According to The Bookseller, a publishing-industry title based in London, literary agents are currently interested in three things: joyful stories, vampires, and something known as “cozy crime.”

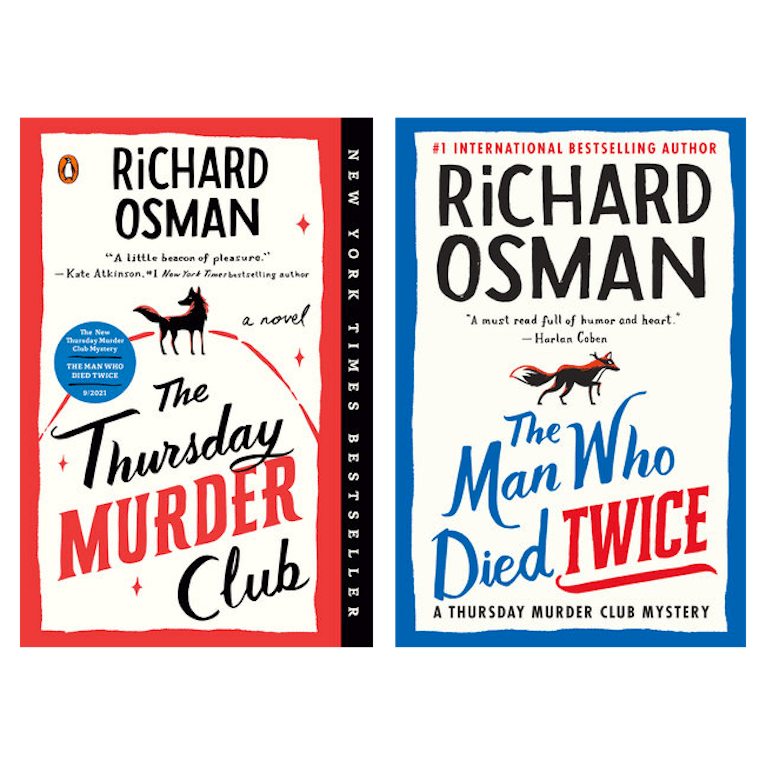

Cozy crime — a loosely defined genre comprising gently humorous, low-stakes novels of murder in provincial settings — experienced a resurgence last autumn, when The Man Who Died Twice, written by English quiz show presenter Richard Osman, became one of the fastest-selling novels since records began (the film rights were quickly snapped up by Steven Spielberg’s production company). The book is part of a series, which follows a diverse group of elderly vigilantes, who call themselves “the Thursday Murder Club,” as they solve crimes and engage in milquetoast banter.

It’s perhaps too idiosyncratically English to become a cultural juggernaut in the U.S., but the series has been well-reviewed on both sides of the Atlantic. The Man Who Died Twice was described in The Washington Post as “funny, moving and suspenseful,” while the Wall Street Journal’s Tom Nolan wrote that it was an “unalloyed delight, full of sharp writing, sudden surprises, heart, comedy, sorrow, and great banter.” Publishing is a derivative industry, and the novel has already inspired a slew of imitators, bearing similar titles, concepts or cover designs, such as Robert Thorogood’s The Marlow Murder Club; Ian Moore’s Death and Croissants, and the forthcoming Murder Before Evensong, written by the UK’s most famous trendy vicar, the Reverand Richard Coles.

This is, I think, the single worst thing that could have happened to crime fiction. These books aren’t just bad — clumsily written and boring — in their own right, they’re entirely at odds with the spirit of the time we’re living through: in England, thanks to a series of corruption scandals, even the most middle-of-the-road liberals are waking up to the fact that the police might not be a benign institution. There could be no better moment for angry, paranoiac, and oppositional crime fiction. Instead, we are offered a wave of novels which tell us that everything is fine.

The Thursday Murder Club books are comic capers, the kind of thing people like to describe as “snort-inducingly funny” and “gloriously silly”; people read them and tweet stuff like ‘Grrr…I’m invoicing Mr. Osman for a bag of Tetley’s, because I spat out my tea on innumerable occasions while reading this marvelous book!” They have been almost unanimously well-received, and come festooned with a host of celebrity endorsements, suggesting that either the UK’s media elite have uniformly bad taste or they’re more concerned with doing their friends a good turn than telling the truth. While allegations have surfaced that Osman’s chart success was partly manipulated — and he has the built-in advantage of being a household name — it’s also true that you don’t sell millions of copies without decent word-of-mouth. People enjoy the series, and I can see why: the books are zippy, fast-paced, and I can appreciate the frequency, if not the quality, of the gags. Such terrible jokes — and in such large portions!

