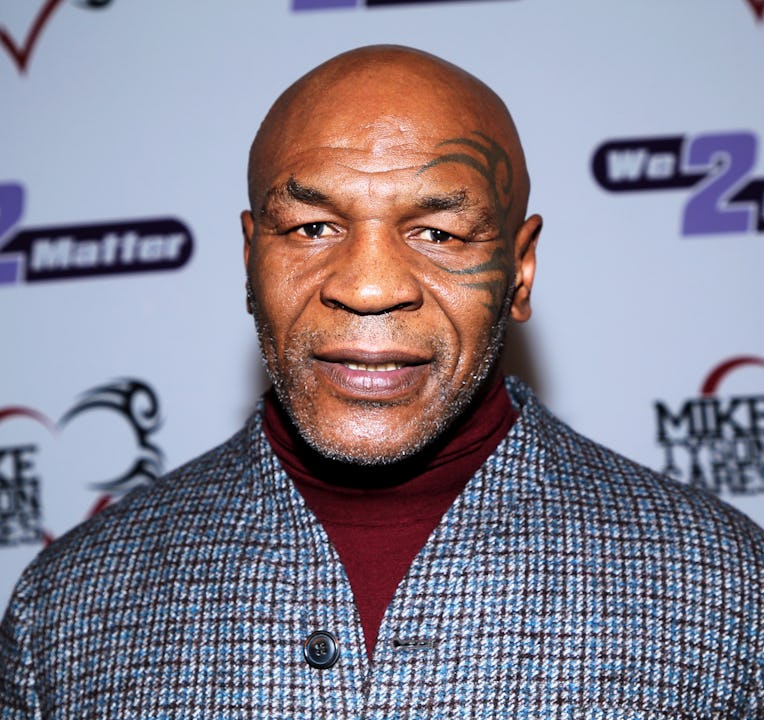

There’s a story Mike Tyson used to tell about his objectively horrifying childhood growing up in Brooklyn in the 1970s, and even years later as a grown man, the heavyweight champion of the world, recalling it still brought him to the verge of tears.

He was in the first grade, and he’d recently been forced to start wearing glasses to correct his nearsightedness. One day an older kid took the glasses off his face, folded them in half, unscrewed the gas cap from a parked delivery truck, and slipped them into the gas tank. Tyson didn’t even like the glasses — hated wearing them, in fact — but he was stunned by this act of pure malice. Unlike the many robberies he’d already seen and suffered by then, this one benefitted the perpetrator not at all. It was cruelty for cruelty’s sake.

I found myself thinking of that anecdote last week as I watched the TMZ video of Tyson being antagonized by a fellow passenger on a JetBlue flight as it waited on the tarmac at San Francisco International Airport.

Some guy, seemingly intoxicated, starts out merely annoying. He recognizes Tyson and starts talking to him from the row behind as his friend films, giggling, from across the aisle. Later, according to a statement issued by Tyson’s representatives, the man threw a water bottle at him.

Another video taken from a different angle shows the result. In this one, Tyson has turned around and is standing over the row of seats, repeatedly striking down at the man with a barrage of short, quick punches. According to witnesses, Tyson then walked off the plane and later spoke with police, who did not detain him. The man who was antagonizing him can be seen later, making an almost cartoonish pouty face as he shows off the mostly cosmetic wounds on his forehead.

“My boy just got beat up by Mike Tyson,” the cameraman says, before asking his friend to show off the bruises. “Yeah, he got fucked up. Just trying to ask for an autograph, man. I don’t know what happened.”

What happened, it would appear, was a classic case of fucking around and finding out. And for a change, here the internet response was fairly unified. No diatribes about the relationship between violence and free speech or even the deteriorating etiquette in air travel. Instead, mostly what people wanted to know was: Who in the hell would mess with Mike Tyson?

But considering the many lives he has lived up to this point, not to mention the bizarre role he currently occupies in our collective consciousness, can you blame Tyson if he might think that the answer to that question is: damn near everybody.

People act weird around Tyson, weirder even than they act around other celebrities. I’ve seen it firsthand at MMA events Tyson has attended. Fight fans in particular seem to be possessed of a compulsion to shake his hand and tell him what he’s meant in their lives. Just last month, Tyson was at a comedy event in Hollywood where a man pulled a gun, cocked it, then was defused by a hug from Tyson after an excruciatingly awkward conversation about the “inspiration” Tyson had provided.

For anyone else, this would have been a profoundly strange experience. For Tyson, it seemed at most mildly inconvenient.

Part of this has to do with the specific niche of fame that Tyson occupies. Though he initially became famous as the most terrifying boxer of the ’80s and early ’90s, now Mike Tyson is mostly famous for being Mike Tyson. People who know and care nothing of his boxing career still know Tyson for his many cameos and his ubiquitous media presence. I once taught a seminar on American sports culture to a group of Chinese college students who didn’t recognize a single other American sports star — not Tom Brady, not Lebron James, definitely not any baseball players — but they knew Tyson instantly, thanks mostly to The Hangover.

