'The Black Phone' Review: Read the Story Instead

Joe Hill has a genius for shivery brevity that most adaptations of his work, including the latest, fail to capture

Joe Hill’s 2004 short story “The Black Phone” is a grimly absorbing survivalist drama with a satisfyingly supernatural twist; held captive in a soundproofed basement by a child killer in thrall to his own inscrutable rituals, a thirteen-year old boy uses the room’s broken rotary receiver to commune with the ghost of a previous victim. Once communication has been established, the dead kid offers some practical suggestions about how his successor might escape his predicament.

Like most of Hill’s sharpest work, “The Black Phone” is a limber and invigorating exercise in atmospheric compression, ruthlessly sacrificing exposition — and psychology — on the altar of immediacy. Its wonderfully vicious ending, which offhandedly evokes no less than Hemingway’s old, tolling bell, lands a knockout blow mostly because there’s no fallout, no coda, and no space to exhale. There’s just a punchline, and it’s a haymaker.

Scott Derrickson’s new film version of The Black Phone, co-written by the director and Robert C. Cargill, doesn’t hit as hard, splitting the difference between fidelity and excess and winding up in a sort of no man’s land. The premise is the same, and so is the late ’70s suburban setting — specifically, a dead-end section of Denver, shot in drab, mulchy autumnal tones. Bullied at home by his alcoholic father and also at school by classmates who recognize and resent his soft-eyed sensitivity, Finney (Mason Thames) initially proves helpless in the clutches of The Grabber (Ethan Hawke), who’s already five kidnappings into his reign of terror, luring victims under the guise of a birthday party clown a la the villain of It.

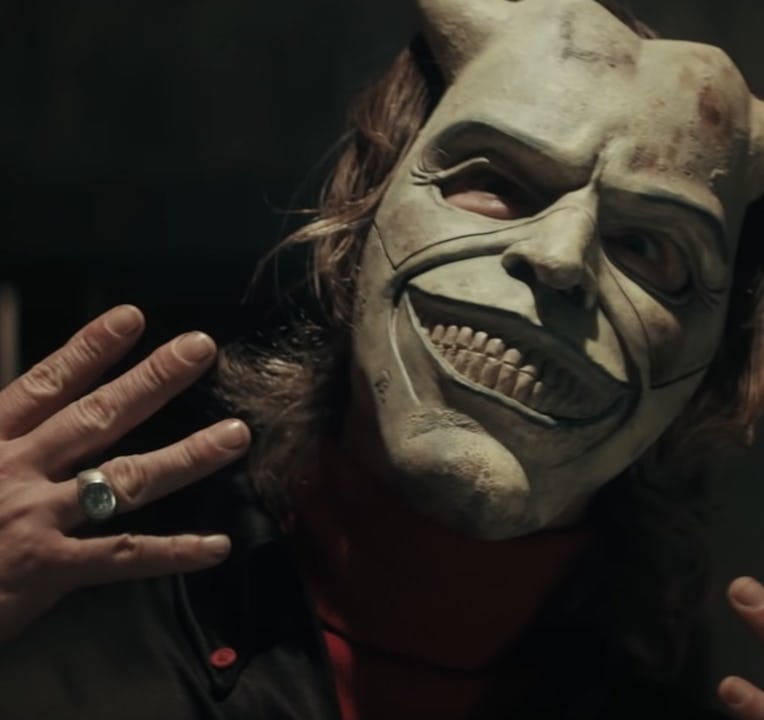

Derrickson and Cargill previously collaborated with Hawke on 2012’s Sinister, an agreeably creepy compendium of millennial genre-movie cliches that earned internet headlines in 2020 after being cited “the scariest movie of all time” in a pseudo-scientific clickbait study that tracked the heart rates of viewers of all ages. (Somewhere, William Castle was smiling). Derrickson, who parlayed Sinister’s success into a gig directing traffic (i.e. the first Dr Strange) for the MCU, is a decent craftsman with a nice sense of pacing; 2014’s Deliver Us From Evil is standard possession-horror stuff with a couple of hellacious jump scares. Some of the changes he’s made to Hill’s material are effective, like reimagining the Grabber from a balding, corpulent thug to a stringy, masked cipher. Playing against both his relaxed, hipster godhead status and the restrictions of a literally faceless role, Hawke etches a memorable portrait of psychic damage. His reedy, sing-song delivery is even weirder than his rictus-grinning headgear; it’s as if he’s trying to sweet-talk himself out of his own psychosis.

Elsewhere, The Black Phone piles on subplots (a psychic little sister), sociological subtext (a sprawling local hierarchy of toxic masculinity), and hackneyed suspense tropes (including a cross-cutting climax lifted shamelessly from The Silence of the Lambs). These additions don’t so much open up Hill’s text as stretch it thin, and finally, to the breaking point. Not even the reliably wonderful James Ransone, cast as a local cokehead sleuth — but dressed up, inexplicably like Ace Ventura — can do much to spark things around the edges. The whole movie is spackled together by a squishy sentimentality masquerading as genuine feeling; by the end, Hill’s nasty, brutish, and short shocker has been cynically reconfigured as a parable of self-actualization, right down to its geeky pre-adolescent protagonist getting the girl as a reward for finally throwing the last punch.

