In 1921, D.H. Lawrence visited the Mediterranean island of Sardinia, a short boat ride from his home base in Sicily. He went to escape, not only from “these maddening, exasperating, impossible Sicilians,” as he would write in his account of the journey, Sea and Sardinia, but also from an almost claustrophobic sense of stasis. “Comes over one an absolute necessity to move,” he declares in the book’s opening sentence, just the first of many volcanic utterances that litter the Lawrentian landscape. Actual volcanoes and sunsets and coastlines are featured throughout this slim travel book, but none of these quite compare to the spectacle of Lawrence himself.

“Comes over one an absolute necessity to move” — a sentence that is head over heels with impatience, as if he is already half out the door. Lawrence has no patience at all, not for those maligned Sicilians, certainly, nor for much else. Bad food, high prices, loud children: they all lodge under his thin skin, to be dwelled on with mounting fury, like an itch that has been scratched so much it bleeds. The first meal he takes on the boat to Sardinia with the q-b — short for queen bee, his nickname for his equally tempestuous wife Frieda — is not the rustic deliciousness a modern reader might expect. “Bash comes a huge plate of thick, oily cabbage soup, very full, swilkering over the sides,” he writes. Next course: “a massive yellow omelette, like some log of bilious wood.” And then: “a long slab of the inevitable meat cut into innumerable slices, tasting of dead nothingness and having a thick sauce of brown neutrality.” Anthony Bourdain, this is not.

But perhaps nothing annoys Lawrence more than the various manifestations of modern life. Machinery, currency exchange rates, suit and tie, democratic ideals, socialist agitation — all corrupt, all suffocating to Lawrence. Modern life is another cage that Lawrence must escape; modern life, carrying with it the long train of Western civilization, is responsible for the stagnant air of Sicily. So he must go to Sardinia, a green jewel outside time and history, “outside the circuit of civilization,” an autonomous zone between Africa and Europe. “Belonging to nowhere, never having belonged to anywhere,” he writes.

And yet, even there, on an enchanted island on the far edge of the world, his impatience boils over. His trail northward, from Cagliari to Mandas to Sorgono to Terranova, has since been memorialized with a series of plaques, as if Lawrence had been on some holy pilgrimage, when what his chronicle conveys is a litany of pedestrian complaints: about the dismal lodgings (“Ah, the filthy bedroom”), the locals who drive him crazy (“I instantly hated him for the filthy appearance he made”), the extortionate cost of everything (“Italy wants to mill you into filthy paper Liras”).

Impatience lies at the center of a galaxy of related traits. Lawrence is both compulsive and impulsive. He is quick to anger, quick to irritation, quick to let fly. He lives at emotional extremes, dripping with disgust when he is disgusted, soaring with joy when he is moved. (And, despite his dyspepsia, he is often moved, by a beautiful boat made from “living-tissued old wood,” for example, or by the “hot eyes” of the blossoms on the almond trees.) He brims with English condescension toward the undifferentiated Sicilian masses — “the most stupid people on earth,” he says — yet is wounded to the core that they cannot discern the unique individual that lies behind his outward Englishness. “I am not the British Isles on two legs,” he sniffs.

Lawrence roars to life on the page in a way that most writers do not.

He has opinions, strong ones, loads of them, and he flings them heedlessly, seemingly without reflection, as if the lightning quickness with which they bolt from his mind is evidence of a more spontaneous, more electric kind of truth. Sometimes this results in oddly felicitous imagery, such as when he comments, with distaste, on the Italian penchant for physical displays of affection: “They pour themselves one over the other like so much melted butter over parsnips.” But at other times, he can be plain mean or idiotic or bigoted, such as when he seethes at a boatman who has the temerity to haggle over the price of a fare: “the hateful, unmanly insolence of these lords of toil, now they have their various ‘unions’ behind them and their ‘rights’ as working men, sends my blood black.”