The humor in The Man Who Died Twice generally adheres to a strict pattern, whereby a crime novel trope is paired with an incongruously banal slice of observational humor: “The coffee is Colombian, as was the man who was shot in the vault in the bolt gun that time.” It’s a formula that, after appearing on every second page, begins to lose its capacity to amuse and delight. Practically every gag is some variation of: “It had been a tough day: not only had Mr. Smith been forced to bludgeon a Russian mob boss to death with a hammer, but, even worse, Marks and Spencers had run out of his favorite Victoria sponge-cake!” This brand of humor, the British middle classes tittering fondly at their own reflection, is effectively our version of the Joss Whedon-inflected, soyface banter of the Marvel films, and it acts to the novel’s detriment in a similar way: as the villain points a gun at our heroes in what ought to have been an explosive finale, the tension is deflated with a joke about one of them calmly doing a word search. It feels like someone mugging to the camera in prose, and eventually all we’re left with is a suspense novel without suspense; a mystery novel where the only mystery is why people keep lapping this stuff up.

It’s a uniquely English fantasy of impertinent youth being brought to heel by its elders and betters.

Whatever satirical potency The Man Who Died Twice might have had is dimmed by the fact that each member of the Thursday Murder Club is simply a different flavor of nice: Elizabeth is posh but nice; Ibrahim is fastidious but nice; Joyce is ditzy but nice; Ron is gruff but nice; Bogdan is Polish but nice. In lieu of satire, Osman offers instead the mildest observations imaginable (“all daughters” know how long you should boil herbal tea for) and a set dressing of inane references to cultural ephemera: Bitcoin, Hamilton, the chef Ottelenghi, the YouTube fitness guru Joe Wicks. There is also a recurring bit based on the internet’s most tedious running joke, that ‘69’ is the sex number (if you know, you know…): Joyce unwittingly creates an Instagram account with the username ‘GreatJoy69’ and as result of this is inundated with a stream of direct messages which she doesn’t know how to read. We never learn their contents. Are they supposed to be sexual? Are they just people saying ‘...nice!’? Despite probably being more internet-poisoned than most of Osman’s readers, I couldn’t figure out what the joke was supposed to be.

All of this is as twee as you’d expect. But Osman is an icon of mild-mannered, genial centrism, and what surprised me about the novel is quite how reactionary it is. Going in blind, I could have easily believed it was written by Brexit minister Jacob Rees-Mogg, and I’d guess that its success is at least partly attributable to the way it manages to appeal to the cultural prejudices of smug metropolitan liberals and Little England conservatives alike: one of the secondary characters is a heroic Polish builder (a move described by one critic as “one in the eye for the Brexiteers!”), but he’s also a violent criminal. The novel also exhibits a real disdain towards working-class young people (believe me when I say this is this one of the driving forces of English life.) One of the storylines concerns Ibrahim, a retired Egyptian, being violently mugged by a teenage hoodlum named Ryan, who is less a character and more a collection of cliched class signifiers: KFC, hoodies, skunk, and cheap deodorant. Ryan, we are told, has “been called stupid all his life.” The gang of pensioners swear revenge, using Elizabeth’s contacts as a former MI5 agent to find him, plant drugs in his house, and then send him off to prison (sobbing inconsolably, robbed of even his bravado) for a crime he didn’t commit. It’s a uniquely English fantasy of impertinent youth being brought to heel by its elders and betters: Harry Brown for people who still have the EU flag in their Twitter name. I kept waiting for there to be some volte-face where the gang realizes that revenge is a corrupting pursuit and that maybe this teenager isn’t all bad, but it never comes.

Instead, the gang’s police officer friends cheerfully offer to beat Ryan up:

“Whoever did this, we’ll find them, and we’ll get them in a room with the cameras off and they’ll regret it.”

“That’s my girl,” says Elizabeth. “That’s a proper police officer.”

There’s little sense of moral ambiguity in this exchange, which is presented as charmingly brusque.

