‘The Worst Person in the World’ Has an Empty Heart

Despite some dazzling performances, the film is ultimately uninterested in examining life

The hopelessly confused twenty-somethings of filmmakers Joachim Trier and Eskil Vogt’s Olso Trilogy — an informally titled set of films created over two decades — are all too familiar with the trials of being young. In 2005, Reprise introduced two aspiring novelists wrestling with the impossibility of their literary dreams. Six years after, Oslo, August 31st followed an ex-addict struggling to come to terms with an existence that feels bearable only when he’s high. Now a decade later, Trier and Vogt have returned to conclude the Oslo Trilogy with The Worst Person in the World, which stole hearts at Cannes, and garnered two Academy Award nominations. Our lead, ever aimless, is Julie (Renate Reinsve), who may or may not be “the worst person in the world” — we’ll make our conclusion after following her through the film’s twelve novelistic chapters.

How could you not love Julie? At the film’s outset, she’s willful and dreamy. She wants to become everything — unfortunate in a world that demands she settle for something. As we meet her, Julie is already in the midst of changing both careers and hair color. She’s a star medical student, but couldn’t care less about cutting people open. So, Julie tries psychology — and pink hair — but neither is quite right. Finally, our brunette Julie settles upon photography, having always sensed she was a “visual person.” All the while, she fucks most everyone she meets, including Aksel (Anders Danielsen Lie), an artist whose comic books are largely — and suspiciously, we should note — adored by young men. Aksel, who has more than a decade on restless Julie, proposes that they should split. They’re in such different chapters of life, he explains. Instead, Julie falls in love.

Here, in the prologue, is Julie — and the film — at its most exciting. Unfortunately, what follows is less remarkable. This film should technically work: Reinsve is dazzling and irresistible, Lie has never laid himself so bare for a role, and it teems with stunning shots. But rather than thrum with feeling, The Worst Person in the World has an achingly empty heart. It’s not cold, necessarily — just absent.

Julie, actually, is the problem. Although we’re led to believe otherwise, Julie is hardly a fuck-up. She is beautiful, charming, attractive, and men fall at her feet — she is not so much an individual as an archetype. Julie has all the allure of the manic pixie dream girl, but also has politics! She delivers slick retorts to sexist men — older men, no less — with ease. She talks freely about periods and orgasms. Julie has an unerringly confident relationship to her body, her sex, her ideology. Trier and Vogt have the wrong approach to her characterization. They assume that if they force Julie to endure complicated circumstances — break-ups, the death of her ex, and an accidental pregnancy — then Julie might become complicated. But what’s missing is a sense of interiority: how does Julie feel about what happens to her? At one point, Julie tearfully says to Aksel: “Sometimes, I just want to feel.” I, too, wanted to know what Julie felt. Why did she love Aksel? What inspired her art? What did she regret? Did she ever regret? In making Julie so impervious, the filmmakers get away with barely creating a character at all.

Stranger was the presentation of motherhood into The Worst Person in the World. Questioning whether one should become a mother — especially when you’re approaching thirty and have a much older boyfriend like Aksel breathing down your back for children — is an honest reality. But to uncritically present it as a reality that subsumes one’s identity altogether is troubling. For Julie, motherhood is, maybe inadvertently, presented as a mutually exclusive situation — as an either/or with personal artistry. The Julie who fell in love with photography at the film’s beginning becomes an increasingly distinct character from the Julie running away from motherhood — as if to suggest Julie is unable to contemplate both motherhood and her art at once. Only after the concern of motherhood is quelled at the film’s very end does Julie, at long last, return to her camera and artistic calling. But again, Julie is made to be an either/or: she is either dealing with these men, or thinking about her art. There’s a terrible suggestion beneath this: do our filmmakers not believe Julie can weigh both?

They assume that if they force Julie to endure complicated circumstances — break-ups, the death of her ex, and an accidental pregnancy — then Julie might become complicated.

Reprise and Oslo, August 31st, Trier and Vogt’s previous coming-of-age efforts, are also strikingly gendered. “People were also interested back then how [Reprise] is a movie about guys, but they’re not the usual guys you see in movies,” Trier told MUBI Notebook in an interview. Sure enough: in these earlier films, women exist only marginally — not for themselves, but as symbolic casualties of male selfishness, as if the primary function of women’s pain is to remind us of how terrible men are. Women remain symbols in The Worst Person in the World, despite taking on a central role. In this picture, they are either Julie — so ideal as to be effectively symbolic — or entirely nameless, hollowed out by the ordinary cruelty of men. The first such woman we meet is the wife of Aksel’s friend. She is weary — even injures herself — but valiantly takes care of the kids so her husband can spend his free time arguing with Julie about gender equality. Another nameless woman is Julie’s mother, who we never learn about beyond her docility. The mother-daughter relationship is a valuable dimension for thinking about women, but our filmmakers would rather choose to cast mothers as, weirdly, pitiful. All we know about Julie’s mother is that she was abandoned by her husband, and as we learn in a scene illustrating Julie’s family tree, as was her mother, and her mother… and so forth.

