It’s easier than it should be for individuals, or individual things, to make their mark out here in the desert. Large Western states like Nevada inspire the kind of romanticism and uncritical fondness that has the appearance of overcompensation. It’s either that or you just give up trying to describe what it’s like to live here, as I have. Insert hotel joke, insert temperature comment, insert Hangover reference. You can waste a lot of time doing this. The only Vegas-specific cultural item that’s continued to mean something to me into adulthood is the the band the Killers, whom I still like. Let’s get that out of the way. I love the Killers, shut up. They illustrate all the misconceptions of what it “really” means to be from here, subvert them with broad brushstroke anecdotes and observations about the crumbling establishments and city spirit of old, then lean into a misconception locals can buy into.

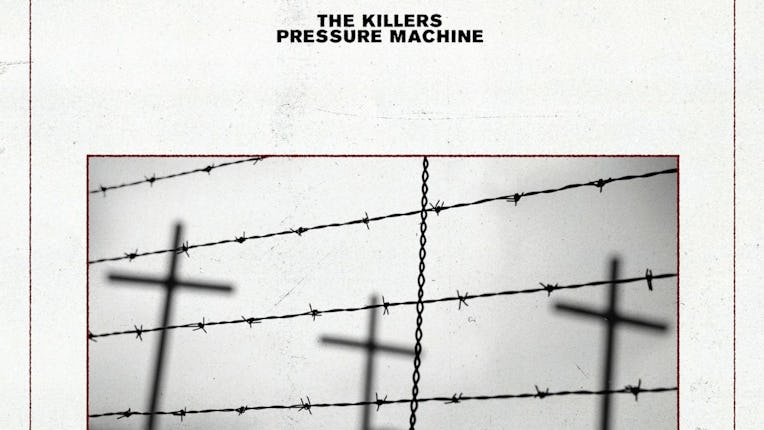

Last year, I wrote about the mythology that the Killers traffic in, this unrelenting and earnest vision of Las Vegas and the frontier and the desert and the people in it as misunderstood, as fickle and downtrodden, as everlasting and worth telling stories about. I still agree with that assessment but I think, with the release of their newest album Pressure Machine, I’ve at least come to better understand what The Killers like, do.

That Wild West thing, that Saturday night versus Sunday morning thing. Frontman Brandon Flowers can’t get enough of this swaggering Americana because, more than his embrace of Mormonism or his vaguely liberal posturing or his nostalgia for the early aughts, he fancies himself a Vegas local. And locals here are some of the cheesiest people alive. Whatever, he doesn’t even go here anymore, so I’ll call him a desert local. The point really is that there are real problems facing the people who call this place home and the best he can manage is something bald-faced and inelegant like “When we first heard opioid stories, they were always in whispering tones / Now banners of sorrow mark the front steps of childhood homes.”

Flowers has long wanted to be Latter-Day Springsteen, but on Pressure Machine that simply amounts to apologia for the white working class. Instead of another record ruminating on what it means to be from or live in or tell people about being from Vegas, Flowers turns back towards Utah, to the little town of Nephi where he spent a good chunk of his childhood. Each song acts as a self-contained story, told from the perspective of a Utahn (a Nephiin?) who faces the pedestrian struggles of all hard-working Americans. Small town malaise, “hillbilly heroin pills,” marriage to the nearest available bachelor, passed-down legends about the railroad. Here, electric guitars and bombastic choruses, Killers staples, are less centerpieces than accents. Pressure Machine has more of the feeling of a down-to-your-roots record, like Miley Cyrus after she decided she was done being black. It’s got a blaring harmonica on “Quiet Town,” acoustic guitars on most every track, Phoebe Bridgers on “Runaway Horses,” more shoutouts to the destructiveness of opioids. This is Nephi, Flowers seems to say. Well, Nephi as he remembers it.

Wait, wait, but haven’t the Killers always been doing this? No one actually believes the shit they say about Vegas or the capital-W West, right? Yes and no. The difference between Pressure Machine and, say, its fraternal twin Sam’s Town is the introduction of a supposed realness or raw quality. To this effect, Flowers and co. solicited the services of the crew behind This American Life to source interviews with actual residents of Nephi for use as song-openers throughout the album. I rolled my eyes when I first learned this, but these audio clips offer up the tantalizing possibility that the true dream of a rock star is to go into podcasting.

There’s a poignancy that does feel true in the variety of clips and their sometimes clashing viewpoints. Some residents seem content to stay in Nephi forever. Others feel crushed by their inability to leave. Even Flowers fancied himself an outsider when he was living there, according to the band’s splashy cover story in NME.

This is standard small town stuff and I know a large number of my high-school classmates felt similarly. But getting at the juicy, revelatory bits of what it means to live in a place needs something more. So often, civic pride means settling for really terrible slogans and supporting sports teams that never make it to the prelims. Which can make it easier to latch onto things that seem to reflect something bigger, whether that’s more noble or more hard done by. That Flowers hews so often to flattery can seem a bit like pity. I’m sure the residents of Nephi find all this amusing, maybe even a little gratifying. Lord knows, Flowers has spent enough time in the media lately talking about his still very current connection to the town. But the way he paints the people who live there, Nephites seem like so much window dressing. They don’t change, they can’t control their lives, and their problems, much like the miracles they talk about, seem to come from nowhere, all-consuming but ethereal.

It’s hard to take charge of your story, even more so when you have world-famous rock stars who don’t even go there making you famous. I grew up with the Killers as a lightning rod of cool, maybe the only export from Vegas that wasn’t mentioned with a snort unless you talked to someone with a gambling addiction or a corporate hack who loves going to conferences. The fact that, for a while, everyone was convinced they were British was a big reason why it seemed like they were putting a different spin on things round here. They didn’t sound like they were from Vegas.

Of course, over the years, there’s been a lot of retconning in the media about this. Their “neon” music, their rebellious spirit, blah blah blah. It’s part of the packaging by now. Pressure Machine as an album is actually really good. The music is, anyway. Lyrically, Flowers does what he does best, which is turn everything into a parable celebrating white diversity. No, I don’t want the Killers to write more inclusive music factoring in the stories of people like me. Yikes, dude. They’re just at their best when they don’t take themselves so seriously.

Nicholas Russell is a writer from Las Vegas. His work has been featured in The Believer, Defector, Reverse Shot, Vulture, The Guardian, NPR Music, and The Point, among other publications.