EXTERIOR: a beach at midday, the surf shaded by passing clouds; the water reflects the sky so precisely that the shoreline could just as easily be the horizon. The shot, which holds for several beats, is empty of human forms, which is why it’s so unnerving when — after revealing we’re observing the location from the point of view of a young man seated in the sand — the camera suddenly cuts back to observe a trenchcoated figure standing dead center of the frame. How did he get there? The stranger looks upwards as if in a daze — maybe towards the spaceship that deposited him on the ground — before turning and walking slowly in our direction. Gradually, he gets close enough that we can register the expression on his face. It’s empty, unreadable. He keeps coming.

The moment is too placid and enigmatic to qualify as a jump-scare, but it’s nevertheless the perfect overture for a horror movie in which the mind’s eye plays tricks and sinister impulses manifest seemingly out thin air. Cure’s logic is embodied by the wandering, insinuating cipher called Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), whose conversational method is to ask more questions than he answers. “Where is this?” he queries absent-mindedly, over and over. The other man’s answer — Shirasto Beach, outside Tokyo — doesn’t satisfy him, but as Mamiya repeats the words, they begin to take on a mesmerizing, existential quality. Where are we? The question doubles back on us in the audience. What kind of movie is this? And what does this man in the long coat — who claims that he’s going “nowhere” — want from his new friend (or from us) anyway?

When it was released in 1997, Cure was typically lumped in with the contemporary cycle of Japanese thrillers known as J-horror (Ringu came out shortly thereafter), but 25 years later, it stands alone as one of the most unnerving features of its era, and maybe of all time. Where the bulk of J-Horror films deal in supernatural storylines, Cure, directed by Kiyoshi Kurosawa from his own original screenplay, is perched like a bird of prey at the intersection of psychology and sociology. Kurosawa is the great modern filmmaker of contagion, be it chemical, biological, or intellectual; he’s fascinated by how and why things spread, and how outbreaks can, in increments, precipitate a new reality. Or, perhaps, unearth an older one: the rallying cry of Kurosawa’s great, bizarre eco-horror film Charisma (1999), about a tree whose growth portends some coming apocalypse, is “restore the rules of the world.” It’s a mantra that suggests not only the existence of a natural order but also, disturbingly, that we’ve somehow violated its fundamental precepts — progress as an inevitable, potentially irreversible extension of original sin.

With this mind, Cure’s theme is nothing less than free will, and whether it can be expressed in a controlling, consensus-driven community where individual desire is necessarily sublimated to the collective. The film is structured around a series of gory crimes that, depending on how you look at it, are either acts of submission or resistance to Japanese society. The brilliance of Kurosawa’s direction is how it lets us see both perspectives, superimposed over each other at once — a crime scene bloodstain pattern analysis that’s also a thesis paper. This month, Cure arrives on Blu-Ray via Criterion in a extraordinary 4K restoration supervised by cinematographer Tokusho Kikumura that does justice to the uniquely corroded artistry of its visuals; for all the arterial spray spattered in the margins, the film’s images feel as clammy and drained of vitality as a vampire’s victims.

There is surely something vampiric about the pale and mysterious Mamiya, whose victims invite him in by engaging with his seemingly pathological confusion. The ex-psychology student projects vulnerability — he could be the slender, scrawny embodiment of a wandering thought — but he’s actually a master manipulator, subtly incepting instructions in the minds of anybody he encounters. These cryptic incantations prime the listener to commit acts of extreme violence, usually against people close to them; sometime after their meetings with Mamiya, they awaken with blood on their hands, fleeing scenes of incomprehensible violence. The well-liked schoolteacher who meets Mamiya on the beach goes on to sever his wife’s carotid artery; after guiltily trying to kill himself, he tells the detectives assigned to the case that “Devil made him do it.”

It’s a good line, but if, as the old saying goes, all hypnosis is self-hypnosis, then Mamiya didn’t really make him — or any of the other ordinary citizens whose actions render him a serial-killer by proxy — do anything at all. He’s simply a facilitator, or as per the film’s cruelly suggestive title, a kind of self-styled clinician, unlocking a metropolis’ seething, subconscious wants one person at a time. “You wanted to be a surgeon,” he coos soothingly to a female doctor who’s trying to care for him at the hospital, “[but] what you really wanted to do was cut a man open.” Mamiya speaks the truth: his signature, flickering cigarette lighter is a fixation point illuminating the darkness at the center of the human condition.

The sinister mind-controller is a genre trope almost as old as cinema itself: the malevolent criminal syndicate at the center of Louis Feuillade’s epic 1916 serial Les Vampires regularly deploys such tactics to help carry out various thefts, kidnappings and killings (scenes faithfully recreated recently by Olivier Assayas’s wonderful HBO series Irma Vep) The title character of Robert Weine’s German Expressionist landmark The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is a carny cynically exploiting a sideshow performer as his own private somnambulist; the diabolical archetype of Svengali, the singing teacher who telepathically controls his protege, has been inhabited by actors ranging from John Barrymore to Peter O’Toole. No American political thriller ever hit upon an apter metaphorical gimmick than The Manchurian Candidate’s pop Freudian twist of a war hero unwillingly rewired by a duo of duplicitous matriarchs (his own Mom and Mother Russia); the devastating revelation of incest that supercharges Oldboy’s revenge narrative is made possible by similar meddling.

No filmmaker is better at evoking anxiety via blocking and body language.

