England Is a Trans Horror Story

Alison Rumfitt's new novel captures a nation in all its haunted shittiness

Every now and then, a journalistic article will be written which attempts to figure out why Britain — a small, damp island on the eastern edge of the Atlantic — is so full of “trans-exclusionary radical feminists,” or TERFs. Granted, this is also a place whose inhabitants, especially the ones who call themselves English, are given to doing things like throwing yogurt over themselves to make it look like they’ve been attacked by milkshake-wielding anti-fascists; forming internet communities adulating some mythic golden age when the bin men carried proper metal bins and the whole street would pool together to buy them a turkey every Christmas and you’d give them the keys to your house; and kissing their shirtless buddies on the lips before they hit them with chairs. But even against the background of all this other stuff, the TERF thing still manages to stand out.

While trans people, sadly, continue to face all sorts of barriers to their liberation pretty much everywhere in the world, there is something about Britain which has produced in its people a sort of morbid, obsessive fixation on trans rights, far beyond any common or garden bigoted norm. In Britain, the question of trans rights has repeatedly sent public figures, even or perhaps especially ones who would previously have considered themselves “a bit of a leftie,” completely and indeed irreversibly insane.

Every now and then, TERF brain will claim another Brit: from once-beloved comedy writers, to wildly successful authors, to chat show hosts I had mostly forgotten existed until they got merked on Twitter. These people will start out “just asking questions,” or hand-wringing about the rudeness of the trolls online, until just a few short months later they have wound up all their other creative endeavours to devote themselves full-time to posting about ladies’ bathrooms. Inevitably they find themselves “cancelled” — precipitating several weeks in which they are able to promote their latest book, You Can’t Even Say ‘Susan’ Anymore: The Great Trans Conspiracy To Stop You From Using Your Own Name as an immovable fixture in the Sunday papers, and perhaps even on morning TV.

Just what is going on here? The articles I’ve mentioned cite factors including the prominence of former members of the “UK Skeptics” movement in British print media; the role of the parenting forum Mumsnet in radicalizing lonely, isolated middle-class women; and the ways in which the UK’s unwillingness to grapple with its imperial past have cut white middle-class feminists off from intersectional critique.

