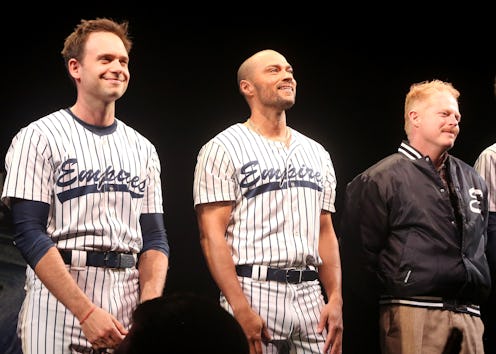

The title of Richard Greenberg’s Tony-winning play “Take Me Out,” now revived on Broadway for the first time in 20 years, is a kind of all-purpose pun, gesturing toward the work’s two preoccupations: baseball and homosexuality (a doubleheader, if you will). To begin, Darren Lemming, the princely, biracial bigshot of the fictional New York Empires, comes out of the closet, coolly telling reporters at a post-game press conference that he likes men. Later on, in the play’s final innings, a wild pitch quite literally takes a player out, in keeping with the dramatic principle of Chekhov’s gun, which figures here as a lethal fastball. Those in the audience are prohibited to take out their cell phones, which for the duration of the play are magnetically sealed in something called a “Yondr pouch,” presumably on account of the show’s copious full-frontal nudity. On stage at the Hayes Theater, limned by a bank of showerheads and stage lights, penises are on full display, inviting theatergoers to take in the provocative spectacle of masculinity under siege in a Major League Baseball locker room.

It’s easy to imagine what a lightning rod the show must have been to audiences in 2002, first in London and then at The Public. Greenberg’s clever, incendiary play premiered in the deadly wake of the AIDS crisis, not long after the passage of “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” and a few years before the tides of public opinion shifted in favor of same-sex marriage. For the most part it remains so, despite new causes to promote and worse bills to oppose, because of an enduring fixation with the prospect of a gay man in a pro-sports locker room. Liberals imagine him plunged into a cesspool of homophobic meatheads, the beau idéal of representational politics. The actual homophobes, meanwhile, picture him popping a semi in the showers, titillated by the sight of all those soapy, flaccid dicks.

In reality, time and again, a generally ghoulish parade of speculation and intrigue has driven teams away from gay athletes altogether — “I wouldn’t want to deal with all of it,” NFL coach-turned-talking head Tony Dungy said of Michael Sam — and the ones that do tend to come out only after they’ve retired. So, with the exception of football player Carl Nassib, who’s not currently signed to an NFL roster, there are no openly gay men in the four major American sports today. The gay Olympian skier Gus Kenworthy, for what it’s worth, appears to have ditched the slopes to join Ryan Murphy’s ever-multiplying company of hunky white gay and gay-for-pay sketch performers.

So it is funny and naive when Darren Lemming, described as a “one man emblem of racial harmony,” matter-of-factly tells the press he hopes to “ward off distractions” by coming out, wrongly thinking himself impervious to prejudice or, worse, pity. But the team’s sacred chemistry is disturbed; their “stray homosexual impulses,” as one puts it, are newly charged. “It’s the Billy Budd thing,” says Kippy Sunderstrom, Lemming’s closest teammate and the play’s bookish narrator, who joins the rest of the ball club in overeager displays of tolerance and salutation. Until the bullpen starts to slump, and the country bumpkin Shane Mungitt (one in an ensemble of jock-ish stereotypes prone to malapropism, including one subverbal Japanese pitcher) is promoted to the Empires from the minor leagues. “A pretty funny buncha guys,” he tells the press after his debut. “But every night t’hafta take a shower with a faggot?” He is punished, to the team’s relief, and then briskly reinstated.

The team’s sacred chemistry is disturbed; their “stray homosexual impulses,” as one puts it, are newly charged.

“Faggot” is not how Lemming sees himself, so the epithet is more of an affront to his talents and towering self-regard than his sexual preference. Jesse Williams, rotating between baseball stockings, Club Monaco-core, and nothing at all, plays him smug and almost inscrutable, less convincing as a gay man than as a rich one. When Lemming’s gay accountant Mason Marzac suggests he donate some of his fortune to charity, Lemming considers it like a trick question and elects to champion “fucked-up kids under ten.” He is not a character in whom fellow outcasts in the audience are meant to identify but more an engine of plot. And yet this clarifies one of Greenberg’s points: that the gay athlete, as he exists in the public imagination, becomes a sort of figurehead, revealing more about us than himself.

The same could be said of baseball, which in the works of postmodernists like Bernard Malamud and Don DeLillo becomes a useful shorthand for America’s investment in its own mythology, and for the merger of order and play. Baseball, Walt Whitman once wrote, “belongs as much to our institutions, fits into them as significantly, as our constitution's laws.” But, as with the constitution, not everyone fits into baseball. So when the fumbling Marzac (Jesse Tyler Ferguson, the show’s standout) is first hired to manage Lemming’s finances, he knows nothing of the sport or even his new client, recognizing him only from the marshmallow spread Lemming hawks on television. (“Yeah, that’s where my spot runs these days,” quips Lemming, after Marzac reveals where he lives. “Chelsea at around two in the morning.”) But he is made a convert — or maybe he just has a crush, or probably both — and comes to take a sincere and radical pleasure in the game’s symmetries and ceremonies, declaring baseball, in a winning first-act monologue that doubles as his initiation into fandom, “a perfect metaphor for hope in a democratic society.” And by actually acknowledging loss, he adds, to the delight of a liberal audience unhappy with the current state of the union, “baseball achieves the tragic vision democracy evades.”

For Greenberg, the gay athlete, as he exists in the public imagination, becomes a sort of figurehead, revealing more about us than himself.

Tragedy comes, in a jarring and possibly unintentional act of aggression on the baseball diamond, where all the hostility and insecurity festering in the locker room has runneth over. By this point the nudity has ceased to shock; the audience is forced to reconcile with it as the characters are their now fragile senses of self and manhood. And though the Empires go on to win the championship, sport functions as an escape only for Marzac, the novice turned enthusiast. One could interpret his happy ending as an endorsement of the virtues of representation: seeing Lemming in the outfield, Marzac finally sees himself, and the possibility for a fuller life. But that is too easy. As Greenberg’s characters, naked and then uniformed, navigate the collapsing boundaries between private and public lives, some do find salvation; others shrink. And for us, it’s merely sport.

Jake Nevins is a writer and reporter living in Brooklyn.