Lately, I’ve been trying to dig out the artifacts that matter to me in an effort to understand why they do. A new year is a good time to take stock, figure out what you wish to take with you and what you prefer to consign to the past. The things that stick, I’m finding, are the ones that stand up to a bit of embarrassment. Take Pearl Jam. Not exactly the coolest band in the world to love — maybe never, but certainly not at this point. While the ’90s have been pilfered and dissected for the parts that are still saleable or “obscure” enough to be repackaged, in that specific arena, you don’t get much more mainstream than Pearl Jam.

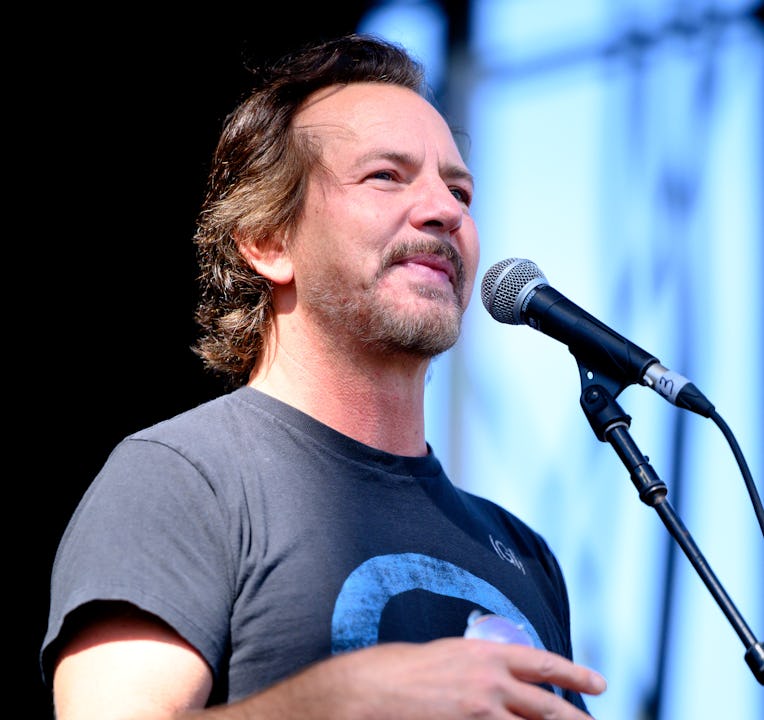

Everyone has their own low-effort Eddie Vedder impression, which garners the kind of chuckle that comes from having an immediate familiarity with what’s being made fun of. Far removed from their pissed-off early days, when they boycotted Ticketmaster and refused to make music videos for MTV, the band is more normie than transgressive. What they do have, even through all the impersonations and sanded-down, lib dad rock they churn out these days, is Vedder himself, the real deal.

I tend to listen to a short rotation of Pearl Jam tracks, specifically “Release,” “Animal,” “Red Mosquito,” “Given to Fly,” “Once,” and “Better Man,” but it’s even more specific than that. Those first two-plus minutes on “Release” that incline up towards “I’ll ride the wave where it takes me,” Vedder staying in his low range until he shreds the last word into oblivion and holds the note like it’s slipping through his fingers, before he goes into a more typically impressive, smoother belt on “Release me.” That second chorus on “Animal” where Vedder does his feral, guttural, shake-your-hands-out growl of disgust after “Why would you wanna hurt me?” that always sounds funny for how primal a noise it is for a human to make and also insanely sexual because Vedder was blindingly hot in his 20s and 30s and one can’t help but wonder if he made similar sounds behind closed doors. Couple that with the final minute of “Red Mosquito,” that guitar solo that opens widescreen down the end credits of time with Vedder singing “If I had known then what I know now,” alchemy captured for the few truly synergetic moments in the band’s history when the music and the voice of Pearl Jam come together perfectly, and then the song just ends. I heard “Given to Fly” in a documentary that I think Matt Damon narrated, so I can’t claim anything deep there, though it’s a beautiful song, bedside storytime soft and contemplative, like being in the ocean and looking up at the sunlight filtering through.

Eddie Vedder has always seemed, to me, an odd person to lead a band like Pearl Jam. His voice betrays contradictory contexts, both otherworldly in its grandeur and utterly pedestrian, sometimes one quality right after the other, sometimes with the two threaded together until he pushes his vocal chords right up to the point where they’re rubbing together so fast you can only envision a blur in his throat. And that’s odd to me because the music Pearl Jam plays can seem so incongruous with Vedder’s pipes on top of it, no matter if it’s the jammier stuff or those precise, thrashing bursts. “Gravelly” doesn’t begin to cover it — Vedder sounds like someone dug him up out of the ground, earthy, heavy, alternately solid or cracking depending on how much water he’s been given. Despite all the easy punchlines about it, you don’t stick around this long, accumulating a huge bag of bangers, and fuck-you sized crowds 30-plus years after your heyday by being a joke.

