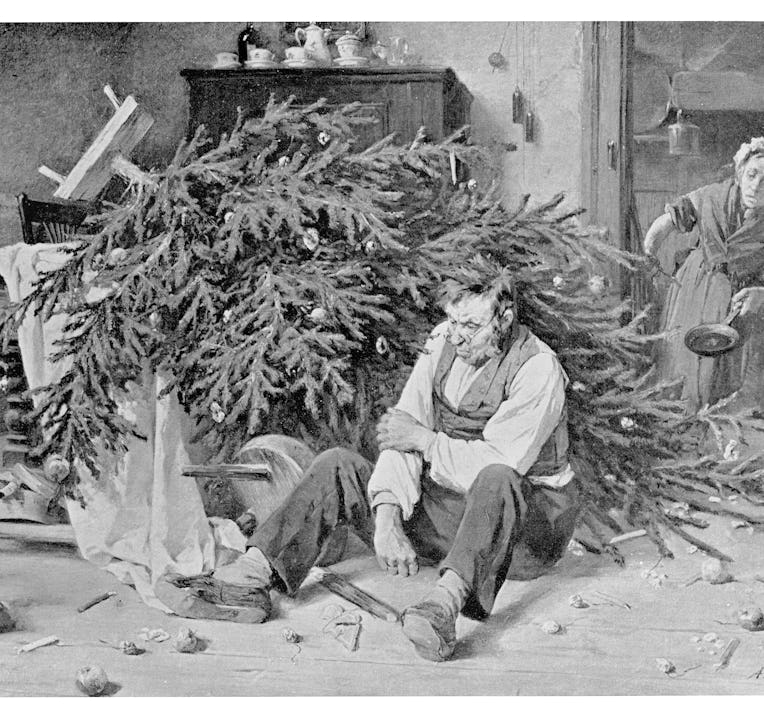

Ever since “Die Hard is actually a Christmas film!” became the most boring opinion it’s possible to express, it can feel a little glib pointing out when something we wouldn’t typically think of as a “Christmas film” is set on or near December 25. But as a fictional setting, it’s rarely incidental, bringing with it a visual language and a set of ironies ready to be exploited. The defining feature of Christmas misery is its use of juxtaposition: the gap between a sentimental idea of what the holiday ought to be and a darker reality of violence, abjection, despair, loneliness, and annihilating boredom. To be miserable at Christmas is to find yourself at odds with the world, or so these stories tell us.

The last few months have been a bountiful time for this sort of thing, seeing the release of a range of texts which portray a season that falls short of our heartbreakingly reasonable expectations. Spencer follows Diana (Kristen Stewart) as she struggles to survive a claustrophobic visit with the royal family, beginning on Christmas Eve and ending on Boxing Day. It captures the claustrophobia of family life, the exhaustion of enforced fun, and the universally relatable experience of being hassled by your family’s orderlies to come downstairs for sandwiches. Every moment of solitude Diana gets is interrupted by a demand on her attention; she is hunted everywhere and oppressed by the obligation to participate. This Christmas, when I’ve been vaping on the toilet for forty minutes and my mum gingerly knocks on the door to ask if I’d like to play Pictionary, I will be thinking of Kristen Stewart.

Crossroads (2021), Jonathan Franzen’s blockbuster sixth novel, is mostly set on December 23, 1973, and I would argue that its greatest theme, above religion, morality or “the ’70s,” is Christmas itself. The holiday is portrayed, for the most part, as dismal and dreary: a nursing home bears “mingling smells of holiday pine wreaths and geriatric feces”; a Christmas tree is “artificial, its needles silver, not even fake green”; and for Marion, a vicar’s wife, “It wasn’t clear [...] if the charm of Christmas lights at night was enough to offset how ugly the hardware looked in daylight hours, of which there were many. Nor was it clear that the excitement of Christmas for children was enough to make up for the disenchanted drudgery of it in their adult years, of which there were likewise many.” Marvel’s new series, Hawkeye, while not being very good, is attuned to the season’s particular agonies: Consider Jeremy Renner’s weary, crumpled face as he’s forced to watch a terrible Broadway musical with his family. In Ridley Scott’s House of Gucci, Christmas sets the stage for the disintegration of Maurizio and Patrizia Gucci’s marriage, culminating in an excruciating scene where Maurizio (Adam Driver) presents Patrizia (Lady Gaga) with a gift voucher for a store at which she never shops. While varying in quality, they all reckon with a fundamental truth: Christmas is a sad season.