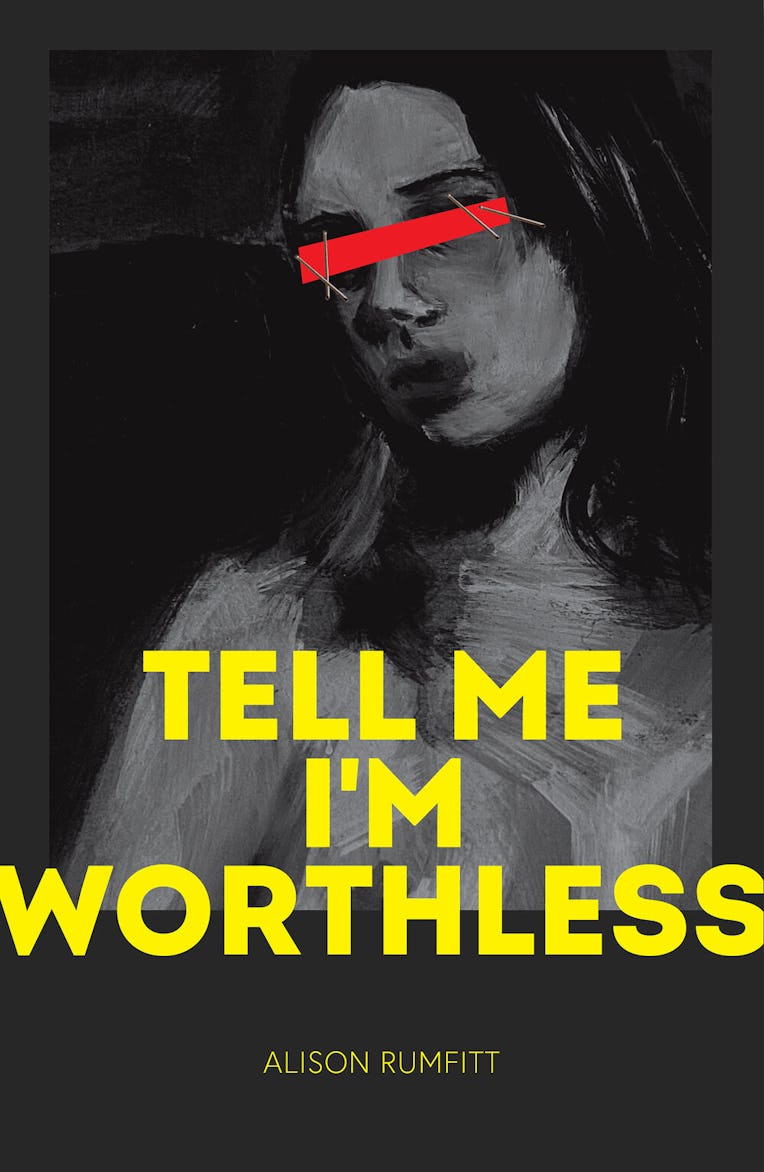

But for Alison Rumfitt, self-described “semi-professional trans woman” and author of the breakout small-press horror hit Tell Me I’m Worthless, these explanations miss something: “something,” she told me when I talked to her on Zoom the other day, “that I couldn’t put into words.” And this was in fact, she told me, why she wrote her book. Rumfitt wanted to give a different sort of answer to the question, “Why is Britain so full of TERFs?” — the kind of answer that only really makes sense if given an aesthetic presentation.

“Maybe the problem is Mumsnet or the media or the way British feminism has developed or something like that. But maybe it’s that there’s a dead giant buried under a house somewhere near Brighton.”

Tell Me I’m Worthless has largely been billed as a work of “trans horror”: a horror novel by a trans woman, featuring a number of trans characters, that satirizes transphobic political activists while also playing on specifically trans forms of insecurity, self-loathing, and fear. It is this. But it is also, perhaps indeed primarily, a book about England (not just Britain but England) — about the England of lads-chair-hit-kissing and oldey-timey binmen-loving and dairy-based self-mutilation and Captain Tom adulation and Jeremy Corbyn not bowing enough at the cenotaph and David Cameron fucking a pig. The England that I, cis man, also grew up in: the England I know is bad, but whose badness I feel uncannily fond of; the England I have tried to live outside of but simply miss too much when I’m gone; the England that I am, perhaps against my better judgement, raising my kids in; the England that endlessly fascinates me, this thing that I belong to, but will almost certainly never be able to fully, transparently comprehend.

Tell Me I’m Worthless is the best book to come out of England this year, and it is the best book about England in 2021 that has been, perhaps ever could be, written.

“Why write a book about England,” I asked Rumfitt, “that’s also a trans horror story?” “Well, isn’t it obvious?” she replies. “England is a trans horror story!”

Tell Me I’m Worthless is the sort of book that’s structured around sudden bursts of terrible, startling imagery and disorienting narrative revelations, so in a way it’s hard to write about it without giving too much away: you just have to read it. But in short, it tells us about what happened when, one night, three girls — Alice, Ila, and Hannah — snuck into a haunted house called Albion, and effectively freebased England itself. Three years later, Alice, who is trans, ekes out a living livestreaming herself doing housework and recording “sissy hypno” videos for men on the internet while being haunted through a poster by the eyeless ghost of a singer who may or may not be Morrissey. Ila — who believes that, in the house, Alice raped her — has become a prominent TERF activist. Hannah, meanwhile, has not been seen since, unless you count her face trying to emerge from Alice’s walls.

Tell Me I’m Worthless is the best book to come out of England this year.

