Of Course Disney Released a Sex Pistols Show

Danny Boyle's new miniseries isn't good, but it is revealing

Given the dire state of things, a miniseries about the Sex Pistols, even directed by arch-nostalgist Danny Boyle, isn’t a particularly offensive proposition. There have been several treatments of the group already, including the 1986 Sid and Nancy, featuring Gary Oldman at the peak of his chaotic early style, as well as 1980’s The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle, featuring the members of the band themselves. And with ready source material in guitarist Steve Jones’s memoirs, 2017’s Lonely Boy: Tales from a Sex Pistol, it’s not surprising that the adaptation industrial complex has finally scooped the storied outfit up.

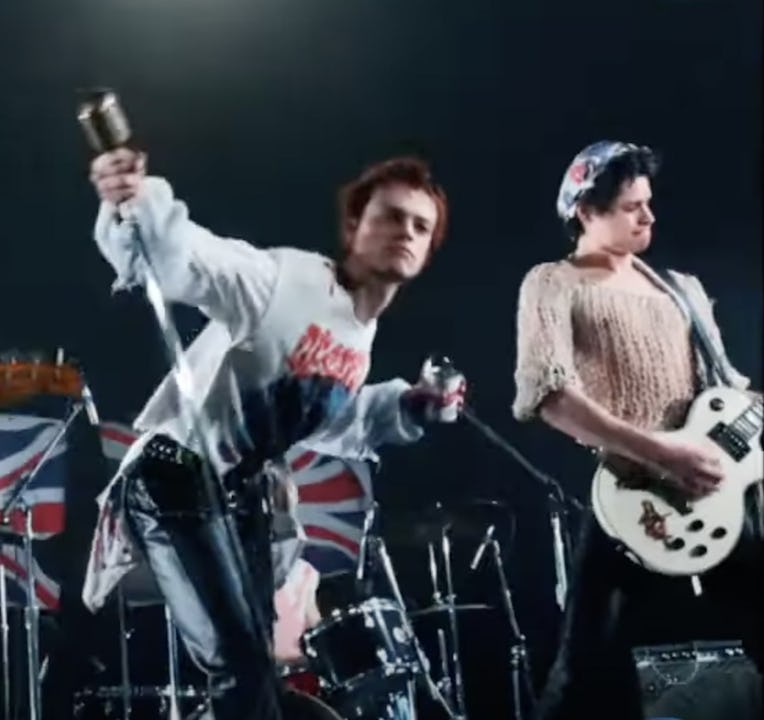

It’s also not surprising that the show is not very good. Thoroughly predictable in both form and content, Pistol, a six-part series streaming on Hulu in America and Disney+ in the UK, is a mélange of digital grain and pointedly lopsided camera angles, while its beautiful cast of caricatures alternates with vertiginous speed between shopworn sneering and maudlin vulnerability. The cynicism of the narrative is breathtaking: the early episodes focus on Jones’s youthful life of crime and his flowering as a punk rock archetype under the protection and guidance of Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren, a role Thomas Brodie-Sangster plays as though he were drunk and asked to do his best Malcolm McLaren impression. Jones’s bouts of stage fright are explained by cutaways to horrific depictions of his sexual abuse by his step-father. That these scenes are a half-step short of Gaspar Noé is probably an attempt at boldness and daring, rather than the complicity it comes across as. The later episodes, when they’re not embroiled in the clichés of runaway success, exploit the swift deterioration of Sid Vicious with all the verve of its original manufacturers. The basic competence of Pistol — Boyle is undeniably a pro — makes it all worse, not better; this was done on purpose.

Reviews have tended to focus on the pretty, talented cast and the formulaic narrative. Elsewhere, the reception is as varied as it is of everything, ranging from a small fandom to haters as repulsed as I am. This latter group seems split into basically two factions: first are devotees of the band, who find PISTOL a glossy desecration of the punk pioneers. Second are the snobs, who say that the Sex Pistols were a bad punk band, and that we should all listen to Crass, instead. Sound advice, and both have something to them, but all make the mistake of assuming that the Sex Pistols were a punk band, and not something else entirely. If they were, then the show would be basically correct in its narrative arc: From humble beginnings, a scrappy group is taken under the wing of an enterprising and idealistic manager and emerges as a potent symbol of youthful exuberance in the face of an ossified establishment, only to be swallowed up by its own voracious appetites for fame, for drugs, even, in a pinch, for freedom. A failure, in other words, if a moving one.

But the Sex Pistols were not a failure. The life and, more importantly, afterlife of the Sex Pistols is an unmitigated success, and not only or even primarily in the “underground”: the band is a cultural object so perfectly attuned to its time as to occupy several apparently distinct strata of identity and discourse without contradiction, without blinking, but only rolling its eyes. Nevermind the Bollocks, Here’s…, their only album, reached number one on the UK charts upon release, and has since been certified platinum. In the intervening decades, John Lydon, formerly Rotten, has become a cultural icon, directing his trademark vitriol at audiences and talk show hosts with comforting reliability, most recently against Pistol and Danny Boyle, who neglected to hire the former front man as a consultant. Meanwhile, the band’s frenzied aesthetic principles have made their way into every corner of cultural life, from catwalks to car commercials. It’s called punk, although from its inception punk has been varied in its sound and look. The safety pins, the torn jeans, the spiky hair: the widespread recognition of these and other markers of nonconformity is due in no small part to the Sex Pistols.