Even much of what we think of as more traditional Christmas fare is powered by profound sorrow. While annoying to say, it’s true that A Christmas Carol is “really a story about trauma,” while It’s a Wonderful Life portrays — and ultimately endorses — the necessity of relinquishing your dreams in the face of adult responsibility. Wham’s “Last Christmas” is similarly dark — a fact often obscured by its glossy production and status as a karaoke classic. Really, it’s quite bleak; a study in wounded self-deception. The narrator, despite his insistence to the contrary, is clearly nowhere close to being over his ex. “If you kissed me now, you’d only fool me again,” reads as more hopeful than defiant, while the “real love” he claims to have found is a consolation prize, and not a very consoling one at that (if it were otherwise, wouldn’t he be singing a song about them?). Unlike Scrooge, the narrator of “Last Christmas” is offered no redemptive ending. As the song fades out, against the whispered promise of “maybe next year…’” he’s as trapped by his own resentment and yearning as ever — and I love it!

Perhaps my affection for this genre is because British soap operas reach a crescendo of misery at Christmas. It’s when we see the climax of whatever torrid storylines have been gathering momentum in the months before, which usually involve: death; divorce; murder; adultery; alcoholism; explosions — both planned and accidental; people arriving unexpectedly and leaving in disgrace. I watched a lot of these holiday specials when I was young, long before I was engaging with anything else that wasn’t strictly aimed at children. Suffused with heartbreak and despair, they taught me as much about the meaning of Christmas as Sunday school or The Muppet Christmas Carol ever did. Despite the fact that they weren’t especially glamorous, I always found the misery they depicted aspirational, and, to some extent, still do. Pausing in the snow for one last pensive look around a cobbled street before you leave forever; downing vodka straight from the bottle as the lights from a Christmas tree twinkle behind you — even now, I can hardly think of anything more festive.

***

I don’t believe there are many people for whom Christmas is an uncomplicatedly happy time; most of us know what it’s like to suffer and grieve against the merriment of the world at large. There’s also an inevitable kind of melancholy baked into the season from early on. “There is nothing sadder in this world than to awake Christmas morning and not be a child,” the humorist Erma Bombeck once wrote. There’s a kernel of truth to this, but the process of disillusionment she’s referring to begins in childhood itself. Most people are quite young when Christmas comes around and no longer feels the way that it did before. When this happened to me, it was my first introduction to the knowledge that certain qualities of feeling can leave us and never return. But if Christmas is disappointing every year — as it has been since I was nine — how can it still continue to be disappointing? In fact, I think the opposite might be true: there’s satisfaction in an expectation being met.

Carson McCullers, being better known for her sad, Southern Gothic-tinged novels, wrote a series of essays about Christmas, in which the passing of time looms large. In Home for Christmas (1949), she writes of her younger self, “I was experiencing the first wonder about the mystery of time [..] would the Now I of the tree-house and the August afternoon be the same I of winter, firelight and the Christmas tree?” Because the day itself slips through your fingers so quickly, it teaches us that pleasure is a finite source, something which dissipates and leaves you feeling empty in its absence. Think of the desperate self-rationing with which children eke out their ever-dwindling pile of presents, an experience which can only be approximated in adult life by running out of drugs. “At twilight I sat on the front steps, jaded by too much pleasure, sick at the stomach and worn out,” writes McCullers. “Christmas was over. I thought of the monotony of Time ahead, unsolaced by the distant glow of paler festivals, the year that stretched before another Christmas — eternity.” The passing of time can make happiness painful to experience, and beauty painful to perceive. This is what melancholy means, to me anyway, and why it can be tied with pleasure. Even as an adult, I feel this most sharply at Christmas.

This Christmas, when I’ve been vaping on the toilet for forty minutes and my mum gingerly knocks on the door to ask if I’d like to play Pictionary, I will be thinking of Kristen Stewart.