We are supposed to like these people, these octogenarian sadists and their twisted vendetta against a vulnerable young man. Osman seems like a well-meaning guy, but it’s at best distasteful to depict boys like Ryan as uncomplicatedly evil and beyond redemption, particularly if your novel is set in a place as unforgiving in its treatment of marginalized young people as Britain. It is, at the very least, tonally jarring. You could argue that I’m reading too much into something that’s only intended to be a light piece of fluff, but Osman himself has said he believes his work to be making a statement about Britain’s class system: “If you want to know what Britain is like,” he told the Sydney Morning Herald last October, “there are many very, very posh state-of-the-nation novels you could read but I do think that The Thursday Murder Club is not a bad place to start. I want people to feel warm and welcomed into the book, but at the end to have also gone ‘oh blimey, we’ve dealt with a few things in there… If I can point out something about the classes in this country, wrapped up in a lovely Agatha Christie-style mystery, then great.” All he manages to say about this subject is that there exists a feral underclass who are rotten to the core and deserve to be locked away at whatever cost.

If the cozy crime genre was limited to Thursday Murder Club, it wouldn’t be so bad, but it’s blossoming into a full-scale cultural phenomenon. There’s Death And Croissants, written by English comedian Ian Moore, which comes billed as “the most hilarious murder mystery since Thursday Murder Club” — a modest claim which may well be true. I spent £3.50 of my own money buying this and then abandoned it early on when the protagonist’s daughter tells him, sassily, “In Facebook terms, dad, you and mum are complicated.” In defense of Osman, he’d at least be savvy enough to fire in a TikTok reference.

All Osman manages to say is that there exists a feral underclass who are rotten to the core and deserve to be locked away at whatever cost.

Hot on its heels is The Marlow Murder Club, authored by TV writer Robert Thorogood. Along with the near-identical title and cover design, it shares with The Thursday Murder Club a posh elderly woman protagonist; in this case one who drinks whiskey, skinny dips, savors the joy of a “fresh pencil,” and exclaims stuff like “sod this for a game of soldiers!” Despite being published by HarperCollins and endorsed by a number of celebrities, it simply doesn’t read like a real book, and features some of the most desultory scene-setting I’ve ever encountered in a work of fiction: “But what Judith loved most about Marlow was the way it was so much more than its picturesque High Street. There was the railway station [...]from which it was possible to get trains to London. There was also a thriving business park on the edges of town that employed thousands of people.” Evocative stuff!

In the spirit of fairness, not every novel billed as “cozy crime” is terrible. There are people doing something similar, but better. Janice Hallet’s The Appeal, told entirely through emails, social media posts and other found texts, is about a fraudulent crowdfunding campaign for a young girl with cancer. Set around an amateur dramatics society in provincial England, it certainly has its cozy elements, but it’s much spikier than The Thursday Murder Club. The milieu depicted is riven with casual cruelty, with the characters snubbing some people and acting with brazen sycophancy towards others. As a satire about snobbery and stultifying social hierarchies, I thought it was pretty good. Antony Horowitz’s Magpie Murders also does something interesting with the genre. The book, set in the present day , contains within it a novella-length pastiche of 1930s detective fiction. It has some almost Scream-esque fun with this conceit, whereby the characters in the present-day section are essentially aware that they’re inside a murdery mystery and attempt to exploit their knowledge of the genre’s conventions. Unlike many of its contemporaries, it actually understands what’s good about the Golden Age fiction to which it’s paying homage. Cozy crime will never be exactly to my taste, but I enjoyed both of these books and wouldn’t balk at either of them being described as “fiendishly clever,” or whatever. The genre can be done well.

Nor do I hold anyone who enjoys the Thursday Murder Club Series in contempt. My own mum, closer to the target audience than I am, described the first one as “a moderately engaging bit of fluff with a few funny moments,” and I do not disdain her, or anyone, for holding this view. It’s not snobbish to expect that popular fiction should be good, and smart, and have something to say about the world. It is, in fact, the opposite. Cozy is exactly the wrong trend at exactly the wrong time. Well over a decade into Conservative rule, Britain is an increasingly cruel and authoritarian place. The last thing we need is a flattering mirror which tells us that deep down we are jolly nice, except for the people who are scum, and that our most prosaic habits — drinking tea, eating biscuits — are endlessly charming.

James Greig writes about culture and society.