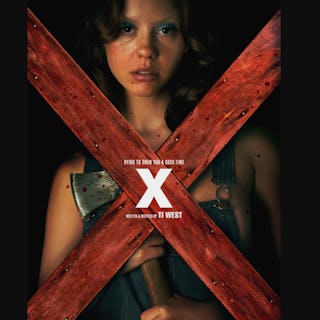

Ti West’s 'X' Is Tasteless Fun

Someone finally doused 'Boogie Nights' in blood

In the opening scene of this year’s Scream, a young cinephile played by Jenna Ortega explains her love of elevated horror — those slickly Kubrickian edifices erected by trauma-mongering A24 auteurs — to a skeptic. “It’s like, scary, but with complex emotional and thematic underpinnings,” she says haughtily. “It’s not just some shlocky cheeseball nonsense with wall-to-wall jump scares.”

The character’s reward for her amateur film analysis is to be stabbed nearly to death. This is surely meant as a sign of witty ambivalence that the film around her is simultaneously satirizing the millennial gentrification of genre cinema and renovating its own valuable intellectual property. It’s the same dualistic shtick being peddled by the creators of February’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre, which, like Scream, functions as a “requel” of its source material — a gesture of revisitation-slash-renewal plotted explicitly around a return to the series’ primal scene and its signature iconography. In these movies — and last year’s spectacularly lousy Halloween Kills — franchise psychopaths and Final Girls get resurrected for reasons somewhere between nostalgic homage and cynical exploitation, all couched in an deliberately imitative style that draws on the visual language of Internet deep fakes. They immerse us in an ersatz past as if retro aesthetics were enough to recapture past glory.

Enter Ti West and his new horror-porno hybrid X — a movie distributed by A24 but mostly non-elevated in its aims. Set in Texas circa 1979, during the widespread evangelicalization of the American West — and the parallel explosion of the adult home video-market — it concerns the efforts of ten-gallon sleaze merchant Wayne (Martin Henderson) to outdo Debbie Does Dallas with a not quite all-star team of exotic dancers, mercenary studs, and student filmmakers. Wayne’s plan is to hunker down in a remote farmhouse whose elderly proprietors don’t know they’re playing host to a film shoot. “This’ll be great for production value,” observes director-for-hire R.J. (Owen Campbell), who tells the cast he’s angling to give the production a little hint of the avant garde in between money shots. They’re into it, and some even offer technical advice. “If you tilt the camera down,” notes Bobbi Lynne (Brittany Snow) while her costar Jackson (Kid Cudi) is filling up their van at the gas station, “it’ll look like he’s using his dick.”

It was only a matter of time before some enterprising filmmaker hit upon the idea of dousing Boogie Nights in blood, and for West — a seminal figure in the so-called “mumblegore” movement of the early 2000s who broke through with the excellent, Satanic Panic-themed thriller The House of the Devil — X represents a return to form as well as to first principles. In broad outline, the film is almost ritualistically predictable: a bunch of shlocky, cheeseball nonsense with wall-to-wall jump scares. But it wears its schlockiness proudly, like a badge of honor, and proves in the process that sometimes, just going through the motions is enough to make for credibly nasty, R-if-not-X-rated entertainment — not to mention a pretty funny commentary on the theme of going through the motions, for pornographers and horror filmmakers alike.

Formally, X peaks with its opening shot, which appears to be a squarish strip of eight-millemeter film until the image starts tracking forward, revealing the borders of the frame as actual, physical walls and resolving in a widescreen composition — a nifty way of suggesting a movie whose meanings will be less narrow than they seem. Clearly chuffed to be working with a real budget, West and his cinematographer Eliot Rocket amuse themselves with complex, predatory camera perspectives, like a virtuoso shot of Wayne’s leading lady Maxine (Mia Goth) cruising nude along the surface of a dirty pond while being lazily pursued by one of its reptilian inhabitants. This landlocked nod to Jaws introduces a note of elemental terror to a scenario closer to the lethal tourist traps of Psycho and, yes, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, which in its original, Tobe Hooper-directed incarnation served as a sort of spiritual sequel to Alfred Hitchcock’s classic — a riff on the myth of Ed Gein and the lethal mysteries of an Old, Weird America.

X represents a return to form as well as to first principles.

Psycho is inevitably name checked onscreen by collegiate boom operator Lorraine — played, coincidentally, by Jenna Ortega — who cites its shape-shifting structure while trying to convince R.J. to let her take part in the shoot. “It starts out as one kind of movie,” she says appreciatively “and then it becomes another one.” Get it? The gradual temptation of good-girl Lorraine in the company of her more sexually experienced collaborators is one of several subplots that West keeps spinning ably throughout X’s first half, which interpserses sequences from the group’s project — poetically entitled The Farmer’s Daughter — with glimpses into the lives of the wizened homesteaders, converging in a strange and affecting sequence in which Maxine sits for a glass of lemonade with the reclusive eighty-something Pearl, who seems to recognize a kindred spirit in the young woman sitting across the table.

The necessary spoiler alert here doesn’t have to do with the film’s story as much as it’s casting, and suffice it to say that this scene shows off Goth’s range in ways that some audience members might miss. The same goes for the film’s second act, which finds Pearl, seemingly in the throes of sundowning, transform from a Peeping Tom into full-on Mrs Bates mode. If a movie as strenuously disreputable as X can be said, even halfway seriously, to have Complex Emotional and Thematic Underpinnings, they’re bound up in a character whose enactment of standard-issue slasher-movie prurience — methodically hunting down and killing the fornicators in her midst — is contextualized by her anguished, alienated relationship to her own sexuality.

A case can be made that scenes featuring Pearl and her husband talking sadly about (and then, spectacularly reigniting) their mutual sex life are constitute a cruel, skeezy form of ageism — call it cronesploitation. But between the central, increasingly less carefully disguised casting gimmick and West’s impressively supple grip on tone — specifically the understanding, that true grotesquerie is funny and disgusting at the same time — X keeps its shit together and pays off nearly every single one of its elaborate set-ups, including Chekhov’s Unloaded Gun, Chekov’s Alligator, and Chekhov’s Fleetwood Mac cover.

During the same mid-film idyll where the characters discuss Psycho, Bobbie Lynne sings a lovely version of “Landslide,” whose lyrics riff on the potentially adulterous energies within the group but also signify cleverly in a different direction. Children get older, and I’m gettin’ older too, she warbles, putting italics around the wistful subtext of a movie that evokes the passing of time as its own form of terror. It’s enough to make you think West has good taste; luckily, the rest of X is working overtime to suggest otherwise.

Adam Nayman is a contributing editor at Cinema Scope and the author of books on Showgirls, the Coen brothers, Paul Thomas Anderson and David Fincher.