I know we live in the era of everything, but it’s hard for me to find new music these days. Not all the new stuff is bad, not all the old stuff is good, and vice versa, but the importance of music, the engagement with it, at least on the intimate and personal level, to me, feels a little too quick lately. Yes, I am saying I miss the “real” stuff, the handwritten playlists and scratched discs traded back and forth, plus the odd corrupted torrent file. I’ve been using an iPod since I was 12 (Classic, now back to Touch because of the storage capacity, though I still have my original, plus a backup because iPod purists like me are really undiagnosed hoarders), with a kind of “separate devices for separate tasks” ethos. If I’m being honest, these days it’s also a way of not using my phone. But lately it means that, rather than scouring the internet for what’s fresh, I’ve been going back to all the music I only half-listened to or outright skipped when I was growing up, the stuff that’s lived in my library for years, the nameless files, the large catalog of songs under Unknown Artist, plus the stuff my parents listened to.

This is how I found my way back to Siouxsie and the Banshees.

My favorite Siouxsie and the Banshees story — likely apocryphal — is when they played their first ever live show in 1976 with an improvised rendition of the “Our Father” prayer, which tickles a lapsed Catholic like me (as far as I can tell, a recording of this set doesn’t exist, though the band would lay down a 14-minute studio version for the 1979 album Join Hands).

The band was filling in for a group that had dropped out of the 100 Club Punk Special, a two-day festival at the famed 100 Club in London. It was Siouxsie Sioux (real name Susan Janet Ballion) and bass player Steven Severin, the band’s founders, with a couple one-time musicians to fill it out: guitarist Marco Pirroni, who went on to play with Sinead O’Connor and Adam Ant, and 18-year-old John Simon Ritchie (soon to be immortalized as Sid Vicious of the Sex Pistols, but he wasn’t in that band yet; however, he was already a little shit: during the festival, he apparently threw a beer glass during a performance by the Damned, which shattered and blinded a girl in one eye) on drums.

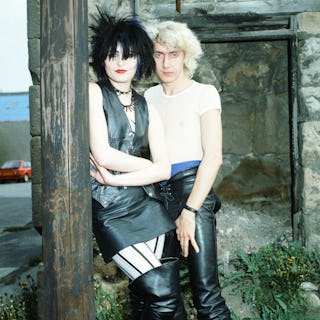

By this point, Sioux, Severin, and a group of other teenagers and young adults, including Billy Idol, had been following the Sex Pistols around England. Journalist Caroline Coon called them the “Bromley Contingent” in an effort to draw a unifying aesthetic ring around the growing punk movement. It is impossible to overstate the profound effect Sioux had on club and punk fashion, with her jet black hair, leather harnesses, cat-eye makeup, and red lipstick that has now become a kind of goth visual shorthand. But it almost seems as if Siouxsie and the Banshees, the band, came out of nowhere.

I’ve been hearing Siouxsie and the Banshees intermittently my whole life, most of my early familiarity relegated to “Cities in Dust” and the band’s name. I say hearing, not listening, because I wasn’t choosing to put them on, they were just around, part of the general, hand-waving ‘80s music I associated with my mom, who would avoid the darker stuff but play the pop-friendly radio cuts (in general, her taste skewed towards Depeche Mode and Sade).What I had been listening to — Radiohead, The Smiths, Joy Division, LCD Soundsystem, The Red Hot Chili Peppers — seemed divorced from any kind of musical lineage, the way most things you discover as a kid do. Of course, all these bands and more have talked about their love for Siouxsie and the Banshees, the innumerable ways seminal records like Kaleidoscope and Juju influenced their sound.

Going back to the source isn’t always rewarding, especially if subconscious preferences for cleaner, more modern production techniques or less meandering albums undergird your expectations. And, where certain eras like the late ‘70s and early ‘80s are concerned, it can be a minefield of corporatized fashions and insincere gestures toward some sort of pretentious, higher level of musical consciousness (“this is the real thing!!!”), which is an admittedly easy trap to fall into. But there really is no one like Siouxsie and the Banshees, and I mean that in a slightly obsessive way.