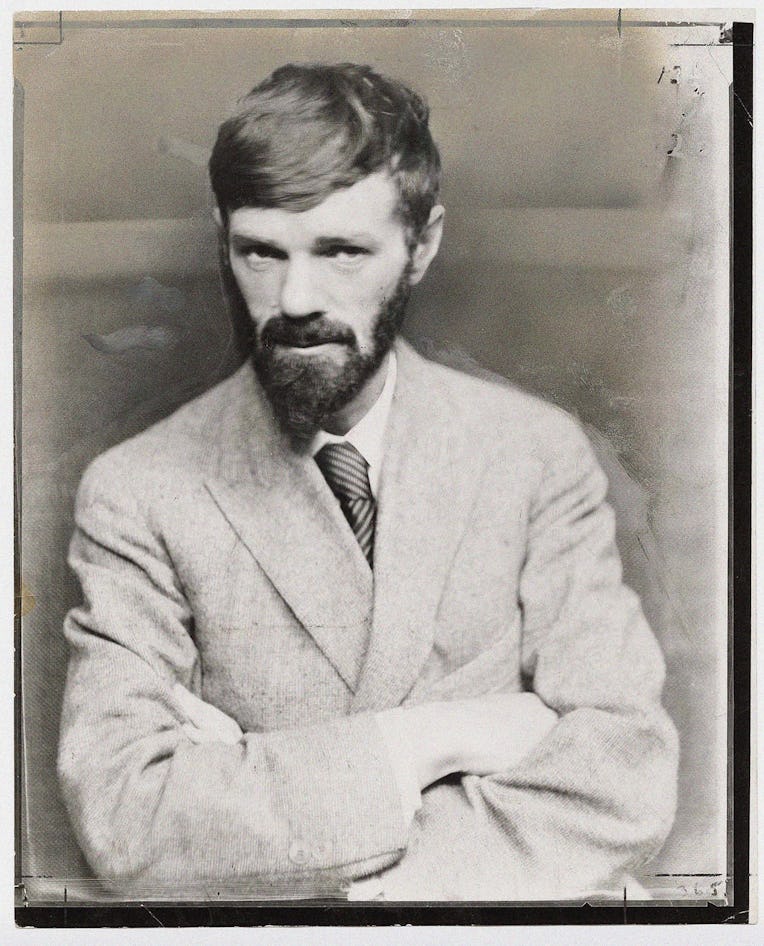

Lawrence, in other words, is an ego unbound. There is never a moment when he is not overwhelmingly himself. There is no shaming him into hiding even one iota of who he is; every flaw, every prejudice, every tawdry thought, is on display. This is the less romantic side of what Geoff Dyer in his famous study of Lawrence, Out of Sheer Rage, called “one of the most hackneyed aspects of the Lawrence myth”: his lifelong quest to shake off the constraints of history and convention to more fully become himself. Or as Lawrence himself put it, “the real Me I shall achieve, that is the consideration.”

In this respect, there may not be a writer more ill-suited for our times than David Herbert Lawrence. This is not because he appears to loathe egalitarian values, is prone to quasi-fascistic sentiment, and pines for the kind of tribal violence that would tear Europe asunder in the subsequent decades. (“Men will set their bonnets at one another now, and fight themselves into separation and sharp distinction … Hasten the day, and save us from proletarian homogeneity and khaki all-alikeness.”) Those of us on the liberal-left spectrum can accept that a man writing these things one hundred years ago has a politics that are less enlightened than ours, particularly when those politics are so idiosyncratic. (Those on the right, of course, may find that Lawrence’s ravings perfectly echo their own thoughts and beliefs on various matters.) No, the reason Lawrence is so out of sync with our moment is that to be one’s self all the time, to give no quarter to society’s values, is to be a monster.

