whose approach to this subject might be contextualized by the fact that he authored a “frank hagiography” of Kramer’s public nemesis, Dr. Anthony Fauci, in which he calls the latter “the Enlightenment’s human shield” — found some grounds for praise. “Her labors will provide an invaluable resource,” Specter wrote, “for the social history of the movement that remains to be written.”

A few months after most of the media coverage, Jewish Currents put out a review by Vicky Osterweil, a freelance critic best known for her 2019 book In Defense of Looting. The editors hadn’t commissioned a negative review necessarily, the publication’s editor-in-chief Arielle Angel told Gawker. “We just commissioned a writer that we respect who really knows the beat,” she said. The magazine had, in fact, previously hosted an event with Schulman promoting the book. And when it became clear Osterweil’s piece would be critical, the editors gave Schulman a heads up.

In her piece, Osterweil echoes much of the praise rained on Schulman’s work, calling her research “invaluable” and the separate publication of her interview transcripts (available free online) “an incredible feat of activist archivism.” The essay, titled “What the Record Doesn’t Show,” largely takes issue, not with what Schulman included, but with what Osterweil feels it overlooked:

I want a book that earns and embodies an opening like Schulman’s, which begins, “This is a book in which all people with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) or with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are equally important.” How painful, then, to be a trans person reading and reviewing this book, and to encounter yet another work of trans erasure claiming to be the history of queer resistance.

The crux of her argument follows roughly like this: history gets told by survivors; the survivors of the AIDS crisis were mostly cis white men with better resources; as a result, they tend to be overrepresented in any accounts recorded by the 2000s; thus any post-movement history ought to supplement those recollections with “other kinds of historical evidence.” She concedes that Schulman discusses these limitations at length and draws from many secondary sources. But the book nevertheless “ends up symptomatically reproducing the very exclusions, failures, and violences” of its more conventional predecessors.

There are plenty of opportunities to take issue with Osterweil’s argument (or her occasional overkill on alliteration, as in “queerness promises porous, polymorphous perversities”). In a letter to the editor linked under the article, writer Kay Gabriel expertly counters one of Osterweil’s key examples: Schulman’s critique of a scene in Ryan Murphy’s Pose, which added Black trans activists into a depiction of a famous protest, though Schulman says none were present at the time. Osterweil receives this assessment with “shock and rage,” noting that even if Schulman was right, “surely she can see how transphobic this first appearance of trans women in the book is, where trans women are once again cast primarily as interlopers, recuperators, deceivers.” Here’s Gabriel:

Osterweil reads a transphobic reflex into Schulman’s dismissal of the scene, arguing that this first appearance of trans women in the book casts trans women as “interlopers” and “deceivers.” But this is a misreading. Schulman is in fact targeting Murphy, David France, and other icons of the well-resourced culture industry making bank on a misrepresentation of history; if there’s a “deceiver” depicted here, it’s not Murphy’s fictional trans characters, but Murphy himself.

Schulman took a different approach to reviewing the review. She emailed the editors “a several-page rebuttal asking for either a retraction or factual corrections,” Angel said. Schulman confirmed as much in a phone call with Gawker, saying that the review was “a factual misrepresentation. “It said things about me that are not true, including that I'm transphobic,” she said. “I’ve been a trans ally since the 1980s, and I take that charge extremely seriously. So I wrote to the editor and I said, ‘You know, this is not accurate.’”

In particular, Schulman said, she took issue with Osterweil’s characterization of the Pose example, in which she questioned whether Schulman had sufficiently researched the protest’s attendants (“It’s not as though arrest records historically represent Black trans people’s genders accurately. How does she know? There is no footnote or further evidence offered.”) Schulman said she had confirmed everyone there through footage and interviews. She also cited a line claiming the book argued “that the ACT UP model… is the best way to ‘make change.’”

When the Currents fact checkers reviewed Schulman’s complaints, they found some of the problems she had raised “very compelling on a kind of narrative level,” but none that rose “to the level of factual correction.” In other words: it was a matter of interpretation. “It should be said, a lot of the meat of [Osterweil’s essay] is actually in the analysis,” Angel said, “not in the nitty-gritty facts.”

Rather than issue a correction, they invited Schulman to write a letter to the editor and contest the analysis. She declined, asking instead to “see the fact-checking.” The Currents editors refused. (This is typical: most publications’ ethics guidelines preclude writers or editors from sharing pre-publication drafts with subjects.) Schulman then requested some kind of mediation; one of the editors, who is involved with the National Writers’ Union, suggested reaching out to its affiliate, the Freelance Solidarity Project.

Schulman said her grievance was initially received with sympathy and taken to its committee to discuss possible recourse. They later told her, as she put it, that “there was substantive value to [her] argument, but that the committee was in disagreement about whether or not they could say so.” According to Schulman, the union didn’t “want to be in a position of making factual claims.” (The National Writers’ Union did not respond to Gawker’s request for comment before press time.)

“Now, this is a very bizarre position, because like, let's say the article said I was a member of the Nazi Party,” Schulman argued. “They wouldn't be able to claim that I'm not because they don't want to be in a position of thinking factual claims. So what good are they?”

According to both Schulman and Angel, the union called on Jewish Currents to offer Schulman the opportunity to rebut the arguments. The editors found this baffling — they had already offered that. Schulman found it insufficient:

After [the union representative] said that there was value to my position, but then he said he couldn't say so publicly, that was when I got turned off. Because if you know that something is true, you should be able to say so publicly. Once you can't say publicly what you know to be true, then you're a bureaucrat. And that's just not how we do things. And then they came up with this crazy statement saying I should have the right to a rebuttal. I don't want a rebuttal.

Schulman later elaborated on why she didn’t write a rebuttal:

The reason I didn't write a letter to the editor is that, now it's searchable on the internet that I've been accused of being transphobic — first time ever. And so the only thing that I think can counter that is to have a linked response from the editor, a retraction. Otherwise, my letter to the editor is lost forever.

Notably, Gabriel’s letter to the editor is linked directly below the Osterweil review. When Gawker pointed this out, Schulman said: “I think Kay did a great job, and I don't have anything to add.” As for whether she’d thought about the dispute in the context of Conflict is Not Abuse, Schulman said:

Yeah, I mean, you have to tell the truth and they need to tell the truth. You know, I'm not suing them. I just want a retraction. And you and I have just identified a couple of areas that are factually in question, that are not interpretive.