In Tell Me I’m Worthless, England manifests itself in at least two ways — ways which initially seem distinct, but which are in fact quite indelibly linked. In the house of Albion, England appears as an unbearably bright light, in which everyone is shown as their worst self: a light which channels hate towards weakness, which picks out the ways any specific individual is marginalized and makes that a target for violence. But outside of the house, it appears as the everyday English void of damp flats; circuitous suburban bus routes; phallic war memorials by the sea front; crappiness and despair. In Tell Me I’m Worthless, Rumfitt maps a geography of crappiness, the physical manifestations of which are in no sense separable from the online world which exists both above and around it: the closed little pockets of private hate which Alice and Ila, in their respective ways, both fall foul of and find comfort in.

This is the nation described by Alex Niven in his 2019 book New Model England as not actually existing: by which he means, that in contrast to say Scotland, or Wales, or America, or Russia, England has no real, positive existence. England — for Niven, as for Rumfitt — exists only as something to haunt the English: the ghosts of the Norman Conquest; the Harrying of the North; the failed English Revolution; the sins of Empire. For Niven, the nation primarily manifests itself through the notions of “historical curse,” “containment,” “hiddenness and void.” In Tell Me I’m Worthless, we see England just as Niven did in his book: as a nothing, a lack, that is at the same time a sense of being confined — a country of great looming, empty spaces, in which there is nevertheless “no more room.”

Whatever way you look at it, then, England is a haunted house. For me — as for Niven, as for Rumfitt — England, ultimately, is home. But it is a strange sort of home, an uncanny home; a home where you can never quite feel comfortable, but from which there can be no escape. Indeed, a big part of the power of Rumfitt’s Albion is that it exists not just as a place but as a mark, a scar, a stain. When you leave it, the haunted house remains with you; when you enter it, you were already there. Probably the feeling I have towards Tell Me I’m Worthless is at least in some sense analogous to the feeling the great patriots of other, “real” nations get when they well up at some heartening patriotic poetry or something.

You can tell a lot about a nation, I think, by what sort of genre fiction is most apt for it: from the Western to the Scandinavian Noir. Britishness, for its part, is most meaningfully poeticised in the melancholy spy novels of John Le Carré, those dingy epics of damaged men on the edges of the ruling classes, endlessly striving to hone themselves down to the point where they can happily become an instrument for the blind forces of global power which play just above their heads. But Englishness has typically been portrayed most honestly in horror fiction, fairy stories; weird tales.

In this, Rumfitt is most obviously the heir to the likes of Daphne Du Maurier, Angela Carter, and M.R. James — as well as The Fall’s Mark E. Smith. But nowadays, Rumfitt aside, the people who most obviously seem to have their fingers on the pulse of “what England means” are extremely online outsider artists like Dan Douglas, who is currently in the process of obsessively recreating contemporary England using a level editor for the mid-90s Doom-like video game Duke Nukem 3D, or Trevor Bastard, whose ‘Extended Universe’ of twitter accounts has lawyers posting about euthanizing their dogs to give them enough time to fight Brexit, while referees at non-league football matches are immolated by hot air balloons that have crashed into the pitch. It is in combining that shitposting approach to Englishness with the horror/weird tales tradition that Rumfitt manages to paint such a dazzling vision of the shitpost England of today: a nation where everything just seems to constantly get stupider and stupider; worse and worse.

In one scene from Tell Me I’m Worthless, a ghost appears covered in three years’ worth of human piss and shit. A few days after I talk to Rumfitt, I see a video of a flash mob in which a group of ‘gender critical activists’, dressed up as witches, are putting some sort of protective hex over the women’s toilets with their brooms. Some artists, I think to myself, really do just have the pulse of reality running through them.

In any functioning country, Rumfitt would be immediately understood and heralded as the voice of her nation. But of course, England is not a functioning country — no more than Britain is. Then again if it was, we would neither need, nor have, Alison Rumfitt. Perhaps in the end Tell Me I’m Worthless can never do any more than briefly illuminate the English void: a brilliant scream. But if you even want to attempt to understand Why English People Are Like That, then it really is essential that you read this book.

Tom Whyman is a philosopher and writer who lives in the North East of England. His first book, Infinitely Full of Hope: Fatherhood and the Future in an Age of Crisis and Disaster was published earlier this year.