More Like Suckboi

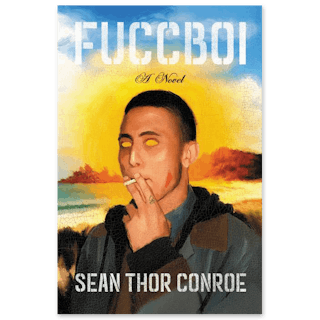

Sean Thor Conroe’s debut novel ‘Fuccboi’ captures nothing of our current moment

During the final years of the Obama era, there was one question on everyone’s mind: What is a fuccboi? The term’s origins (and spelling) are murky — a loser, or maybe homophobic prison slang — but however it began, fuccboi quickly became shorthand for young men who are unwilling to commit to a relationship and probably listen to Drake: an epithet granted the lazy application and lack of force once reserved for “hipster.” Derivations like the softboi also had their day in the sun before we all basically moved on to more pressing issues, like men who text too much and then not at all. So when it was announced that a major publishing house would be releasing a book of literary fiction titled Fuccboi in 2022, more than a half a decade after the explainers had dried up, bookish observers paused the latest round of the Franzen Accords to pose another question: What?

Fuccboi, written by Sean Thor Conroe, is narrated by Sean Thor Conroe, a twenty-something Swarthmore graduate living in Philadelphia in the late 2010s. Conroe delivers Postmates, develops extreme eczema caused by a mysterious immune disorder, films rap videos which closely resemble ones made by Conroe the novelist, and occasionally works on his book. In between, he reads autofiction luminaries and feels guilty about past relationships. The book functions as a kind of younger millennial Künstlerroman, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Stan.

Besides the titular fuccboi, Conroe feels like another detested strawman brought to life: the lit bro. Reading Infinite Jest freshman year literally changed his life, after which he “tried shrooms and quit basketball to go abroad to study writing, only to cultivate a nicotine addiction, a molly habit, contract herpes the second (or third) day I was there (was never sure which girl it was), and end up engaging in a semester-long flex beef with my creative writing prof.”

And so he commits to “That Art Life.” Channeling Knausgaard, Conroe realizes that the writer’s “attempt to express the inexpressible was the antidote to the other option: wallowing helplessly in repression, shame, as you grew more alienated, hateful, consumed by suffering, till eventually you became a school shooter or Hitler.” Other revelations come by way of Tao Lin, Sheila Heti, and Heidegger. Of his more recent past, we’re told that he wrote a book-length thesis on Roberto Bolaño’s “2666 (2004), sexual assault, and the Juárez femicides.” Post college, he worked at a weed farm in Humboldt and tried to walk across the country. The trip was a failure, which he turned into a 165,000-word Walk Book draft. That book doesn’t come to fruition, but eventually Conroe begins writing Fuccboi.

The first thing one notices about Fuccboi — possibly the only thing many will notice — is that it is written in a mix of laundered rap slang and college-seminar buzzwords. At times, especially in the early pages, it feels satirical, like an updated Malibu’s Most Wanted. Very briefly, I had high hopes for a millennial Big Lebowski: a perma-stoned man-child aimlessly gig-working through the contemporary wasteland. Then the novel takes a turn for the sincere that comes off as cynical, or at least as a parody being passed off as sincere, à la My Pafology. Conroe is 30, but Fuccboi sometimes feels as if a Gen Xer wrote a book for the platonic millennial targeted by those pastel-hued subway ads: “I was a brokeboi fuck with a bed so shitty that this alone should have disqualified me from any and all forms of intimacy.”

His use of slang occasionally approaches the abstract, as with “railed.” Initially Conroe talks about railing stimulants — understandable. But he later rails Advil, Claritin, a banana, and coffee, leading me to believe he’s using a word commonly associated with insufflation as a catch-all for ingestion. Which would be no problem were he strictly using it with bananas and coffee, but to use the same word for things that can and things that cannot be snorted seems clumsy and confused, raising questions of intentionality— a pattern reflected in the novel as a whole. Fuccboi is uneven, not only in quality but in tone. Is he serious, kidding, or just getting it wrong?

Beyond the slang, there is the question of formatting. Citing poetry readings and SoundCloud rappers, Conroe hits on the idea of using a line break after nearly every sentence, so his close read of the part about Knausgaard’s My Struggle that analyzes Hitler’s My Struggle looks like this:

I was at the part in Knausgaard’s My Struggle: Book Six (2018) when he finally started talking about Hitler.

About Hitler’s struggle.

Finally getting around to explaining the series’ title.

About damn time.

How that fool Hitler initially wanted to be an artist.

Had no idea!

And a poetry reading is described as such:

Everyone who read was whatever till this girl who seemed not much older than me went up there.

Sleeve-zatted like a muhfucker.

Fkn hella swagged out.

Super sexy but in a way my brain couldn’t objectify due to my awe/admiration/fear of her.

