I recently came across a TikTok in which a moon-eyed Californian claimed that every time she encounters another human being, she immediately envisions them as a tiny, vulnerable baby. She suggested this as a positive technique for moving through the world, with empathy and grace for all beings.

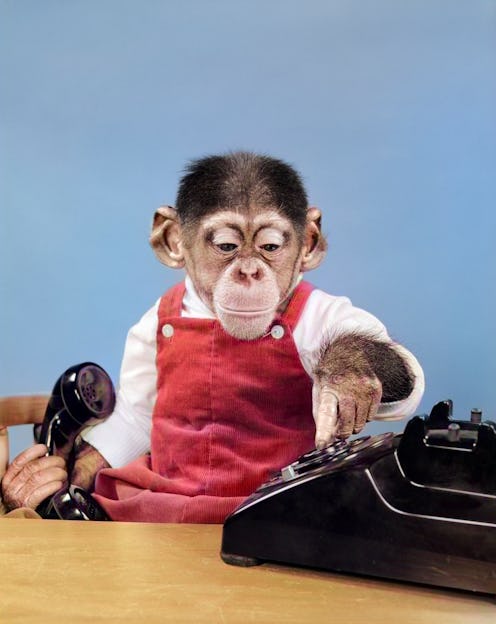

I have developed a similar tic. But instead of viewing those around me as infants, I see every person I come across as — at their core — a monkey. A sophisticated monkey, sure. But definitely a monkey — gripping things with its toes, itching around, gobbling bananas, losing its mind over weird monkey things.

This is, of course, kind of true. We are biological primates, descended from the same ape-y ancestor as modern-day monkeys. We share 98.8% of our DNA with chimpanzees. Oo oo ah ah, etc.

The problem is that we forget this fact all the time. We fancy ourselves such furless sophisticates, so stylish and considered and in control, strolling around upright on our clever hind legs, tapping away with our luxury thumbs at shiny little stones, expressing our higher-order thoughts. I am not a monkey, you say, wiggling your ten-or-so fingers at the screen. I am a human person, in control of my base urges and in possession of refined faculties such as logic and justice and charisma. I have thoughts about things.

You do, you do. But you are also a monkey, my friend. And that is where the difficulty begins.

As our world continues to be flattened into digital space, we interact increasingly not as physical beings descended from apes, but as floaty little avatars and texts. Not as full, flawed humans but as infallible personas or bundles of opinions or, simply, brands.

The result is that we are stupidly divorced from the reality of our imperfect, monkey-like intentions. We expect ourselves and others to be ideologically cohesive and sensible beyond what is humanly, monkey-ly, possibly. We expect a level of logic that is mechanical and obscene. We shiver at the thought of just feeling a way without there being a political, ethical, or rational reason for it.

So when we do just feel a way — especially if that feeling is ugly or petty or stupid or embarrassing — we instinctively attempt to frame it as somehow correct. We are primed by life online to take any base impulse — whether jealousy or annoyance or desire or fear — and assimilate it into the contrived landscape of our publicly-expressed thoughts and opinions.

For example: let’s say a person around your age — a peer, even — reaches extraordinary heights of wealth, fame, and critical acclaim. They are feted the world round. Let’s say you have a certain black hole-esque feeling towards this person. What is this feeling? Surely, it must come from some wrong-doing on this other person’s part: there must be some moral, ethical, or aesthetic crime they committed that has elicited your reaction, because you are a person, and people are principled. Ah, yes, you might think: this person’s output is lowbrow and derivative; it appeals to the lowest common denominator, and that’s why it’s so popular. And not just that — it is reflective of the misguided preferences of the masses, which are formed by the market. Wouldn’t you know it, your frustration is actually at capitalism itself!

Here is where monkey-ism is valuable. You might take a step back and think Yes, I am evolutionarily the most sophisticated mammal there is, capable of creating art and governments and babkas and poetry. But I am also, possibly, a monkey. You might realize that a portion, possibly even a bulk, of what you are feeling is a base monkey emotion: envy. Which is fine, as long as you just admit it to yourself!

Let’s take another example. Let’s say an acquaintance of yours — let’s call her Martha — is simply always traveling. One day Martha’s in Prague, the next she’s in Panama. She stays in inexplicably beautiful hotels and Airbnbs, and she is always tan. Her job — which, by all appearances, takes about 2-3 hours a week — looks to be something to do with “product,” for a tech company whose name has no vowels. Wow. Tech culture is so toxic, isn’t it? And traveling that much is, like, really bad for the environment? And also Airbnb is displacing locals all the time and it’s so fucked up that Martha is contributing to that???

Well. All of that may well be entirely true, but: Hello, monkey. Nice job projecting an (entirely correct, but perhaps irrelevant) intellectual frame onto the plain feeling of irritation at someone who is simply very annoying.

Now, you might wonder, why shouldn’t I be able to raise these entirely legitimate critiques about John’s work or Martha’s travels? Sure, there might be a touch of monkey to my motivations, but air travel and tech and Airbnb landlords are destroying the planet, society, civilization, etc. — and Martha is the perfect encapsulation of all of that, isn’t she?

And herein lies the problem with being driven by our monkey minds to over-intellectualize our envy or annoyance (or jealousy or anger or disgust or simple dislike): it makes raging hypocrites of us all. And it’s a terrible look.

It’s fine to feel basic human emotions, even when they’re ugly. Even when they’re irrational, or trifling, or unfair. What is not fine is the absolute circus around pretending we’re not jealous, or petty, or selective and self-serving in the ways we dole out praise and punishment. The truth is we are not consistent in our principles, and we probably never will be. Welcome to the human condition: we don’t behave like finely-tuned code. We enjoy pleasure and comfort and feeling part of a group. We fear being attacked, being the weakest link, and being left behind.

We are generous and protective and reverent of our friends: when they fuck up, we forgive them; when they mispeak, we hear them out; when they act in utterly poor judgment and taste, we may hold them to account, but we also believe in their ability to do better. We are the opposite with those we dislike. When they fuck up, we ostracize them; when they mispeak, we mock them; when they slip up even a little, we pounce on their shitty judgment as a sign of some greater failing.

(This is not a tirade about cancel culture, though I think we can all agree that both bloodlust — and the perverse pleasure of accusing others of bloodlust — is pure monkey.)

So before deciding that everyone and everything around you is morally bankrupt, complicit in all of the world’s ills, it may be worth taking a moment to look in the mirror and say: I am a primate on a dying planet, a fallible bundle of organs and bones, dressed in fabric and skin, striving for meaning in an unknowable void, attempting to rise above instincts that were encoded into my biology before the time of dinosaurs. I am not a set of coherent ideas and opinions and aesthetics: I am a mess of contradictions, petty and wanting. I may simply be jealous of Sally Rooney.

You can take that mantra for free, if you want it.

I guess what I am saying, in so many words, is that self-honesty, let alone self-respect, requires a willingness to accept that people (namely, YOU and ME) are sloppy, inconsistent, unpolished, unparseable, frequently petty and irrational and unfair — in other words, glaringly primate. It is easy to forget this when we predominantly interact as texts on a screen, our human (monkey) selves mostly obscured. It is easy by design. (And I’m certain interacting as avatars in a virtual Zuckerberg-owned anti-sex dungeon will only make it worse.)

How liberating, then, to remember that we can have incoherent feelings, and can grant others the grace of incoherence, too.

Oo oo, ah ah.

Jennifer Schaffer is a writer in New York. Her essays and criticism have appeared in The Baffler, The Guardian, The Times Literary Supplement, The Paris Review Daily, The White Review, and elsewhere in print and online.