Imagine that it’s 2008, and a 13-year-old boy, soon to be Bar Mitzvahed, is at the Miley Cyrus “Best of Both Worlds Tour.” He’s really there for the opening act, the Jonas Brothers, but he dutifully wears the Miley t-shirt he bought upon entry, having convinced himself that confessing his affection for the brothers is tantamount to coming out as gay (and that stanning Miley Cyrus, somehow, is not). Shortly thereafter, on a teeny-bopper gossip site called “OceanUp,” he’ll see a photo of Nick Jonas playing catch or maybe frisbee on the beach with his brothers, and the sight of Nick’s unusually large and sun-burnt nipples will awaken something in him. A year after that he will come out, as both gay and a Jonas Brothers fan, and hitch a ride to Jones Beach to see them in concert. By the time he’s 18 he will go away to college, begin having sex with men, develop marginally better taste in music, and more or less forget the Jonas Brothers altogether, treating the news of their break-up and subsequent solo projects and eventual comeback album with smug disregard, as one might an old ex-boyfriend.

In Kaitlin Tiffany’s sharp and very funny new book, Everything I Need I Get From You, the subject is fangirls, not fanboys, and the band is One Direction, not the JoBros, whose eventual obsolescence was hastened by the British quintet’s arrival stateside in 2012, a development I took as a personal affront. But the stories — of teenage identities shaped in and by the thrall of parasocial obsession, of the internet as a site of youthful conspiracy, idolatry, and lust — are all the same. Fangirling, after all, is the lingua franca of the young, the newly horny and maladapted. And if fandom is not exactly native to the internet, the internet is native to fandom. After all, some of its earliest practitioners were Deadheads, Tiffany writes, who “innovated the idea that the internet might be organized by affinity,” providing fans — and, she argues, young women in particular — with a place to indulge infatuations that, in the harsh and imperious world beyond the monitor, were taken to be signs of duress if not genuine lunacy.

Fangirling is the lingua franca of the young, the newly horny and maladapted.

Writing as a Directioner reintegrated into civil society, moving artfully between reportage and memoir, fanspeak and critical analysis, Tiffany avoids the default condescension to which fangirls are often subjected and takes their exploits seriously, teasing out the relationship of fandom to both individual identity and online community. Indeed, Twitter and Tumblr are to fans as forests are to felidae, places of congress and also infighting. When a pop culture news aggregator such as Pop Crave posts some benign data point like, “Harry Styles is the fastest male soloist to reach 200 million streams on Spotify,” you will invariably find a reply, perhaps by an account called “Comrade Barb,” levying accusations against Styles fans of something called “mass playlisting,” and then a reply to them, from a militant Swiftie, clapping back: “didn’t work for Nicki tho.” Whether any of these things are related is beside the point: the organizing principle of life online is devotion, and it must be expressed insistently and combatively, even if your fave isn’t a male soloist and your intervention therefore entirely irrelevant.

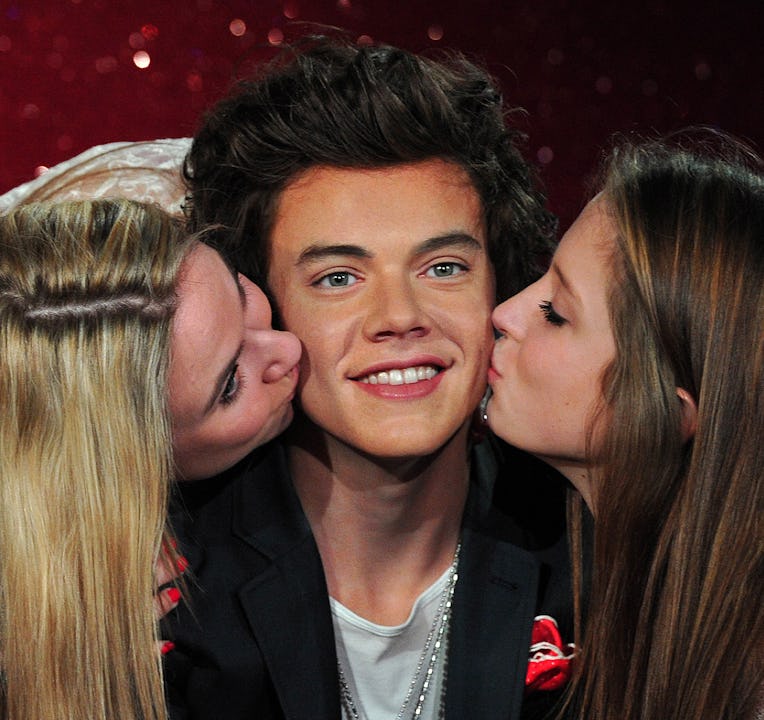

It was One Direction fans who “pioneered the idea of a Twitter stan war,” argues Tiffany, and who identified in these five slender British boys a calling commensurate to their capacities for enthusiasm and online sorcery. “They invented new methods for getting what they wanted,” she writes, “which included methodical and bureaucratic techniques as teaching international acquaintances how to fake American IP addresses and thereby accrue Spotify and YouTube streams that would count on the Billboard charts.” If the reader does not exactly leave with an understanding of why One Direction, and not some other handsome teenage musical act, captured Tiffany’s heart, this is by design. Notwithstanding its occasionally overlong forays into the annals of 1D lore (no small contingent of their fans, known as “Larries,” are deeply invested in a theory suggesting Styles was secretly dating his bandmate Louis Tomlinson, which sounds pretty hot), Tiffany’s book reads more as a disquisition on young womanhood, the fangirl’s bildungsroman, than the story of a band. “What I would like it to be,” she notes in the introduction, “is a book that explains why I and millions of others needed something like One Direction as badly as we did.”