Perversely, Lawrence’s monstrousness is what makes Sea and Sardinia such entertaining reading. That, and some very fine writing. In fact, I suspect that these two qualities are not unrelated. Lawrence roars to life on the page in a way that most writers do not. He is an indelible presence, and if the years have done their damage to his opinions, he himself has endured as a monument, as robust as the day his words were first set on the page. He is not an angel, but an angel — pure, aloof, perfect — is the opposite of what a man is. The comedic pathos of this book comes from the fact that I, too, am full of flaws and prejudices, even if I will never admit them in public.

It would be impossible these days for anyone to write from so wholly within himself. This is an age in which every sentence is scoured for stupidity and bigotry, embarrassing passages are screen-captured and mocked on Twitter, and writers have taken to denouncing their own defective works. Thanks to social media, everyone is hyper-aware of what everyone else thinks and what a given piece of prose will do to their mentions, which means the audience’s gaze is upon the writer even when he is deep in his solitary vocation. Privileges are checked. Blind spots are detected and compensated for. All these other people — friends, critics, colleagues — creep into what is supposed to be an expression of the self. Perhaps “self-censorship” is too strong a word to describe what takes place, but there is a kind of self-stifling that Lawrence would never have stomached. (Notoriously, he had actual censors to worry about.)

At the same time, this is the era of the confessional, the personal essay, the autofictional novel, all of which are thriving despite premature declarations of their demise. There has never been such demand for writers to spill their darkest secrets and deepest fears, to indulge the ego and its voracious clamor for recognition. I would say this tension between self-stifling and self-baring is a paradox, were it not for the fact that the latter is accompanied by the same measure of self-awareness. The first-person dispatch is now fully conscious of what its revelations are meant to achieve, giving a premeditated aura even to the antics of supposedly transgressive writers in a supposedly transgressive scene. Contemporary writers like Jenny Offill and Sheila Heti have committed to behaving like selfish “monsters” in the name of their art, which is very different from just being one.

What I find captivating about Lawrence is that he leans so heavily into that mix of self-delusion and self-belief that is necessary for any successful artistic endeavor. He sincerely believes that he is in the right, even when he is so laughably in the wrong. It is hard to imagine someone these days writing Lawrence’s exchange with a street urchin who has carried his bags to his hotel room. Lawrence gives him three francs. The urchin, hoping for five francs, “looked at it as if it were my death-warrant… Then he extended his arm with a gesture of superb insolence, flinging me back my gold without a word.” Lawrence is enraged, appalled. “The brat!” he thinks. “The brat!” He then cries, “What a beastly little boy! What a horrid little boy!” The boy quails. He takes the three francs. “And now, in final contempt,” Lawrence writes, satisfied that the boy has been properly shamed, “I gave him the other two.”

Horrible stuff. No sympathy for the poor boy. No attempt to step in his shoes. Not even a hint of guilt, only a desire to shower him with scorn. And we are talking about exploiting a child’s labor no less. Yet it is an amazing comic interlude, steeped in Lawrence’s pettiness. The punch line is that he later finds out the other boys did not even get one and a half francs. His suspicion that he is being bilked, that he is the victim, is resoundingly confirmed.

Lawrence flees to Sardinia to escape modernity. He is in search of a more essential existence, of a “world long gone by, lingering as legends linger on.” He catches glimpses of this world, in a valley of almond trees, in the “long, slow slide” of a ship falling into a wave’s trough, in a Sardinian peasant in the fields, “working alone, as if eternally.” At one point he writes, “And my nostalgia for something I know not what was not an illusion.” To read Sea and Sardinia is to also inhabit a long-lost world, one that we should be happy to have left behind. We have heard a lot from the likes of Lawrence; it is time to listen to the urchin’s side of the story. But there is always a cost to progress. In what may be his only moment of self-awareness in the entire book, Lawrence says, “The judgment may be all wrong: but this was the impression I got.” Unfortunately for us, it is in the impression, not in good judgment, where the value of literature often lies.

Ryu Spaeth is an editor at New York magazine.