Conroe explains the way he talks with his peripatetic childhood: “Ages 1–5 Japanese; 5–8 Gaelic-Scottish accent, UK slang [he says “innit” a lot]; 8–9 upstate New York, insulated American white folk talk; 9–11 Sactown Latino-Black hood speak; 11 onwards Santa Cruz surfer speak.” The problem lies not in what might be termed either code switching or cultural appropriation, but in the book’s rampant use of the same worn-out text speak as a Verizon commercial. Characters include side bae, peripheral bae, ex-roomie bae, editor bae, and ex bae, the last of whom provokes lingering feelings that make Conroe feel “sus af.”

For a book called Fuccboi, it’s striking how little sex is contained within. Some of the most prurient details come from a visit to the urgent care for the eczema flare-up:

It was honestly so nasty removing my 4s in the examination room.

Fkng putrid.

It wasn’t even bumps anymore; there were heel-to-toe bubbles that had busted open.

Huge gashes down the middle.

Dead skin dangling.

The nurse, he was such a champ. Made me feel like not a leper. Grabbed a bucket and carefully cleaned my feet with saline solution.I felt like Jesus.Then he flipped me over and shot my right butt cheek full of some anti-inflammation antibiotic.

It is, genuinely, a pretty funny scene of slapstick body-horror (although historically Jesus was the one doing the curing of lepers and washing of feet — another instance of serious, kidding, or getting it wrong?). Which gets at what’s so bizarre about the book: underneath all the gimmicks, it’s not as bad as it might have been, which somehow makes it worse.

Conroe’s novel was initially championed by the late Giancarlo DiTrapano, founder of the publishing house Tyrant Books. DiTrapano had a celebrated record of cultivating promising but commercially tricky young writers like Atticus Lish, Megan Boyle, Scott McClanahan, and Nico Walker, an Army vet who was in prison for bank robbery when DiTrapano encouraged him to write the autobiographical novel Cherry. (It was eventually sold to Knopf and adapted into a movie.) Not long after DiTrapano died in March 2021, Fuccboi was bought by Little, Brown for a six-figure sum. DiTrapano’s endorsement goes some way to explaining the hype around Fuccboi, and the novel might have better fit in among the internet-inflected novels released by Tyrant. But the novel is now being marketed as something far broader in scope, a survey of the way we live now.

Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Jay McInerney calls Fuccboi the coming-of-age novel this generation deserves (meant as a compliment). McInerney’s Bright Lights, Big City is the definitive novel of the Vintage Contemporaries ‘80s, but he was more recently the Journal’s wine columnist. Through no fault of his own, he may not be in the best position to spot the millennial zeitgeist. It’s not just McInerney, though. Vulture says the same thing. It’s been blurbed by Tommy Orange, Sam Lipsyte, and Sheila Heti. Hermione Hoby’s critical review in Bookforum calls it a “big swaggy flex of a debut.” In the jacket copy, Fuccboi is described as “examination of masculinity under late capitalism.” As of now, most of the of-the-moment millennial novels have been written by women. Publishers and critics both seem to want Fuccboi to be the straight millennial male swing at things.

It’s not; Conroe is a voluntary isolate, suspicious of his friends and uneasy around his family, both of whom take great pains to help him. The closest he gets to going on dates is imagining elaborate encounters with the derm bae testing him for leprosy. He is, in short, far too weird to be representative of anyone. How many other books were written in the Notes app and on a typewriter? Fuccboi is neither a survey of modern heterosexual relations nor a glimpse of youth gone wild, like Less Than Zero or Euphoria. If anything, the viewpoint is strangely conservative. He listens to Joe Rogan podcasts and is preoccupied with the idea that his peers are “too concerned with pushing their woke agendas, to actually challenge themselves to consider anything they didn’t already think.” He’s not red-pilled, he’s just confused; at various times, he considers how woke an action would be, then worries he’s choosing to do the woke thing just because it’s woke. It’s a pessimistic way to live, but fortunately it doesn’t match with my experience of modern masculinity — at least not among the readers of Knausgaard, Bolaño, and DFW. Most of my peers are well aware of the inane extremes of PC culture, but also cognizant of the fact that they come from a needed, well-intentioned place. I doubt they go through the day worrying about how woke things are. Mostly, they’re just trying to read good books.

In My Struggle, Knausgaard writes with equal intensity about the profound and the mundane, and this juxtaposition raises the latter to the former. What is life if not birth, death, and a lot of cooking and cleaning? Fuccboi has dozens of pages about homeopathic eczema treatments and late-night snack “mishes” and auotofiction exegeses, but only hints about the dissolution of his relationship with ex bae — the precipitating event behind the crisis of self that spawned the novel. We know there was an abortion involved, because he says, “ex bae’s abortion was what fucked everything.” But the particulars are mostly gestured at. The same goes for his strained connection with his father, who lives in Japan, teaching English and doing Wim Hof exercises; with V, a fellow writer with whom Conroe feels competitive; and with editor bae, who initially wants to sell his novel, asks him to cut the “rape-y parts,” then abruptly cuts off all communication with a text message ending in “Have a good summer!” It’s not too hard to fill in the blanks with topics as familiar as breakups and dads, but by failing to mine the heavy stuff to the same depth as the ordinary, Fuccboi becomes the opposite of its title: a lingering relationship short in stimulation.

Hanson O'Haver is a writer in New York.