It’s been a long time coming, but my way into the band finally arrived late last year, after listening to Juju’s “Spellbound” and “Monitor” on repeat, when I had the realization that Siouxsie and the Banshees is a drummer’s band. The shadow of guitarist John McGeoch, whose distinctive style can be heard on Kaleidoscope, Juju, and A Kiss in the Dreamhouse, is long. Really, when musicians like John Fruiscante of the Red Hot Chili Peppers or Ed O’Brien of Radiohead talk about why they love Siouxsie and the Banshees, they’re talking about McGeoch. And if it’s not about McGeoch, it’s about Siouxsie Sioux’s voice, resonant, full-throated, prophetic, the kind that stops traffic. But McGeoch’s playing and Sioux’s pipes shine because of the rhythm they’re performing to, one that, contrary to the roughness and chaos of early British punk bands, was polished and honed through professional musicianship.

Like The Police or The Clash, Siouxsie and the Banshees’ sound is propelled by and punctuated with the kind of percussive inventiveness, courtesy of Peter Edward Clarke (better known as Budgie), that is hard to describe if you’re not also a drummer. It’s also hard to stress how rare it is for the drummers of mainstream bands to be at all interesting, often because they don’t have much room to be original. It’s not complicated fills or showy solos or huge drum sets or even odd sounds. There’s a personality that comes from how hard a drummer hits, how their drums are recorded, what patterns they’re drawn to. Budgie favored tom-tom and hi-hat repetitions that, at times, tip into the kind of neverending rhythmic loops you’d hear from a drum circle. But his distinctiveness, complimented by that of the other band members, changes from album to album, just like the band.

Casual listeners of Siouxsie and the Banshees tend to gravitate toward the albums with the most recognizable singles: Juju because of “Spellbound,” Tinderbox because of “Cities in Dust,” the odd compilation that features the band’s debut single “Hong Kong Garden,” which never actually appeared on a studio album. Holistically — or, if you’re streaming, algorithmically — this is an interesting conundrum because most of the time, a Siouxsie and the Banshees album sounds insanely different from a Siouxsie and the Banshees single. The songs can be long, like most from Tinderbox, or willfully circular, like most of A Kiss in the Dreamhouse, or genuinely scary, like pretty much all of Hyaena.

Each album builds off a base of lyrical preoccupations and instrumental sounds, but the directions they go in are hard to predict and sometimes off-putting. Plus, few groups have as distinctive and sometimes offensive a visual language as Siouxsie and the Banshees, goth and punk and glam and ill-conceived provocation, that conjures monolithic associations the same way Nine Inch Nails does. For someone interested in placing Siouxsie and the Banshees in the pantheon of formative ‘80s bands, songs like “Arabian Knights” and “Happy House” offer a general glimpse, while also giving you a fair idea of the band’s median style. For someone interested in music they can sit with and continue to return to over months and years, music that’s both danceable and brooding, profound and subterranean, the band’s entire discography is extremely rewarding.

I needed more time than I thought I would between Siouxsie records, just to savor the sound and, in a piecemeal way, attempt to construct a context for where each album appeared in time. Thatcher, synth pop, Iran and Iraq, new wave, the Iron Curtain. More than most bands, they communicate a landscape of chaos and upheaval that feels timeless, but is quite specific to its time. You miss that stuff, the opportunity for art to resonate deeply beyond the soundtrack of life, when you surrender your musical curiosity to an algorithm. But I’ll step down from my pedestal now and say that, when you’re ready, the album Kaleidoscope is where you should start.

Nicholas Russell is a writer from Las Vegas. His work has been featured in The Believer, Defector, Reverse Shot, Vulture, The Guardian, NPR Music, and The Point, among other publications.