What is a novel? Towards the end of Either/Or, the narrator Selin offers a theory: a novel is “a plane where you could finally juxtapose all the different people, meditating between them and weighing their views.” By the time readers get to that point in Elif Batuman’s second novel, it doesn’t feel like a navel-gazing question.

Batuman, in a 2006 essay for N+1, offered another definition: “A novel says ‘I looked for x and found a, b, c, g, q, r, and w.’ A novel consists of all the irrelevant garbage, the effort to redeem that garbage, to integrate it into Life Itself, to redraw the boundaries of Life Itself.”

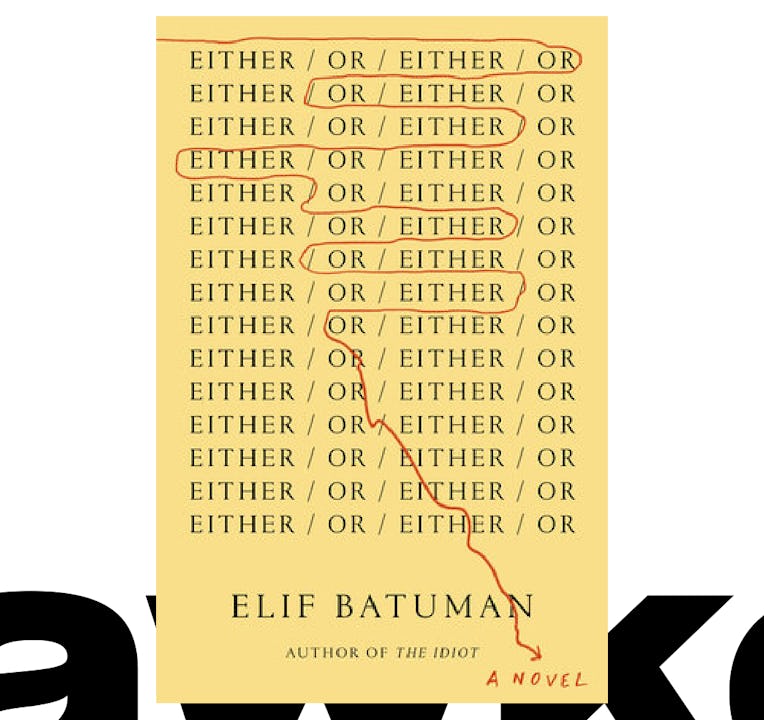

Either/Or picks up where Batuman left off her previous novel, The Idiot. That book, which was exceptional, very popular, and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, tracked Selin’s freshman year of college at Harvard. It centered on her tumultuous relationship with Ivan, an older student. Either/Or covers Selin’s sophomore year. Ivan is still an occasional obsession but never appears in person. Without the conventional will-they-or-won’t-they pull to drive the narrative, we are left with a question: what, exactly, are we doing here?

Selin’s theory, combined with Batuman’s, is a pretty good answer. Batuman imbues Selin with an absurd level of insight and clarity about the people and events around her. The running monologue is refined and improved from The Idiot, indicative perhaps of Selin’s growth as she progresses through college. The great joy of Either/Or is reading as Selin considers whether what people are saying to her makes any sense or not.

A characteristic example begins with Selin wondering why everyone is so happy her cousin had a baby: “I was told: ‘But if she hadn’t had Erol, we wouldn’t have Erol.’ I didn’t have anything against Erol; he was a baby. But hadn’t everyone gotten along fine without him?” She eventually spins this out to a frustration with her supposedly ambitious and smart peers:

“It was a great disappointment to find that even at Harvard, most people’s plan was to have children and amass money for them. You would be talking to someone who seemed like they viewed the world as a place of free movement and the exchange of ideas, and then it would turn out they were in a huge hurry to get everything interesting over with while they were young.”

Batuman’s skill lies in how she leverages Selin’s youth: she is ignorant enough to have a lot of questions, curious enough to ask them, and arrogant enough to believe she’s finding the right answers.

Selin does not have tiered priorities regarding her career and her personal life. Her goal is to be a novelist — it has been since she was a child. She recalls having Frog and Toad books read to her and feeling frustrated at their unwillingness to answer questions like whether Frog “really wanted to get better, or whether he benefitted in some way from Toad’s unwellness.” As good an inspiration as any.

As the entanglement with Ivan drifts out of view, Selin focuses on doing many different types of things and meeting many different types of people so that when the time comes to put pen to paper she’ll know enough about the real world to convincingly create a fake one. This is a nice trick for Batuman: it gives her some rope as a writer to indulge in numerous freewheeling observational passages because there is real grounding in her character. Selin is a narrator whose book you’d actually want to read, a rare offering even in an era lousy with thinly veiled autobiographical novels.

The character most frequently spared from Selin’s cutting observational gaze is Selin. While she is just making her way through college, reading books and being annoyed at her friend’s boyfriends, this isn’t much of a problem. Things are happening to and around her and her participation is somewhat incidental. This isn’t always the best setup for thrilling novel writing but Selin’s narration is pitch perfect.

The problems, ironically, come when Selin begins living a more active life. As she’s traveling across Turkey, sleeping with weird guys she encounters along the way, and navigating the myriad ways men around the country deny her agency, the rapid-fire monologue that’s been carrying readers through all of Either/Or wanes.

One egregious example: Selin, after a few days sleeping with an acquaintance, decides she’d like to move on without him. She ditches him in the hotel room and tries to buy a bus ticket. But the clerk remembered that she was with a guy the day before and “when I said I needed one bus ticket, not two, he just laughed and wouldn’t sell me a ticket, or say anything else, or acknowledge anything I said.” She returns to the hotel and spends the day with the man she was trying to leave. She goes back to the bus station the next day and a different clerk sells her a ticket. This ordeal takes less than half a page. In a book where insignificant moments are teased out for pages, the restraint makes a moment that should be tense or consequential feel empty.

Without access to the details of Selin’s inner life, Either/Or lacks the texture that makes the first two-thirds irresistible. Batuman’s prose is still sharp and funny, but the novel is merely competent.

In the same N+1 essay where she defined the novel, Batuman chides American writers for their short stories that “seemed to have been pared down to a nearly unreadable core of brisk verbs and vivid nouns.” I don’t think those stories or this book are nearly unreadable. But especially contrasted with the exceptional majority of the book, it seems as if readers are being rushed to the end.

It’s a rare book that prompts one to think: this was more exciting when the narrator was trapped in boring conversations than when she’s having a bunch of sex. But that’s the way it is. Batuman, after all, was right. Either/Or is best when it’s made up of irrelevant garbage.

Bradley Babendir is a fiction writer and critic.