How to Make a Movie About a Mass Shooter

Peter Bogdanovich's 'Targets' is more than an early career curiosity

You begin at the ending: Boris Karloff in a collapsing, flooding castle, living out the final act of some unknown tragedy. Watching this movie, along with us, are its crew and its star — Byron Orlock (played by Karloff). Orlock has had it with starring in B-movies; he’s going to retire. This is bad news for screenwriter Sammy (Peter Bogdanovich), who has finally gotten permission from the studio to direct one of his scripts if he can just get Orlock to sign on. As Orlock leaves, Sammy chases him outside to talk him out of his decision.

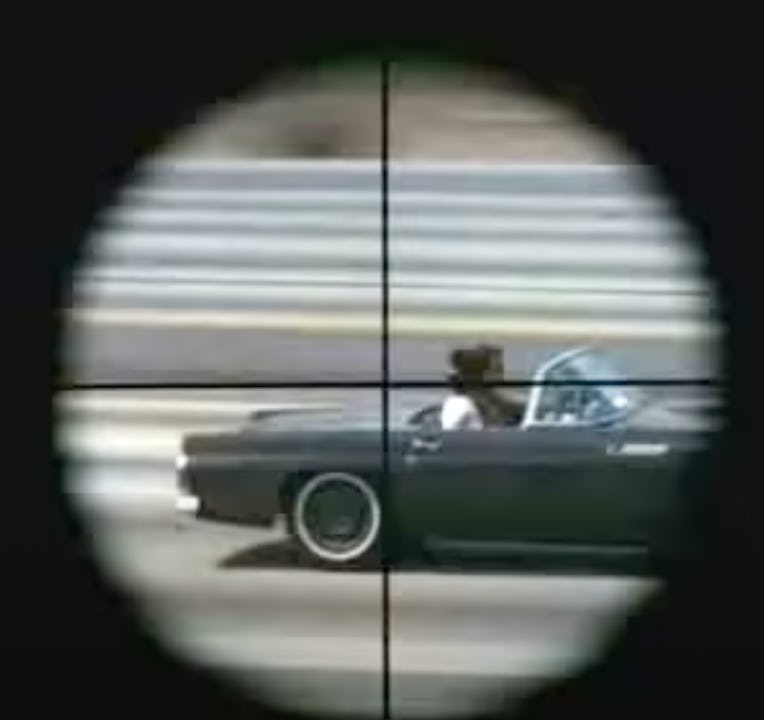

These are the opening minutes of Peter Bogdanovich’s debut film, Targets (1968). At this point, you comfortably know what kind of movie you’re watching: it’s a movie about making movies, the waning of the old and the rise of the young. But as Orlock and Sammy argue, the crosshairs of a gun slide over the horror star’s face. There’s still another movie here.

We now meet clean-cut, square-jawed Bobby Thompson (Tim O’Kelly), an insurance agent and gun enthusiast, who is out shopping. He’s always wanted, he remarks to the salesman, a gun like this one. As will be reiterated later in the movie, gun safety’s first rule is that you don’t point guns at people. But Bobby knows guns and knows the rules and we will watch him follow his own version of this rule: don’t point a gun at something you don’t want to kill. Not yet, though. He’s just testing the gun.

***

When, in 1966, Charles Whitman, aged 25, killed his mother and then his wife, tucked them into bed, and ascended the University of Texas’s clock tower to open fire on the populace below for an hour and a half, his actions did not yet constitute a genre. Even now, when mass shootings are regular enough to have their own conventions and cliches, what Whitman did remains unusual: there aren’t that many snipers. (The Beltway sniper and the Vegas sniper are the two you can probably name.) Of course it is no great consolation to suffer and die at the hands of an original.

In a press conference after Whitman died, Heatley Charlie, a psychiatrist with whom he’d had a brief consultation months before, gave him the epithet that would become his eternal description: “all-American boy.” Next to the stories about how very, very normal Whitman was were the ones about how maybe he wasn’t so normal. He had been making references to climbing the tower and shooting out of it for years, including in a session with that very psychiatrist. There were facts of Whitman’s biography that conformed with a cheery normalcy: he’d been the youngest Eagle Scout in the world. There were ones that didn’t: he grew up with a violent father who once almost drowned him. He had been convinced he had a growth in his brain, and as it turns out, he was right.

