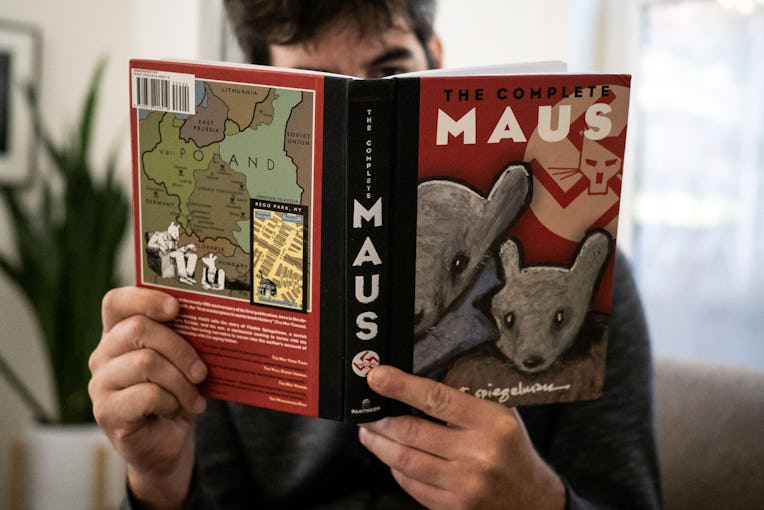

Late last month, the McMinn County School Board in Tennessee opened another round of the endless and demoralizing culture wars by voting to remove Art Spiegelman’s 1980 graphic novel Maus from its 8th-grade curriculum. The brouhaha was not surprising given the context: the recent Criticial Race Theory panic and the consequent banning of Black authors’ books, even those of established literary giants like Toni Morrison, and the official distortion of Holocaust memory taking place in Eastern Europe. To those that reacted immediately, the Maus ban seemed to confirm and reveal the real underlying fascist logic of the process, one that was now directly coming for the memory of the Holocaust and the Nazis.

Closer inspection of the reasoning of the school board didn’t reveal overt antisemitism so much as prudishness and stupidity. It wasn’t the book’s examination of the Holocaust that was objectionable, it was its attendant nudity and cursing. A group of skeptics of the notion that it was an instance of antisemitism, perhaps somewhat gleeful at the prospect of showing up hysterical libs, pointed this out, triggering a backlash. As a result, many people spent Holocaust Remembrance Day parsing the minutes of a rural school board meeting to look for clues into America’s psyche. Not-entirely-plausible psychoanalytic theories were even proposed to connect McMinn County’s purported sexual squeamishness to parts of the fascist personality.

What was notable was that the controversy played out largely on the left itself and became a proxy for other debates, like whether Trump should be understood as a fascist phenomenon. Spiegelman gave ammunition to both sides in the argument, at one point calling the school board’s decision “Orwellian,” but also saying on CNN that “they may possibly not be Nazis, maybe… because having read the transcript and the problem is sort of bigger and stupider than that. They really genuinely focus on… some bad words in the book.”

The fallout from the Maus fiasco has now cascaded. While discussing it on The View earlier this week, Whoopi Goldberg, while defending the book from the school board's depredations, rather puzzlingly claimed the Holocaust “was not about race.” This immediately triggered another round of denunciations, mostly from the Right, eager to label the comment antisemitic. That Whoopi Goldberg said what she said on The View was the necessary consequence of a perspective tainted by “CRT” and “intersectionality” or whichever ideological bogey they’ve chosen this week; part of a longstanding right-wing reflex to smear Black people whenever possible as antisemites and drive a wedge in the progressive coalition. Andrew Sullivan helpfully tweeted out the subtext: “Antisemitism in America today is often a subset of anti-whiteness.”

One part of the present age is the fracturing and fading of a shared sense of the meaning of the Holocaust and the Nazi era.

Goldberg apologized and was suspended from The View for two weeks, an absurd overreaction when harm was obviously not meant. Goldberg’s comments were not tendentious, just factually wrong, probably the result of a parochial American understanding of the term “race.” There is no possible interpretation of the Holocaust that doesn’t include explicit Nazi racism as the determining force; the fact that this is not universally known is troubling. But if you read Goldberg’s remarks carefully, she was attempting to take the discussion to another register: “But it’s not about race. It’s not. It’s about man’s inhumanity to other man…The minute you turn it into race, it goes down this alley. Let’s talk about it for what it is. It’s how people treat each other. It’s a problem.” Goldberg was not being overly “woke,” as the Right attacks imply, but attempting to return the discussion to an kind of older shared understanding of the Holocaust as generalized moral catastrophe, above and beyond the political and cultural struggles of the contemporary U.S., the example above all others of the dangers inherent in the human condition.

It would be easy to decry the general state of stupidity and ignorance in the country, the sorry state of education and historical awareness, the unceasing superficial controversies. There is plenty of that to go around. But I want to suggest something else that is going on in this dustup and its contemporaries, which can’t be remedied by getting mad online or through taking punitive measures against individuals: that one part of the present age is the fracturing and fading of a shared sense of the meaning of the Holocaust and the Nazi era.

We still know the words, we still know the images, but how it all hangs together as a system of historical and moral meaning is starting to lapse and fragment among various party lines. We see this in the various abuses of Holocaust imagery, like in the anti-vaxx movement. And we can see it in the disjointed and strange responses in the aftermath of the Maus debacle, where people jump at the idea of Nazis in the boondocks. Goldberg’s more old-fashioned generalized-moral-outrage picture of the Holocaust gets chided for its lack of racial specificity, but this time by the Right.

We still know the words, we still know the images, but how it all hangs together as a system of historical and moral meaning is starting to lapse.

The reason these moments create such confused and anguished reactions is that they are experienced as a crisis: the loss of a central moral guidepost of our civilization. Theodor Adorno wrote, “A new categorical imperative has been imposed by Hitler upon unfree mankind: to arrange their thoughts and actions so that Auschwitz will not repeat itself, so that nothing similar will happen.’’ Sure, but what will happen when we only have a vague understanding of what actually took place in Auschwitz and why?

I’m not sure how to remedy this, and I am certainly not going to give a sermon on the virtues of education and reading. But perhaps it shouldn’t come as a surprise that these culture wars seem to have the same effect on culture as real war has on life: destruction. Half-remembered pasts become brickbats for wilfully obtuse goons looking for an outrage kick. They are not real “teachable moments,” “debates” or don’t “raise issues,” they just break the fragments of history into smaller and smaller shards until, perhaps, we can’t tell what they were in the first place.