To take it from Pistol, you would think that Malcolm McLaren invented youth culture.

In this way, there was nothing new about the emergence of the band as a flashpoint for youth subculture in the UK. Throughout the post-war period, various trends and styles congealed as forms of affiliation for the disaffected working-class young people who listened to American music and disdained bombed-out, austerity-minded homegrown society. Clear tendencies emerged as mods and rockers staked out their cultural territories, which in turn led to brawls in the streets and subsequent media vilification of the associated styles of dress and music. As the fifties became the sixties, many bands would rise to prominence in part by association with this phenomena. The wave that broke in the form of Beatlemania had long been building as mod, rock, and other youth subcultures.

To take it from Pistol, you would think that Malcolm McLaren invented youth culture, or at least harnessed it into a marketable form for the first time, never mind that the “Establishment” he and the other characters constantly rail against includes, in addition to Rod Stewart and the Queen, products of the same process that will eventually embrace the Sex Pistols themselves. It’s one thing for the people to have been ignorant of this history; quite another for the show to be. (A notable exception to this is reggae, which one band member refers to as “the music of the disenfranchised,” in an attempt to slow down early versions of “Anarchy in the UK” — everything in Pistol serves a purpose.) Glen Matlock, the only member of the band who can really play his instrument, is frequently an object of ridicule and eventually thrown out of the band for his love of the Beatles who, in this context, are symbols only of the mainstream conformity, which, not incidentally, is synonymous with the stifling effects of knowing how to play music.

Both Jones and McLaren repeatedly insist that it’s not the competence of the music, but the passion with which it’s played. In a particularly embarrassing rehearsal scene, Jones stands over Matlock, wielding a stolen Les Paul, responding to each of Matlock’s calls of “Edim9” or some apparently impossibly complex chord with a ringing power chord played, in his words, “Like a punch in the face.” This initial bravado eventually transforms into the slurred mutterings of Sid Vicious, Matlock’s replacement, who defends his near-total inability to play his bass by claiming that the music doesn’t matter at all, only the look.This is not a mutation, much less a deterioration of the original spirit, but its apotheosis. Performance is always a blend of technique and the spirit that infuses it, and the veneration of one while denigrating the other is usually an excuse for inadequacy, not superabundance.

It’s a constant refrain throughout the show: “authenticity,” over and against both inertia and corruption. McLaren’s early enthusiasm is motivated by his desire to “shake things up,” though it’s never quite clear what he means by that, since by the time the show comes to a close, the band has performed exactly as he had planned, and he vows to destroy them for becoming too much “like a rock band.” This despite Johnny Rotten’s own claims to honesty and authenticity, which increases with his notoriety in two forms: first, as the utter transparency of his financial greed, and second, in his eschewal of what he claims is the lie of the rock concert, in which the audience is kept at a distance from the performer.

The Sex Pistols’ tight-quartered response to this is far from unique, and it persists to this day in thousands of clubs, warehouses, and basements, but it can really only be partial. Apart from the bare facts of someone playing and someone listening, there’s a social function that is satisfied when the roles of performer and audience are adhered to, however creatively. It has to do with how theorists describe ritual as a many-layered process of drawing together and separating out: first between insiders and outsiders, then practitioner and congregants, all the way down to subject and object. But the result is not endless fragmentation. Rather, in the performance of all these divisions, a higher-order interrelation is created, drawing even insiders and outsiders under the banner of a reality in which the whole thing is possible to begin with.

Perhaps this is why rebellious youth culture is particularly amenable to capitalistic reproduction and profit. When the local practice can no longer exhaust the paradoxical ritual need to separate out and draw together, that energy is carried up into increasingly abstract domains. The subculture is transformed into a vehicle by which money-makers can suspend the ritual process in the purely positive, while maintaining the veneer of opposition: constant resistance, constant submission. Sure, Johnny Rotten may have been face-to-face with his audience, but now we are delivered his music by the Walt Disney Company, and for everyone “in the know” shaking their heads, there will be a thousand who take it as at least a faithful record of the real thing and shell out.

Of course, Pistol makes this case without meaning to, instead offering the Sex Pistols up as a symbol of hope and an inspiration for the future. Punk, meanwhile, remains a living form, moving constantly in new directions not so much in the face of consumer culture as behind its back, in its shadows, playing with the boundaries of audience and performer, not rejecting them. The assimilation into the mainstream of its most recognizable aspects is a liberation from the suffocating ritual of cultural rebellion; failure always offers a glimpse of freedom. It would therefore be easy to laugh off an attempt to épater les bourgeois when the bourgeois were raised on just this kind of épatage. But Pistol and the band it’s based on are something else. Capitalism is a religion, and, as many have said, only the faithful can blaspheme.

Jack Hanson is a writer living in New York.