Some arrangement of these facts, or facts like them, should produce an answer as to how this kind of event could happen. But they don’t. There’s no consensus that the tumor in his brain had anything to do with his behavior; people respond to their violent upbringings in all kinds of ways, including modeling themselves on whatever it means to be the opposite of their parents, and the evidence indicates that this what Whitman tried, with varying degrees of success, to do. Sometimes the only way to understand something horrible is to know you can’t. “It's neither here nor there. It's done. It's over with; it's gone,” Whitman’s father-in-law once said. “There’s no use trying to find out why.… I got my consolement from Almighty God. I kind of left it in his hands. That's the only way to live a decent life.”

Faced with a blank, we want to fill it in. Mass shootings are not, in themselves, narratively satisfying, and present problems unique to them. There’s too much disjuncture, the relationship between what will happen and what has is too unclear. Long after their heyday, serial killers continue to fascinate on the screen because they create their own narrative stakes through their romance with the police on the one hand, their victims on the other, and this lets the violence exist within a kind of relationship, however perverse. But a spree killer or a mass shooter can’t generate such a relationship. Still, such a person is not a natural disaster, either, and treating them like one isn’t very satisfying. What to do?

A film like Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011), in which the titular Kevin shoots up his school with a bow and arrows, addresses this in part by fracturing time around the event, taking place before, during, after. But while the movie is beautiful and moving, taken straight it requires believing our killer was evil from the cradle, taken slant is about an abusive mother as much as a mass shooting, and taken either way is much more about the relationship between a mother and her son than the spree killing. Two-Minute Warning (1976), a clearly Whitman-inspired film about a sniper at a football game, uses the convention that would become beloved of the slasher movie later: follow a mix of beautiful people and losers, let us know they have some manner of dream, and then pick them off one by one. The Deadly Tower (1975), a TV movie directly about Whitman, makes him into an almost silent, lumbering monster, and invests the drama in Ramiro Martinez, a hero cop (and real person) who goes above and beyond the call of duty to take Whitman down, all despite being a victim of racism within his department.

The quality of these movies varies wildly — We Need to Talk About Kevin is a great film, Two-Minute Warning is watchable but inert, The Deadly Tower exists — but none of them approach the dramatic problem of mass shooting as directly as Targets, which, rather than attempting to set up a single narrative that can involve a mass shooting and its victims, doesn’t even try. Instead there are two movies, different in their tones, different in their color schemes, different in their concerns, which are set to collide by pure accident. It captures what makes spree killing both personally frightening and narratively disruptive: you will be killed because you’re there, and no other reason.

That Orlock’s side of the story is about his personal unhappiness with his career underscores this. He’s an old man evaluating his life, but the specter of death that hangs over him has nothing to do with this process. No result would have any effect on a bullet in his head. Nor will it respect if the process is not over.

***

Probably nobody starts out to make a movie that’s really three movies stitched together, but sometimes, accidents work out in your favor. Much of Targets’s odd structure comes down to the circumstances of its creation. Boris Karloff had made a movie for producer Roger Corman called The Terror, but Corman realized that Karloff was still on the hook for two days’ worth of filming. Corman, whose movie studio allowed a lot of young directors to get their start, offered the Karloff project to an ambitious young Peter Bogdanovich, on the condition he’d also do some work on a movie eventually called Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women, and work in some of the footage from The Terror.

Bogdanovich, along with his then-wife Polly Platt, hit on the idea of using the preexisting footage as a film-within-a-film early in the process. They toyed with making a film in which Karloff played an actor–serial killer, but then Platt, as Bogdanovich recalled, “said that we should have a modern killer. We both decided that the most modern, terrifying murderer — modern horror — was the sniper in Texas.” And with that, they had their movie.

It captures what makes spree killing both personally frightening and narratively disruptive: you will be killed because you’re there, and no other reason.