They were aware that he became rich and famous. Certainly they know that he bit off a piece of Evander Holyfield’s ear in their 1997 rematch, which is why his commercial marijuana company is currently selling “Mike Bites,” a THC-infused gummy in the shape of that deformed ear (because no controversy is so bad that it can’t be monetized eventually).

But really what people know, or have at least absorbed? It’s that Tyson is capable of shocking feats of violence and will snap on occasion. This volatility is built into his whole brand. It’s why it’s especially funny for the guys in The Hangover to have accidentally stolen Tyson’s tiger as opposed to, say, Siegfried and Roy’s. Most celebrities realize they have more to lose than to gain by going off on a civilian, even when it’s justified. Tyson might realize the same thing, but his persona is that of a guy who will do it anyways. We might want to punch an annoying stranger on a plane; Tyson will actually do it, even now.

His reputation is not unfounded. Tyson’s boxing career was filled with stories of extracurricular violence. There was the time he battered rival boxer Mitch “Blood” Green outside an all-night custom tailor shop in Harlem two years after they fought in Madison Square Garden, or the time he bit Lennox Lewis’ leg during a press conference melee. These incidents mostly only aided his mystique. Here was a guy so good at professional violence he occasionally did it pro bono.

We might want to punch an annoying stranger on a plane; Tyson will actually do it, even now.

But then there was the stuff that even fight fans couldn’t easily excuse, such as his history of violence against women. Tyson once said that the best punch he ever landed was on ex-wife Robin Givens. He was convicted of raping an 18-year-old woman in 1992, and served almost three years in an Indiana prison. Tyson angrily maintained his innocence, and later told Greta Van Susteren in an interview, “Now I really do want to rape her and her fucking mama.”

While doing media to promote his 2002 heavyweight title fight with Lewis, Tyson told a female reporter, “I normally don't do interviews with women unless I fornicate with them, so you shouldn't talk any more, unless you want to, you know.”

At the time, some wrote that one off as savvy self-promoting. Tyson knew that his appeal to the public was that of a savage lunatic who might do anything at any time, damn the consequences. A day earlier he’d greeted a group of journalists who visited his training compound by suggesting he might, “close the gate and beat your fucking asses, you all crying like women.” This was him leaning into his persona, critics argued. But it also felt like Tyson forcing us to confront exactly what it was we liked about him, even as we abhorred it.

The Tyson of today exists in a weird space between all-purpose celebrity curiosity (one could easily imagine him on any of the dancing, singing, or rehab shows at any point) and venerated elder statesman of sports. It’s as if he’s hung around long enough, and endured enough mini Greek tragedies in his own life, that his many sins are forgiven or at least somewhat forgotten. Still, it’s like we can’t resist poking the bear on occasion if only to find out whether or not it still has teeth.

Did Tyson ever have a chance to be normal, even by famous pro boxer standards? Not really. As a child he went from the streets to reform school to what was essentially a boxing gladiator academy that taught him fighting fundamentals but almost nothing about being a person in society. The story goes that, while a teen living with famed trainer Cus D’Amato, Tyson once seized the plate of food that was set in front of another boy at mealtime. When D’Amato’s wife chided him for not waiting his turn, D’Amato stopped her, saying this was precisely the attitude Tyson needed. Taking food from the mouth of another human was the boxer’s whole vocation. This was a good thing he’d done. You go ahead and eat, Mike.

Not so many years later, he was the youngest heavyweight champ in history, making millions per fight, with the whole world waiting to see when and where and how he’d detonate next.

For Tyson, the volatility always came with a surprising vulnerability. There’s probably no heavyweight champ in all of boxing history who’s cried in as many interviews, or shared as many heartbreaking stories from his youth. I remember a young Tyson getting choked up talking about the realization that, as hard as he worked in the gym to make money as a fighter, he always found himself surrounded by people working just as hard to swindle him out of it. In Brownsville, the older boys roped him into their burglary crews because he was small enough to fit through the windows, and then they often cut him out of the money he stole. Later he grew up and met Don King, and it probably felt like not much had changed.

What’s made Tyson so fascinating for so long is the rage that’s right there on the surface, but also the sadness and the confusion and the lack of control. He was always part monster and part lost child, an explosive mix that he grappled with in full public view while we watched from a safe distance. He knew this, and he played to it — but he also found ways to remind us that it was as much our sickness as it was his.

Maybe there’s a culture that could create a person like that and then just let him sit on an airplane in peace, but it’s not this one. We are still eager to watch when someone is dumb enough to poke the bear. We are still enjoying it too much.

Ben Fowlkes covers combat sports and sometimes writes fiction. He lives with his two daughters in Missoula, Montana.