I’ll admit that “easily irrelevant dad rock” is how I initially thought of Pearl Jam and the ghost of that impression still lingers when I listen to more recent songs like “The Fixer” or “Dance of the Clairvoyants,” where Pearl Jam sounds like a band whose “Influences” section on their Wikipedia lists Pearl Jam. I like Vs., album number two, and bits of Vitalogy and No Code, albums three and four, but there’s a stark fall-off in the thing I listen to them for, namely, Vedder’s Voice of God. Maybe it’s more like the Voice of Jesus and Chris Cornell had the Voice of God because Vedder is, above all, a singer of sympathies, penning stories of his fellow man that aren’t portraits of hardwon American life so much as considerations of different modes of struggle, pain, isolation and really, Vedder is the thing that keeps Pearl Jam from the precipice.

There are great bands with good singers and vice versa. Joe Cocker didn’t need a band behind him, you’d fork out a healthy paycheck portion just to watch him read from a vacuum manual. If Vedder died tomorrow and the group tried to replace him, they’d have to beg for a miracle, the Biblical kind, not whatever you call finding your wallet under a seat at the movie theater the day after you left it. It’s unfair, almost lazy to describe Vedder’s voice as distinctive. You can confuse untrained, amateur gusto with weirdness or originality, but that doesn’t make it good. There is no shortage of stuff to listen to these days, but the edges are either sanded down or artfully tacked on and there is nothing artful about Eddie Vedder’s hangdog singing. Sometimes he croons so warm and vulnerable, you have to wonder if Vedder just finished a good cry. Sometimes it’s so broken up and angry that the only image you can see is a stalk of sugarcane separating into individual fibers before bursting into a cloud of dust, though it’s not just the image, but the sensation, fury and that hilarious moment before you realize you’re about to have a serious freak-out. I prefer the latter sensibility, which is really relegated to the first two albums, maybe the first four if you’re counting lyrics along with delivery.

Speaking of delivery. Vedder’s origin story — a gas station attendant who befriends former Red Hot Chili Peppers drummer Jack Irons, who tells him to audition for a new band up in Seattle, but before getting the gig that would become Pearl Jam, ends up singing backing vocals and a duet with Chris Cornell in Temple of the Dog— makes him sound like a kid off the Greyhound who wandered into the studio one day and happened to be holding the voice of a generation in his pocket, a nothingman all pretty and gift-wrapped. But he deployed his voice without any sense of preciousness, which is why those first few albums have so many moments of danger in them. Yeah, there’s a lot of cringe there, especially if you peer beyond the garbled veil of Vedder’s creative pronunciation and find plenty of obvious, lame lyrics (the American gun rights critique on “Glorified G,” where Vedder sings “Double think, dumb is strength” always does the trick). Doesn’t really matter, the better writing comes later. It is unfortunate to think that, for all the recognizable features of his delivery that Vedder still retains, the energy of his early days never burned long enough to connect up with his best songwriting. Of course, those who have stuck with the band after all these years reap enormous benefits because Pearl Jam still makes music and puts on the kinds of shows that recalibrate your understanding of what live music can be, how communal it can actually feel, how weird of a band they really are. But, man. The early stuff.

I’m writing about Vedder like he’s dead and it’s probably silly to hold up his younger self like a vintage t-shirt and say “See how much cooler! Hotter! More alive!” I’m genuinely in thrall to the guy. It takes a quality beyond skill and creativity to make something as ephemeral and strange as music stick in your head. Which means that, for all the sick licks and timeless melodies, Pearl Jam could never do it without the English that Vedder spins on top of every one of their songs, even the really dumb ones, even in his craggy years, even when playing the hits that kids only know from their parents or the radio or Youtube compilations of ’90s music. After all, beyond nostalgia, there has to be a more sincere reason why they still get played, referenced, parodied, emulated, right? I think when I was younger, the idea of having my list of favorite bands including Pearl Jam seemed mortifying. Now, I want to introduce Eddie Vedder to my kids one day. I want them to play “Release” at my funeral.

Nicholas Russell is a writer from Las Vegas. His work has been featured in The Believer, Defector, Reverse Shot, Vulture, The Guardian, NPR Music, and The Point, among other publications.