The organizing principle of life online is devotion, and it must be expressed insistently and combatively.

Tiffany does so ably, guiding the reader down the rabbit hole of Beatlemania, or through the emergence of poptimism, or on a quest to find “the shrine to Harry Styles vomit,” which is a thing that exists in Calabasas, where Styles was once photographed puking by the 101. Tiffany knows that behavior like this is what we call cringe, to adopt the parlance of her subjects. But she does not take the bait, as a lesser reporter might. Instead, she examines the fangirls’ natural instincts for archiving and preservation, and shows how these instincts fortify their digital sororities. These are not spaces one ventures into casually, at least not with any hope of achieving fluency (though I consider myself well-versed in stan vernacular, a few of Tiffany’s attempts to explain popular One Direction memes in prose form went over my head). “But this too,” the inscrutability of fanspeak, “is part of Tumblr’s culture,” she writes elsewhere. “The shrine to Harry Styles’s vomit is preserved primarily by my resolve to wade through shards of information and broken links to find it.” There, in the digital mesh of URLs and memes, the amusing and invasive curiosities of stans can thrive beyond the jurisdiction of those who wish to police them.

These are often well-educated, adult men — cranky in temperament and elitist in sensibility; intimidated, perhaps, by the populist forces that may threaten their position as tastemakers — and Tiffany does get a few good licks in, though with more grace than what usually characterizes disputes between cultural critics and bellicose stans (sophistry, delusion, bad-faith, etc.). But these men are mostly ancillary to the story, and their tastes well-documented. Citing the Times’ Jon Caramanica’s reviews of One Direction’s albums, in which he mocks their fans as “squealers” and positions them as a kind of scourge on the band’s well-being, she teases out the history of such portrayals of young women as feral and unsophisticated, portrayals which are of course older than the history of boy-bands themselves.

Caramanica is low-hanging fruit compared to Theodor Adorno, a recurring adversary of poptimists who was, frankly, at his most dogmatic and least convincing when writing about pop music, which he considered “catharsis for the masses … which keeps them all the more firmly in line.” Surely, then, he’d have scoffed at the notion of boy bands as a conduit to self-actualization (he is wrong). But he did not live to see the internet (he is lucky). To “hang over the radio all day,” Adorno wrote, “one must have free time and little freedom.” But this, Tiffany notes, is “the default condition of a teenager,” and the internet has bestowed on teens such liberty that One Direction fans have at various times mounted efforts to both a) thwart a rumored assassination attempt against Styles with the hashtag #HarryBeCareful and b) raise funds to buy the band out of their demanding record label contract. Adorno cautioned that popular entertainment would “complement the reduction of people to silence,” when in fact online fandom has catalyzed in its ranks an exultant if delusional kind of insubordination.

This is, sometimes, very bad. So Tiffany takes a thorough account of Stan Twitter’s misdemeanors, from threatening to “fucking mutilate the insides” of a GQ reporter to sending death threats to the teenage daughter of the woman rumored to be Jay-Z’s mistress. “Stan Twitter harassment campaigns do not approach the level of Gamergate,” she argues. “Yet, any kind of harassment at scale relies on some of the same mechanisms,” namely “a tightly connected group identifying an enemy and agreeing on an amplification strategy, providing social rewards to members of the group who display the most dedication or creativity, back-channeling to maintain the cohesion of the in-group, which is always outsmarting and out-cooling its hapless victims, all while maintaining a conviction of moral superiority.” These tactics do sound a lot like the fringe groups who’ve turned your grandparents’ Facebook timelines into one giant banner ad for ideological extremism. Except the fangirl marshals her resources not in support of white nationalism and blue lives and book bans but ultra-famous pop stars, sometimes as many as five of them.

Which brings us to today’s bizarre state of affairs, where celebrities, endowed with the power of idols, are accosted by fans in the streets asking them to yell “gay rights!” on camera; where Ariana Grande is hailed as a proletarian hero for licking a donut she didn’t pay for and saying she hates America; where Grimes, after her split from the world’s richest man, stages a photoshoot for paparazzi in which she leans dramatically against a fence and reads The Communist Manifesto, a perceived gesture of solidarity with the normies she’d rebuffed for Elon Musk. For a moment, one could believe she’d rejoined the huddled masses, shirked technocracy once and for all.

Just as quickly, Grimes clarified that she is not a communist and is very much “still living with E,” that she was just trolling the paparazzi. “At its best,” Tiffany writes, “fandom is a joke that never ends.” Sometimes, though, the joke is on us, the fans who exert baffling amounts of energy in order to boost our fave’s Spotify numbers, defend their artistic merits, and harass their haters. In return, we want to be let in on a secret, to witness the fruits of our screen time, to see the causes we care about championed by the celebrities we worship. But perhaps, Tiffany suggests, fandom is most meaningful as a series of signposts, a process by which we come of age — or in my case, come out — and begin to champion our enthusiasms, and ourselves. Which is all celebrities ever do, anyway.

Jake Nevins is a writer and reporter living in Brooklyn.