Trier continued in the same Notebook interview: “Now people are like, ‘you’re writing about a woman, how can you do that, you’re a man!’” But what makes Julie the other women of The Worst Person in the World failed characters is not that Trier and Vogt are men. It is that they are unthoughtful, and neither seem to be able to conceptualize women beyond their own pity for them. Flimsy phrases like “male privilege” are tossed around with the excitement of an undergraduate who recently encountered it in a textbook. They seem to see women as constitutively burdened by men and patriarchy — as martyrs, of a sort — rather than individuals.. The leading men of Reprise and Oslo, August 31st are afforded the liberty to question their morality, beliefs, and relationships. The leading woman of The Worst Person in the World is only allowed to think about these questions in relation to the anxieties imposed by the men around her: Aksel, handsome rebound Eisvind (Herbert Nordrum), and her asshole father. I wanted Julie to have a life on her own terms — hell, I just wanted Julie to have some female friends.

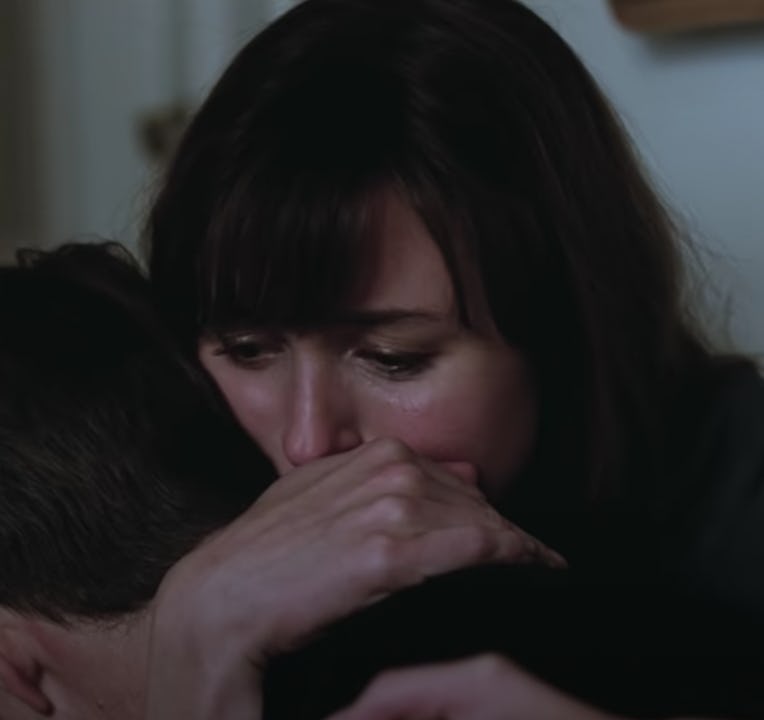

The characterization of women in The Worst Person in the World is representative of a greater shallowness. While touching on the grayer moral questions of life, the film chooses the easy way out each time. As with Aksel’s fate: Aksel, typical jerk and misogynist, claims to understand Julie’s feelings better than she does. In Trier and Vogt’s universe, though, karma is a bitch: Aksel develops aggressive, terminal cancer. In his last days, he confesses to Julie that she was the true love of his life — that all he wants is to be back with her, in the home they once shared. Lie, who is stunning here, shows us a man for what he is: the ultimate loser in love. And for the first time in the film, Reinsve struggles to mirror the weight of this moment, but I don’t blame her. Here is a fascinatingly complicated situation, and — I won’t spoil what happens — a choice that feels ambiguous not out of purpose, but laziness. Aksel might have been terrible, but he was also the man Julie loved. What do we owe to those we loved even when they hurt us? There are magnitudes in this question that Trier and Vogt seem interested in escaping, rather than interrogating.

That’s the fundamental problem: The Worst Person in the World glimpses at many issues — motherhood, family, sexism, relationships, dicks in multiple senses — but never vulnerably examines any of them. What if a story’s greatest achievement is earnest interrogation, even if it means committing to fewer questions? Purpose, love: these are endlessly fascinating questions in themselves — and, also, devastatingly elided in this film. Instead of trying to exhaustively telegraph the commotion of life, Trier and Vogt might have fared better in thinking harder. Halfway through the film, Julie confesses that she has a fetish for half-flaccid dicks. So too, Trier and Vogt assume the viewer will be satisfied by the promise of something more.

Annie Geng is a writer based in New York.