‘For All Mankind’ Is a Cold War Dad’s Dream

Apple TV’s counterfactual history gets at something true about American empire

For All Mankind, currently airing on Apple TV+, is a show about NASA at the height of the space race. All the perennial tropes of the genre are on display: square-jawed astronauts undergoing training; bespectacled engineers calculating distances with protractors; raucous cheering breaking out in mission control as the latest crisis is averted. At first glance, the show can look like a nostalgia piece. A soothing glass of Tang for aging Boomers, say. Co-created by Ronald D. Moore, of BattleStar Galactica fame, alongside Matt Wolpert and Ben Nedivi, the show presents a counterfactual version of the US over the last 50 years, one where the space race never left the headlines. Astronauts trade jokes with Johnny Carson; rocket launches are prime-time events well into the 1980s. But the show is far more than a vision board of lovingly-curated period details. Now in its third season, For All Mankind crafts a dark, even cynical look at what motivates American society, and what leaves it cold.

Counterfactual stories, or alternate histories, build their worlds out of hinge points: Decisive junctures where history could have just as easily gone one way or another. For All Mankind begins with a doozy. It’s July 1969, and everyone in America is glued to their televisions, watching the moon landing. Live, in black-and-white, an astronaut steps out of the landing module and onto the lunar surface. He opens his reflective visor, looks into the camera, and begins to speak . . . in Russian! Praising the Marxist-Leninist way of life! Planting a hammer-and-sickle flag on the moon! The Soviet Union, and not the US, makes it there first.

Everyone in the US, from housewives to NASA engineers to President Richard Nixon, goes apoplectic. The moon is meant for the god-fearing capitalists of the US of A, not the godless commies of Mother Russia. Congressional committees are convened. Budgets are doubled, tripled. Overnight, the moon becomes the latest front of the Cold War. Rather than fade into the background, the Space Age comes to the forefront of American life, rubbing elbows with the other pressing issues of the day, from Vietnam to women’s rights. Indeed, when NASA does manage to land its own module on the moon in 1971, the first astronaut to step out of it and onto the surface is a woman.

In many ways, fighting the Cold War in space results in positive benefits for this alternate society. In a storyline from the first season, some backdoor-dealing that involves granting lucrative NASA contracts to individual states leads to the national ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment in the early ’70s. Phyllis Schlafly, who helped torpedo the ERA in our own timeline, stands no chance of going against the All-American Astronauts. The space program is a rising tide that lifts all boats.

But what does that say about American society? That we rise to our best when, and only when, we have an outsized foe to compete against? That lacking world-historical competition of the sort provided by the Soviet Union causes us to grow lazy and complacent?

***

Ross Douthat’s 2020 book The Decadent Society offers, like all of his work, insights that are half-perceptive, half-fearful projection. When he describes society as “decadent,” he doesn’t primarily mean it in the Rome-is-burning, Caligula’s Coke Party sense. (Though that is there — Douthat never met a pleasure he couldn’t pathologize.) He means decadent in the sense of “exhausted,” culture having run out of original ideas, instead shambling forward on the fumes of earlier triumphs. There’s convincing evidence for such a charge. To be a sentient human in the 21st century is to witness a stunning lack of imagination in nearly every sphere, from government to entertainment to, I don’t know, highway maintenance? Endless reboots of superheroes and Star Warses; politicians yearning to return to 1992; politicians yearning to return to 1932. You name it, it sucks.

Douthat locates the origin of this decadent stagnation in 1969. But he’s not thinking of the Summer of Love. He means the moon landing. After expanding westward as far as physically possible, after emerging from World War II as the dominant superpower, the restless US made a bid for the last frontier left. And it found — nothing. Just rocks and dust, which barely hold up the American flag planted in the airless surface. With no frontier left to conquer, the country resigned itself to replaying its greatest hits endlessly.

But the moon of For All Mankind makes for a far more satisfying frontier, precisely because it has to be fought over. The show acknowledges this explicitly. After landing their own module, NASA takes the next logical step and establishes a base on the moon, naming it Jamestown after the first English settlement in what’s now known as Virginia. Colonization 2.0! A three-person team works there initially, mining ice crystals from deep within a crater. Gordo Stevens (played by Michael Dorman), one of the astronauts, describes their mission as “homesteading,” like the pioneers of the Midwest back in the 19th century. He says this with disdain, as the isolation soon gets to him, precipitating a mental break.

But the Americans aren’t alone up there. The Russians establish their own lunar base, on the edge of the same crater, to excavate the same minerals. “Cowboys and Indians,” as Commander Ed Baldwin (Joel Kinnaman) describes the situation. Which is absurd — the Russians are no more indigenous to the moon than the Americans. But in terms of carrying the logic of the frontier into space, it makes a grim kind of sense. Territorial expansion, whether on the earth or the moon, has always involved reclaiming, with violence, the territory from those already living there. Casting the Russians in this role allows those expansionist impulses to continue unabated.

