The Difficulties of Helen DeWitt

Her new novelette, 'The English Understand Wool,' pits a young writer against the imperatives of modern publishing

In the opening pages of Stendhal’s The Red and the Black, Monsieur Renal, the uncultured, bourgeois mayor of Verrières, is reproached by one of the villagers for the way he cruelly prunes his garden, to which he responds: “I like shade, I have my trees cut so as to give shade, and I do not consider that a tree is made for any other purpose, unless, like the useful walnut, it yields a return.” The only thing that keeps him from cutting down the trees altogether is that he believes no profit can be made from them. This way of thinking, we’re told, is shared by most of the townspeople, who are interested in the beauty of their village only insofar as it attracts visitors who will materially enrich it. But here the narrator breaks in to tell us that although he wishes to give us a portrait of provincial life — “I shall not be so barbarous as to inflict upon you the tedium and all the clever turns of a provincial dialogue.”

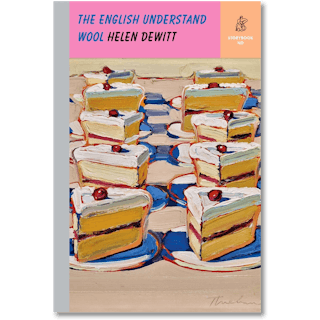

In Helen DeWitt’s new novelette, The English Understand Wool (New Directions), the above passage serves as an epigraph for a different kind of provincial dialogue, this time between an editor at a New York publishing house and a prospective author over the excruciating clauses of a seven-figure book deal. The foregoing image sticks with us: books, of course, are one thing that a felled tree yields. And here, as in Stendhal’s depiction of provincial life, aesthetic value, in the hands of those who cannot recognize it, finds itself at the mercy of market logic. The author in question is the teenage Marguerite, a moneyed girl of the Moroccan haut monde, who has been raised by her decorous French mother to avoid, in all things, mauvais ton (“bad taste”), and the book is an account of her recently scandalized life, after she discovers that her parents are not who they claim to be.

Maman, we’re told, is exigeante, a woman who lives by the dictates of “one doesn’t…” One doesn’t, for instance, ask to be waited on during Ramadan; one doesn’t play the piano in an apartment and disturb one’s neighbors; one goes to Ireland for linen, but has it made up in Paris by a Thai seamstress, and to the Outer Hebrides of Scotland for tweed, which must then be tailored in London, because the English understand wool. All things, in other words, must be handled by those who understand. Language also abides by the same dictates: the English translations of mauvais ton and exigeante suffer from a certain inelegance. And by way of a footnote, we’re shown that the phrase “clever turns” — from the aforementioned epigraph — inadequately captures the connotation of the original, “les ménagement savants,” which means something like “learned handling.”

The opening pages of the story, narrated by Marguerite, are preoccupied with just such details. The text is then interrupted with a note from the editor — why all this stuff about fabrics and French and dinner etiquette? “This seems like a lot of backstory, making the reader wait for the main event,” she tells her. The editor also insists that Marguerite talk about her “feelings” (was she hurt, traumatized, victimized?). Otherwise, “there is nothing to engage the reader and keep them turning the pages.” (Here, one senses a critique of the self-absorption of trauma narratives and their reliance on inflated pathos.) This is not just editorial advice. The publisher wants to tell Marguerite’s story, but the terms of the contract demand that she deliver a manuscript that is “satisfactory” to what the publisher deems to be of interest (i.e. how emotionally fraught her relationship with her parents is). From here, the narrative thread gets tangled in a protracted contractual dispute, and we see the process of trying to rig up a story while also managing the various imperatives that make telling the story impossible.

This no doubt speaks to DeWitt’s own difficulties dealing with the infuriating norms of corporate publishing. The Last Samurai (2000), her debut, which took nearly a decade to publish, was subjected to a ream of “unsolicited advice,” as editors urged her to remove from the novel all the parts concerning algebra, Greek and Japanese language. Instead of rejecting the book outright, DeWitt recalls, they would simply ask her to change the bits they didn’t like (the image of Monsieur Renal rears its head). Anyone who has ever tried to sell a book has had some version of this same experience: the editor loves your work, except they want you to change much of what makes it essentially yours.

DeWitt has described this as “the disempowerment of the author.” It is also the subject of Lee Konstantinou’s forthcoming The Last Samurai Reread (2022), which looks at the novel as an example of the creative and intellectual constraints that exist under capitalism. Publishers feared The Last Samurai tried to do too much and wouldn’t hold readers’ attention. Appropriately enough, one of the questions the novel raises is what can be achieved if one is allowed to commit oneself to several tasks with prolonged focus. Despite the publisher’s lack of confidence in the book, The Last Samurai was a hit (by the standards of literary fiction), selling over 100,000 copies. And yet, the novel fell out of print for nearly a decade, until it was picked up by New Directions in 2016, which has handled DeWitt’s work ever since.