Targets, coming as it does at the close of the 1960s, can in retrospect be understood as movie about what was going to happen to horror. The time of Karloff’s swoony, gothic horror had already passed away. “You know what they call my films today? Camp. High camp.… I want to show you something,” Orlock says to Sammy, tossing down a newspaper that reads “YOUTH KILLS SIX IN SUPERMARKET.” “My kind of horror isn't horror.… No one’s afraid of a painted monster.” The clips we see of “Orlock’s” movies (all real Karloff films) are films in which, even if we don’t know the plot, we can tell that the people have ordinary human motivations: love, revenge. A movie like Psycho, eight years earlier, had had a tacked-on explanation for Norman Bates’s killing. But horror, in films like Black Christmas (1974) and Halloween (1978) was about to shift toward killers whose power to scare derived from how they had no discernible motivation at all.

So what’s wrong with Bobby? We know from the first moment that something certainly is, but in his life, he has it all, even more than Charles Whitman did: a job he’s good at, a beautiful wife, and loving parents. They all live in the same home, which is made up as a kind of cold, washed-out doll house of blues and grays (even their paper towels are blue).

One achievement of Targets is that Bobby never feels cool. Even before the shooting starts, his sequences are uncomfortable, lacking any of the warmth and charm of the characters of the other half of the movie. His tastes are childish: he eats candy bars, drinks soda pop, and takes a break from his killing spree to eat a sandwich he brought along that looks like his mother packed it for him. In short, he’s kind of a dork, and nothing about that changes once he becomes a murderer. And he is careless, losing guns and ammo through accidents he could have easily avoided. But of course he doesn’t have to be good at anything but shooting to kill a lot of people.

After killing his family and an unlucky delivery boy, Bobby first kills drivers along a highway, then goes to a drive-in theater playing Orlock’s new movie, where he picks off the viewers. At the drive-in theater, isolated and vulnerable in their individual cars with speakers playing the movie, the audience cannot hear him shooting or notice what’s happening until it’s too late. When some wounded try to warn the others, people open the doors of their cars, the internal light flips on, and Bobby kills them.

We can see the panic slowly spread among the cars, but many others remain oblivious: Orlock jokes that people are leaving because they don’t like the picture. Then his assistant gets shot. So he goes to deal with this situation — one monster to another.

***

Here’s how Targets ends: Orlock manages to reach Bobby and slaps him across the face, and the younger man instantly collapses. When I first watched the movie, I burst out laughing at this moment, because the sudden release of tension was so overwhelming. But Bobby is also simply laughable, even if his killing isn’t. He doesn’t deserve a big standoff, he gets no great cause, and though Orlock asks himself, “is that what I was afraid of?” as Bobby is taken away by police, he performs no important narrative role in terms of Orlock’s own story, which is not resolved at the end of the movie.

There’s an old idea that evil is the absence of what’s good, not any particular thing itself. In some ways, Targets is one of the best movies I know of to illustrate that premise. Bobby’s world, drained of color and of warmth, of food that isn’t sugary-sweet, of any pleasure but guns, is a world without anything in it, and he is a person without anything in him. His violence is more real than one of Orlock’s Gothic monsters, but he is less, because he commits his acts not out of grand passions or hungers but out of, essentially, boredom. The rich and human world of the other half of the movie, where people fall in love, drink too much, argue, and joke, is simply more world than Bobby’s. There is more there. People want things, and regret them.

If the mass shooter is a narrative problem in the way other killer archetypes of the past were not, it also presents new possibilities. Serial killers in fiction are geniuses; they are charismatic, philosophical, cultured, unusually discerning. But a mass shooter can be what a killer really is, in real life: pathetic. Inert, uninteresting, unable to generate anything, unwilling to participate in the business of living, the mass shooter attempts to write his name with blood. But the signifier is empty.

Peter Bogdanovich, who died this month, will be better remembered for other movies, and Targets will continue to be mostly a curiosity in his career. But Targets deserves to be rewatched and appreciated in an age where its subject is now almost cliche, not just as Bogdanovich’s first movie, but as a piece of art that tackled, successfully, a subject that is still elusive now. Targets is not sentimental, it is unsparing in its depiction of the effects of deadly violence, but it understands that something beats nothing, every time.

B.D. McClay is an essayist and critic.