Given the inherently dreamlike nature of film viewing — the soothing, narcotic ritual of dimming the lights and suspending disbelief until they go up — the hypnosis motif has a lucid, seductive logic that, used effectively, can work on a deeper and more immersive level than a mere plot point. Lars von Trier, whose filmography is rife with controlling, clinical types who get in the ears of vulnerable susceptible victims — from the opening countdown of Europa to the doomed spousal counseling of Antichrist — is such an assiduous practitioner of this mode that a 1997 documentary about his work was dubbed Trance Former; in the climax of his hilariously self-reflexive 1989 horror movie Epidemic (itself just announced for Criterion) a young woman who’s placed into trance before reading a script about the Middle Ages goes so far under that she begins suffering from — and somehow transmitting — the symptoms of Bubonic plague: an outrageous transubstantiation of belief into flesh-and-blood reality.

Von Trier is a provocateur and a showman; what makes Kurosawa’s more measured approach to this particular subject matter so much more frightening is his refusal to stylize his storytelling or imagery too drastically. Shot in drab, desaturated tones against dilapidated backdrops, Cure is oneiric only around the edges. In lieu of elaborate hallucinations, the filmmaker offers up spare, distanced compositions that, like Mamiya’s inexplicable entrance into the narrative, seem to manifest their uncanniness from the inside out. No filmmaker is better at evoking anxiety via blocking and body language, whether in the slow, deliberate movement of bodies across the screen (i.e. the wobbly female apparition in Pulse) or the precise angle of a character’s head tilt.

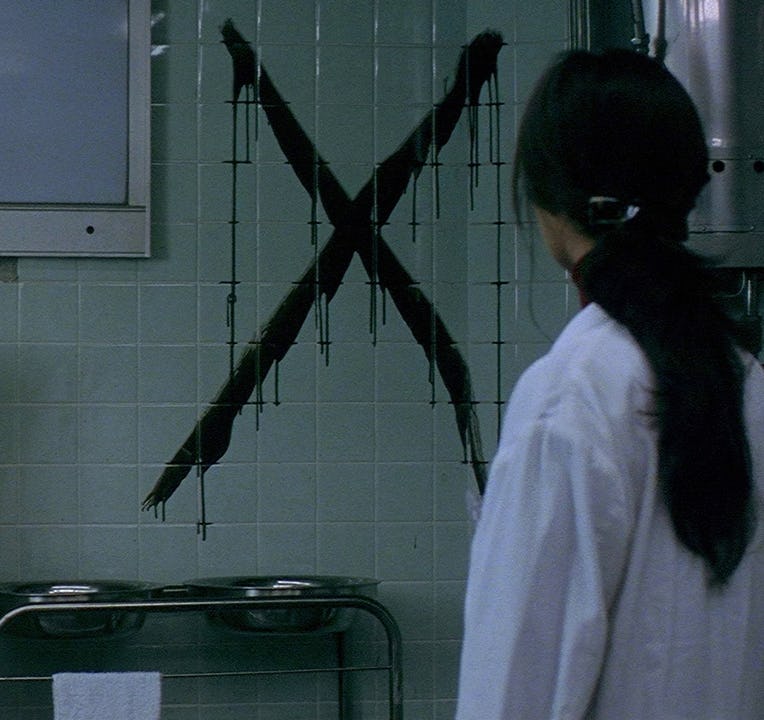

He’s also peerless at using interiors to convey underlying meaning. Evil is in plain sight throughout Cure, mainly in the form of the omnipresent X we see splattered against bathroom tiles and carved into bodies, the metaphysical equivalent of the writing on the wall. Like David Fincher’s Se7en, to which it bears more than a passing relationship, Cure is a procedural, and Kurosawa has Fincher’s same gift for parceling out divine (or demonic) revelation in increments; both directors project their themes directly into the mind’s eye. Cure’s visual language of searching and unveiling, with characters constantly peering through scrims or shrouds — pulling back curtains and peeling away layers — is precisely attuned for a modern fable in which the repressed returns with a vengeance.

Se7en famously ends by quoting and, through Morgan Freeman’s editorializing voiceover, gently correcting Ernest Hemingway’s dictum in For Whom the Bell Tolls that “the world is a fine place and worth fighting for.” A world-weary optimist in noirish cynic’s garb, Freeman’s Detective Somerset agrees only with the second part. But in Cure the dogged and doomed Inspector Takabe (Kōji Yakusho), comes to experience a full philosophical inversion of this sentiment. For Takabe, whose awful, all-consuming job cataloging homicides has had a numbing effect on his physical and emotional health, the world at large is beyond saving, but it’s only through his pursuit, capture and perilous interrogation of Mamiya that he explicitly accepts and internalizes this knowledge, and with it, experiences any sort of lasting peace.

The price for Takabe’s catharsis is the elimination of the long-suffering, mentally ill wife (Anna Nakagawa), whose burden Mamiya relieves him of in the moments before his own death (which, like Kevin Spacey’s John Doe in Se7en, scans unsettlingly as an act of suicide-by-cop, less a defeat than a Pyrrhic victory). This gift from quarry to hunter (or is it the other way around?) only ostensibly keeps Cure from having a happy, restorative ending. The crime that Takabe ultimately commits as a possible act of mercy — whether towards a loved one or towards himself — possesses a charge of ecstatic release, one that carries over into the film’s coda, in which Kurosawa’s powers of suggestion reach an elusive, blood-curdling peak. The penultimate shot, which is the stuff of nightmares, combines visual sleight-of-hand with what can only be called sleight-of-mind. What did we just see? Was there anything to see in the first place? Where are we? What kind of movie is this, anyway?

Adam Nayman is a contributing editor at Cinema Scope and the author of books on Showgirls, the Coen brothers, Paul Thomas Anderson and David Fincher.