And violence does indeed break out. Season 2 sees the Russians usurp the mining site the Americans have claimed. (Claim-jumping, land rights — the grammar of the Wild West plays out in space, with new names swapped in.) Incensed, NASA sends a platoon of Marines to the moon as a security force. Their rifles are painted white, to keep from overheating in the harsh climate. When, inevitably, an American shoots and kills a Russian on the soundless lunar surface, the Russians respond in kind. There’s an incredible scene where a Russian cosmonaut stands on the lunar surface, rifle in hand, aiming at the window of the Jamestown base. His stance is that of a sniper in Vietnam, or a rifleman at the OK Corral. He fires, shattering the window, causing the base to depressurize violently. An astronaut, suitless, gets sucked through the shattered window and flung onto the surface. Old forms of violence leading to new ways to die.

***

I’m a father, and therefore I am contractually obligated to develop an unaccountable fascination for some kind of war. WWII did the trick for decades. Men all across this great land built model airplanes in garages and memorized the names of submarine models. Being an elder millennial, though, I just missed the cutoff to become, as they say, a buff. Instead, another conflict drew my attention. I have become a Cold War Dad.

Central to being a Cold War Dad is the recognition that the US is not some benevolent actor, sowing peace and democracy across the globe. The country pursues its own interests ruthlessly, even maliciously, happy to overthrow governments and install dictatorships as the spirit dictates. To be included in my Cold War Dad canon, a given work must take a jaundiced eye at the workings of American power. Don DeLillo’s Libra ranks high on the list, as does James Ellroy’s Underworld U.S.A. trilogy. John Le Carre’s Smiley novels, which hold that waging the Cold War invariably corrodes one’s soul, have pride of place as well.

For All Mankind, then, is a must-see for Cold War Dads everywhere, no matter their gender. By recasting the space race from a story of Boomer triumphalism into a clear-eyed account of Cold War antagonism, the show — if you’ll forgive the pun — brings these American heroes down to earth. Seen in such a light, even the very title is ironic. “We came in peace for all mankind,” reads the plaque affixed to the first lunar module. Maybe. But what keeps humanity coming back is the cycle of antagonism, of competition — of war.

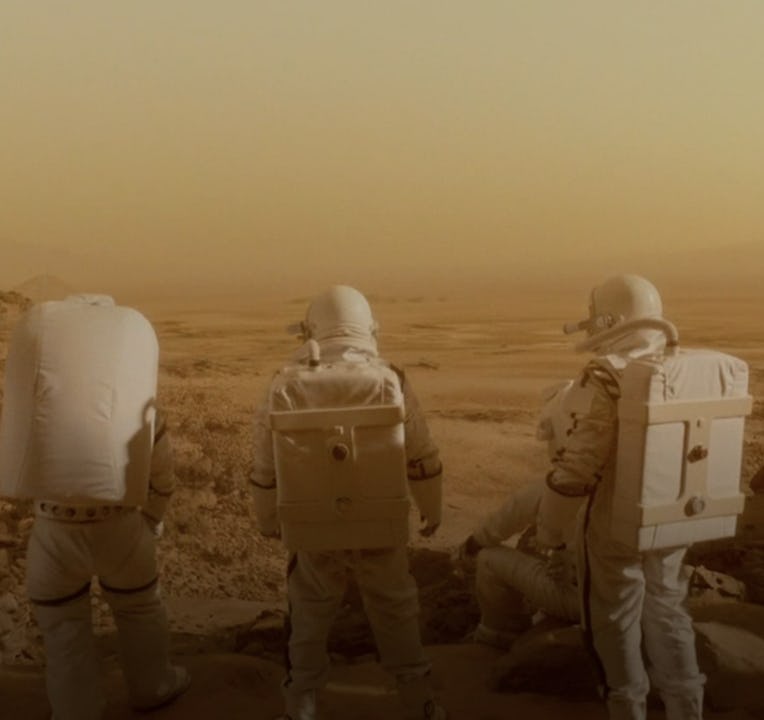

For All Mankind is currently in its third season, which sees the US and Russia heading for Mars. There’s another competitor, too. A private enterprise named Helios launches its own mission to Mars. Helios is led by a charismatic mogul named Dev Ayesa, very much in the vein of oligarchs like Musk or Thiel. Perhaps companies will snatch the baton of colonization from the hands of countries. The forces of capitalism, which the Soviet Union has tried to withstand and the US has tried to wield, may break free of national boundaries entirely, loyal to no one. That’s the thing about the Cold War: no one wins, and it never ends.

Adam Fleming Petty is the author of a novella, Followers. His essays have appeared in the Paris Review Daily, Electric Literature, Vulture, and other outlets. He lives in Grand Rapids, Michigan.