The philistinism of the publishing industry has always been a bit insecure. It knows that it is responsible for a certain amount of culture, and that culture is needed, and so it relies on staid literary fiction by legacy authors to keep face and maintain prestige, while generating the bulk of its revenue from celebrity biographies, kid’s books, and YA. The responsibility of publishing serious work has been largely ceded to small presses (whose good work shouldn’t be overlooked) that are willing to take chances on authors like Ben Lerner and Joshua Cohen, who are then collected by the mainstream and rewarded once they prove successful.

Every now and then a few masterpieces are permitted to slip through. That is, after they receive proper sponsorship. It is only by the grace of good souls like Susan Sontag that American readers even know about writers like Sebald, Bolaño, or Krasznahorkai. Ditto Calvino, whom Gore Vidal helped introduce to the English-speaking world. And Tom McCarthy, whose debut Remainder became a success only after Zadie Smith wrote in the New York Review of Books that the novel represented a path forward for fiction, at which point, the very editors who had previously rejected McCarthy came back with generous advances.

DeWitt penned a send up of such patronage in her story “Climbers,” about a group of writers and their literary agent trying to acquire the work of an obscure Dutch author and market his avant-garde novels to an underread American audience (with the right hype, the agent thinks, one of them could become “the next 2666!”). Sebald and Bolaño were both imported shortly after the millennium as daunting maximalists, as “genius” writers from Europe, where people supposedly take writers more seriously. The way to promote this kind of literature then, has been to fetishize it, by insisting on its “difficulty,” and issuing it as a kind of challenge to the reader. (This was exactly the marketing strategy behind Infinite Jest, which Little, Brown succeeded in turning into a bestseller by daring people to pick it up.)

One of the latent themes of The Last Samurai, which fits into the category of genius novels, is how our culture conditions us to expect very little from what we consume, while also encouraging us to regard expertise as a kind of curiosity. Ludo (the novel’s boy protagonist) may be a genius, or he may simply be an otherwise ordinary child raised in an environment where learning Japanese and reading the Odyssey at age four is considered normal. Perhaps what we take to be genius is simply a term for an anomaly that a market-driven culture, furnished by low expectations, has difficulty understanding and assigning value to.

But capitalism has a genius of its own, and occasionally, it rewards its critics. There is, to be sure, a spirit of satire in this. This is what Charlie Citrine, the protagonist of Humboldt’s Gift, thinks after the unexpected success of his writing suddenly makes him wealthy. The market, he says, is having a laugh: “To make capitalists out of artists was a humorous idea of some depth,” and that it did this “for dark comical reasons of its own.” But to Charlie’s plutocratic brother, Ulick, this is a bridge too far: “I knew the country was headed for trouble” he tells him, “as soon as there began to be big money in art.”

If this was indeed capitalism’s joke on post-war fiction (now beginning to look like something of a golden age), it certainly isn’t funny anymore. Every year there are fewer and fewer readers, admission to English programs dwindles, the publishing duopoly threatens to become a monopoly, and the leviathan that is Amazon is poised to swallow all of it. As a sinking industry yields to such pressures, authors like DeWitt are paradigmatic of those who will be ever-more unlikely to get published.

Fittingly, there is no resolution to The English Understand Wool. After Marguerite outmaneuvers her publisher to ensure that she will receive full payment for the delivery of the manuscript –– regardless of how she tells the story — the editor advises her not to finish the book until the scandal surrounding her parents is resolved, as it will likely alter the course of the narrative. The balance of power has been corrected: the author is unfettered, the editor stays on the botched project mainly to save face, but the story is left untold.

As late capitalism lurches from crisis to crisis, monetizing all activity and extracting value from every nook and cranny of our lives, one of the things it seems to have had trouble assimilating is so-called difficult literature. That is, literature which requires more time, attention and focus than the attention economy would like us to have. And as this economy crowds out more and more of the mental space needed for deep reading, the literature that impedes on this market share is starting to look like something of a refuge.

This is but a new version of an old struggle. The cult of difficulty that we associate with modernism was, among other things, a reaction to the commercialization of literature and the middle-browing of all culture. Difficulty, such as it was for those writers, was a form of protest against their society’s growing estrangement from cultivated reading. It was understood that this would not be a profitable undertaking (Joyce certainly never expected to sell a lot of books). That same struggle, whatever it means today to the people who can still be bothered to read, may actually be the unglamorous out door — if given its chance. But, as Marguerite says, “if you are dealing with people who are blind to bad taste there is no way of knowing.”

Jared Marcel Pollen is a writer living in Prague. His debut novel, Venus&Document, is available now.