But while the last few months have seen a flurry of texts which cater to this kind of melancholy, the dominant form of Christmas entertainment today is the unfailingly upbeat romantic comedy. Netflix’s Love Hard (2021) concerns a dating columnist who gets catfished by an incel, whom she later falls in love with, but really it’s an effort to spin a narratives out of a series of talking points from early 2010’s BuzzFeed articles: there’s a recurring debate about whether Die Hard is a Christmas movie (in a slyly feminist twist, this time it’s a woman expressing this inane opinion!) and at one point the characters perform a duet of “Baby, It’s Cold Outside,” with the lyrics updated so that they’re promoting consent.

In Single All the Way (also released by Netflix this year), a gay man brings his best friend home for Christmas in an attempt to dupe his family into thinking they’re a couple, before abandoning this ruse immediately when his mother announces she’s set him up on a blind date. The film has drawn praise for not using the characters’ sexuality as a source of conflict, but the downside is that the story doesn’t feature any conflict whatsoever — aside from their prurient obsession with his love life, the protagonist’s family are so sickly sweet that it rings hollow. As a gay man myself, I’m not above being pandered to, but you’re going to need to try a little harder than hiring Jennifer Coolidge to say the word “Grindr” if you want to elicit a chuckle out of me.

Criticizing these films for being corny is pointless, which hasn’t stopped zinger-filled deconstructions of them becoming an unfortunate seasonal tradition of their own. The cheesiness is exactly what people like about them and they’re not trying to be anything else. But the sentimentality on display never moves me, because it’s based on a view of the world which is slightly too ersatz. The lessons they impart offer me no comfort, because they have no bearing on reality. While I am a harried city slicker who returns to my provincial hometown each Christmas, I never fall in love while I’m there or quit my career for something more fulfilling; nor are any of my elderly relatives, as much as I adore them, especially sassy or prone to cracking wise. I’m not saying that Single All the Way would be better if it had featured a suicide attempt or someone becoming addicted to meth, but it would have been more up my street. The most affecting kind of Christmas sentimentality recognizes the season’s misery, and then transcends it.

Tangerine, my favourite Christmas film of recent years, follows two trans women in LA across December 24: Sin-Dee, just released from prison, is trying to track down her boyfriend, who she learns has been cheating on her with a cis woman, while Dinah is preparing for a musical performance at a bar, in which she is deeply invested and which does not go well. It’s too vivacious to be classed as wholly “miserable,” but it is filled with deep yearning, disappointment, and sadness. Towards the end, its two protagonists have a falling out upon the discovery that Dinah has slept with Sin-Dee’s boyfriend, then a group of men chuck a bottle of piss at Sin-Dee while shouting transphobic abuse. But when they visit a laundromat together to wash her soiled clothes, and Dinah gives Sin-Dee her own wig to wear while they’re waiting for Sin-Dee’s to dry, the film ends with a reconciliation that is so tender it’s almost unbearable to watch.

The “message” you could take from this is that friendship provides solace in a world which is often cold and cruel. In its own way, this is just as life-affirming as any Netflix rom-com. When I watch the end of Tangerine, I can believe that there really are consolations in life, and that love is a profound and sacred thing. And while for the rest of the year I don’t think the purpose of art is to impart uplifting moral lessons, at Christmas I make an exception.

Because I do love the season. I am a grown man who still frets about “not feeling Christmassy enough”; I have wept at a department store advertisement about a sexually frustrated penguin; I have been known to insist that God Rest ye Merry Gentleman “absolutely slaps.” I just also embrace Christmas as a festival of sentimentality, spanning the range of human emotions, and think that sadness, disappointment, and yearning deserve their rightful place. There is a whole world to explore in the space between characters on Eastenders scratching each other’s eyes out and romantic comedies where people’s relationships are perfectly harmonious and everything works out well. The gentler end of melancholy can lend the season a gravitas, acting as a counterbalance to everything about it that’s lurid and commercial. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I must serve my husband some divorce papers, get arrested for embezzlement, and burn down my flat in a chip pan fire.

James Greig writes about culture and society.