Over the weekend, at least eight people were killed at Travis Scott’s Astroworld festival in Harris County, Texas, in a mass scrum of people rushing the stage for the rapper’s set. Many people were trampled; some of the passed-out bodies were crowd-surfed away from danger. According to the New York Times, though, the festival’s medical personnel were “overwhelm[ed]” by “the number of people who needed care” even before Scott’s got onstage. ParaDoc, the company that prepared the festival’s medical response plan, claims that isn’t true and actually the problems only started happening once the surge began. An executive for Harris County, which owns the venue where the show took place, told the Los Angeles Times that the event’s security plan, prepared by an Austin, TX company called ScoreMore, was “vague.” A nine-year-old boy is in the hospital with a swollen brain. “There’s families, all of these people wanting answers: the community, the country. And they deserve them,” the Harris County executive told the L.A. Times.

To be fair, ScoreMore’s plan, a draft of which was published by CNN this week, is actually quite specific in parts. Unfortunately, those parts are often the ones detailing how to respond to incidents based on the degree to which they “pose [...] a risk of liability.” Elsewhere, the plan pledges that “crowd management techniques will be employed to identify potentially dangerous crowd behavior.” What those techniques actually are is never mentioned, but the plan advises personnel to “not engage the crowd” if it’s “exhibiting threatening or destructive behavior.”

This is certainly not Travis Scott’s fault, even if before his set, Houston’s Chief of Police visited the artist’s trailer and, per the New York Times, “conveyed concerns about the energy of the crowd.” It’s not clear to me what this anecdote is supposed to imply, beyond that it happened. Are we supposed to think that Scott… Ignored him? Maliciously rapped on a stage with the intent of causing a mass casualty event? Refused to believe that the Houston Chief of Police was a psychic and could tell something bad was going to happen? “The idea that the promoter and the artist have more power than the police, more power than the fire marshal to control the safety of the crowd, are you kidding me? That’s a joke,” a crowd-management specialist told VICE.

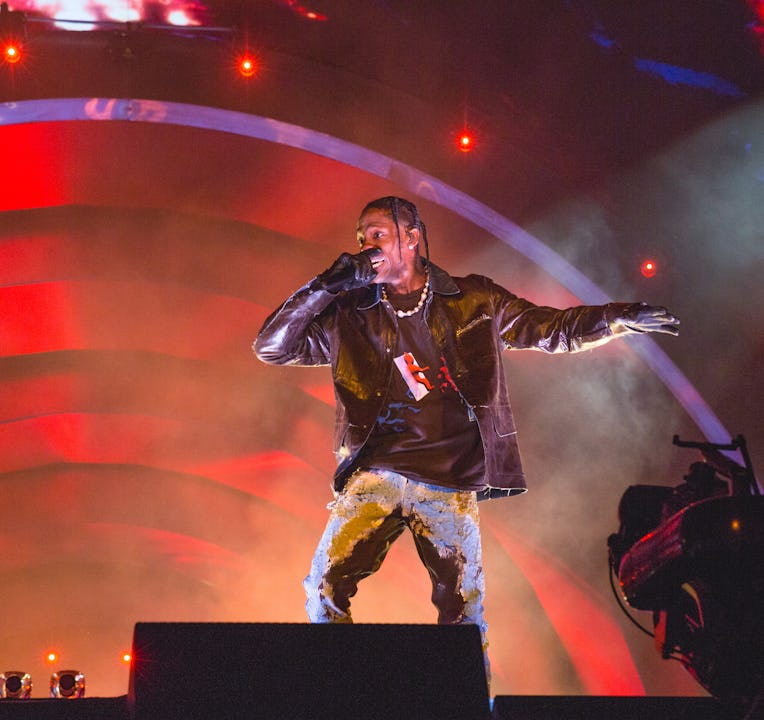

Yes, Scott got onstage and encouraged his fans to “rage,” and yes, he didn’t stop his set while people were dying, but he was also performing to thousands of people and had a light show going that would have made it hard to actually see anything specific within the crowd. It seems like to the extent that he was aware that something was happening, he tried to help as best he could. But Travis Scott does not have magical powers to start a riot. He is popular because his music embodies the sort of rowdy nihilism that young people have felt across decades. It’s the same reason young people have always been drawn to things like punk and screamo and rap-rock and death metal and hardcore hip-hop and mosh pits and going to Warped Tour and speeding and drinking in fields until they throw up. I once knew a kid who wrote quotes from Fight Club on his bedroom walls, y’know?

If part of the fun of an event like Astroworld is the possibility of going buck wild, it stands to reason that the people running that festival could have opted for a strategy other than “doing nothing and then stopping the event because it has devolved into chaos.” A blog post by an Australian security service notes that security people can focus on checking the crowd for people who may need help — whether they’re injured, dehydrated, or just seem like they’re having a bad time in the middle of a mosh pit — and ushering them to safety. The idea being that if you contain the crazy in one area, rather than letting it fester in pockets within a greater whole, everybody has a good time while maintaining their preferred level of intensity. Maybe they could have tried that?

What has gone mostly unspoken regarding the Astroworld incident is that its organizers at Live Nation have spent the past decade consolidating their grip over the concert industry, to the point that they’re really the only game in town. There’s no competitor out there increasing its safety standards and forcing Live Nation to follow them (or vice versa) in order to not appear willfully negligent, which also leaves government regulators only able to compare Live Nation to itself. Instead of someone pushing Live Nation to proactively create the absolute safest environment it can, the company, as noted in its annual SEC report, takes out insurance policies and sets aside money to cover itself in the case of a serious issue at a show or a wrongful death/personal injury suit. Reading through its annual report, you would be excused for getting the impression that Live Nation treats injury and death at its events as “liabilities” in the most removed sense of the term, no different from an absent beer vendor or a rained-out show. Given how Live Nation essentially bakes tragedy into its accounting spreadsheets, it will probably not be truly punished because of what happened.

If you look at festival fiascos such as the complete societal collapse that was Woodstock ’99, the druggy violence characterizing 1969’s Altamont Free Concert, or any number of lesser-known incidents, you can pick up on a certain pattern. First, you’ll find that the people who organized the event ended up cutting corners in ways that both leave them unprepared for an outlier event resulting in an emergency while creating the conditions for some outlier event. Woodstock ’99 was held at a decommissioned military base in the middle of the summer, full of heat-amplifying concrete, not enough water, and too many people from MTV; the folks who set up Altamont decided to get the Hells Angels to run security in exchange for free beer.

After the tragedy itself comes an urge to point to it as evidence of a greater social failure, be it the greed of the late ’90s or the looming death of the hippie movement. So far, I worry that Astroworld will end up serving as some incoherent parable for why aggressive music is evil and drives children to madness. Some people are already reviving a literal Satanic Panic to explain what happened. This is obviously silly, but also a distraction from the more important question of why we allow one company to maintain a monopoly on concert promotion and how concert safety plans are ever allowed to be vague. There’s no devil here, except the one that lives in the details.

Drew Millard has written for The New York Times, Vice, The New Republic, and The Outline and is currently working on a book about golf.