At this point in his career — nearly two decades after the publication of his excellent short story collection 20th Century Ghosts, which included “The Black Phone,” and fifteen years after he publicly confirmed that he was the eldest son of Stephen King, rather than simply his spiritual mass paperback descendant — Hill has become a sort of cottage industry in the field of page-to-screen adaptation. Both the Lovecraft-inflected comic-book series Locke & Key and the vampire fantasy Nos4A2 have been finessed into television series. In 2013, the French director Alexandre Aja made a feature out of the revenge thriller Horns; 2019’s In the Tall Grass, made for Netflix by the skilled Canadian director Vincenzo Natali, is derived from a novella Hill wrote with his dad. That none of the shows or movies made out of Hill’s works have been complete successes so far is less a critique of the source material than testimony to the difficulty of crafting decent genre fare in general. Just ask King, whose cinematic and televisual legacy is so wildly uneven (and who refuses to acknowledge perhaps the one true masterpiece made in his name as anything more than a mean-spirited failure).

It’s probably better, then, that the proposed film adaptation of Hill’s most sustained novel — 2007’s twisty, troubling Heart-Shaped Box, about an aging rock star who buys a haunted funeral suit online and lives to regret it — has been stalled in development hell (the project had been snapped up by Neil Jordan). A carefully measured send-up of rock star largesse that mutates gradually into a chaotic occult romp, Heart-Shaped Box betrays Hill’s familial influence while also staking out its own generational territory. By dividing the narrative into chapters pointedly named for both Boomer rock and ’90s alt staples — AC/DC and Nine Inch Nails; Led Zeppelin and Pearl Jam — the author positions himself as a bridging figure. Heart Shaped Box’s protagonist, Judas Coyne, is an older man wrestling with a long legacy of pop-cultural shock tactics, alternately exulting in and trying to remove their residue; what better theme for the reluctant, self-effacing heir to the throne of American literary horror than the ambivalent compulsion to amass artifacts that testify to their own demonic authenticity?

If Heart-Shaped Box is Hill’s most fully realized longform work, his greatest gift — on display throughout 20th Century Ghosts — is a knack for shivery brevity. In addition to “The Black Phone,” the collection includes a pair of miniature masterpieces that cover a surprisingly broad patch of tonal terrain, from the grotesque goofiness of lead entry “Best New Horror,” to the elegiac lament of the eponymous “20th Century Ghost.” In the latter, a teenager encounters an apparition at his local movie house, whose name, The Rosebud, conjures up not only a history of cinema but also a more ephemeral sense of loss. In one exquisitely measured passage, the hero’s excitement at having a pretty girl whisper to him during an afternoon matinee is offset when he notices her nosebleed — a minor injury that serves as a hairline fracture in an otherwise blissful and ambiguous moment of unreality (and, inevitably, explodes into a gory torrent a few sentences later). The impression the story leaves is one of surpassing tenderness — a soft spot for old things and the traces they leave behind.

At the other end of the spectrum — and in the first rank of Hill’s output — lies “Best New Horror,” a title whose wry self-reflexivity drops a gauntlet in the lap of the reader; here, it promises, is a story you haven’t heard before. The joke of “Best New Horror” is that its narrator, one Eddie Carroll, has heard — and read, and edited, and published — it all before; he’s the jaded curator of a celebrated anthology series whose life’s work shepherding genre fiction good, bad, and ugly into the public eye amounts to “thousands of hours he could never have back.” When it comes to scary short stories, then, Eddie is a very reliable narrator, but we don’t have to take his word for it that. “Buttonboy”— a tale of abduction and physical and psychological torture with distinct (and probably deliberate) echoes of “The Black Phone” — is awful stuff; the precis we’re granted through Eddie’s eyes is disturbing in a way that discombobulates his (and our) responses and sets him on a path to contacting its author, against the warnings of literally everybody else in his orbit.

What Eddie is after in “Best New Horror” is an explanation of where a story as unsettling as “Buttonboy” — a “flower of unspeakable beauty,” he calls it, in what may or may not be a nod to Baudelaire — comes from; whether it’s truly possible for an artist to invent a set of such misanthropic details, or possibly channel them from their own reality (or beyond). It doesn’t matter that the outcome of Eddie’s quest is so predictable when the details of his journey, which takes the form of a sort of traveling atrocity exhibition located deep in the Old Weird America, are so outrageously funny, or when the alignment between ecstatic revelation and O. Henry-ish comeuppance is so delightfully airtight. Like “The Black Phone,” “Best New Horror” ends on a darkly comic note, one that somehow leaves nothing and everything to our mind’s eye. If Hill never quite topped it, that only testifies to how high he set his own bar; if nobody ever tries to adapt it, that’s because — like all the best horror fiction, new or otherwise — it’s unimaginable in any other form.

Adam Nayman is a contributing editor at Cinema Scope and the author of books on Showgirls, the Coen brothers, Paul Thomas Anderson and David Fincher.