Big Screen, Big Worms

How these cinematic creatures burrowed their way into our collective nightmares.

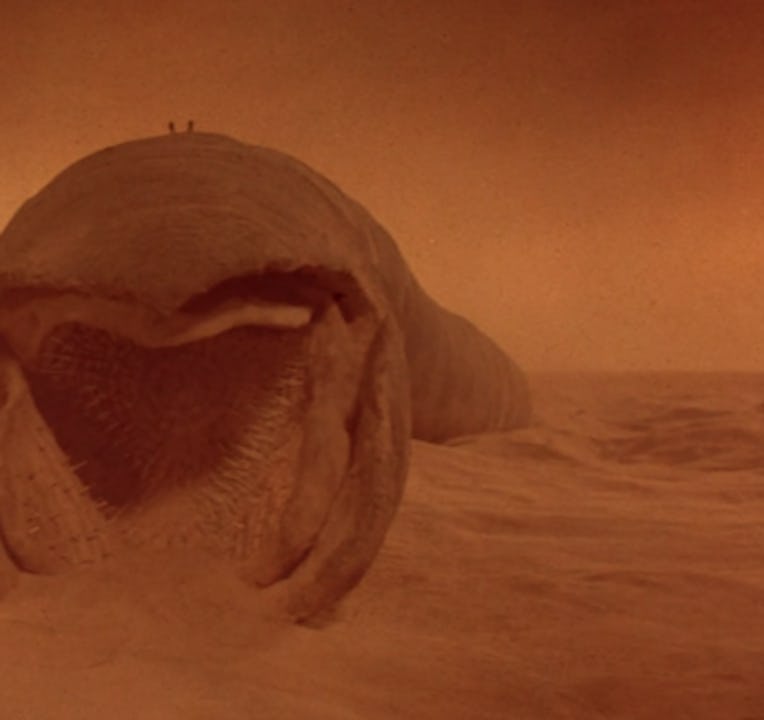

The sandworms of Dune, the book, are almost too horrible to contemplate in full. Instead, they are experienced through secondary effects (something beneath the sand creating water-like crests, a pungent smell of cinnamon) or in part (crystal teeth in a “giant, questing mouth”). The sandworms of Dune, the movies (both David Lynch’s somewhat tortured 1984 adaptation and Denis Villeneuve’s forthcoming) are fully embodied and maybe a little more viscerally corporeal than readers had imagined. Lynch’s worm, with its beak-y mouth, has been described to me by the cultural critic Leo Braudy as evoking Kermit the Frog. The newest sandworm, Vulture’s Alison Willmore writes, "left its old vagina dentata influences behind only to end up resembling a giant asshole."

The Dune sandworm gets no respect as a cinematic icon, considering that its footprint — or, wait — is all over every subsequent large creature that has burrowed its way into our nightmares. There’s the giant, oddly dry body, multiple jaws that open wide like a carrion flower, the vortex of teeth that emerge from its mouth like a second head (or a literal second head). Alec Gillis, co-founder of Amalgamated Dynamics Inc., who designed the beloved graboids from Tremors, recalled that at the time, “the big example on (under?) the landscape at the time was Dune’s sandworms.” Its hold on movies can be traced back over the decade leading up to Lynch’s Dune, in which several directors imagined ambitious adaptations that ultimately stalled out. And when you really think about it, giant horror worms share a heritage that taps into our mythologies and anxieties, and goes back to the Cambrian explosion millions of years ago when a huge diversity of animal life first appeared in the fossil record, including some very freaky worms.

The sandworm — which is (as far as anyone in Dune can remember) native to the desert environment of Arrakis and is territorial but decidedly not carnivorous — is not a natural blueprint for an archetypal horror monster. It’s only scary when it becomes very large and can fit very large things in its mouth. Still, it’s arguably the most mainstream representation of a worm as a striking on-screen beast, which got things rolling toward the multi-jawed terrors that showed up in way too many movies billed as kid-friendly. Perhaps the first to see the sandworm’s potential was the artist H.R. Giger. In 1975, Alejandro Jodorowsky assembled a team of set and character designers including Giger for his admirably bonkers planned Dune adaptation. There, Giger met screenwriter Dan O’Bannon, and when O’Bannon went on to write Alien, he drew Ridley Scott’s attention to Giger’s work, says Andreas Hirsch, an author, curator, and photographer who wrote the essay for the only comprehensive monograph of H.R. Giger. Giger worked with Scott on his 1981 Dune attempt too, drawing one piece of concept art for the sandworm: a ferocious-looking version with daggered teeth and armor-like scales.

Dune fit neatly into Giger’s interests: literature, psychedelic drugs, anxieties about environmental degradation, and creating detailed biological cycles for his imagined creatures. “H.R. Giger had cultivated the exploitation of the subconscious — including nightmarish dreams — to an extreme point, which allowed him to turn archetypal fears into an entire bestiary of creatures,” Hirsch told me. Though Giger’s worm didn’t make it into Lynch’s Dune and in fact looks a lot more like Villeneuve’s worm with its sharp tooth-encircled mouth, his fascination with it and his other horror visions, like the second set of retractable jaws belonging to the aliens of Alien fame, influenced many a worm after. For a period in the ’80s and ’90s, worms seemed to pose an interesting challenge to makers of horror and sci-fi movies, who have never passed up an opportunity to scarify completely arbitrary things like refrigerators and donuts. Dune was just one of the first to prove that to make worms scary, you don’t need to look further than real-life biology.

Distinct from the Blood-Sucking or Mind-Control Worm (Slither, Star Trek), which play on parasitic worms, the Giant Violent Worm references the invertebrates’ hunter-burrower class, like the Bobbit worm, which waits to attack prey. Luke Parry, a research and teaching fellow at the University of Oxford who studies the Cambrian explosion, has studied evidence of ancient worms not so different from sandworms. “This group of worms that are ambush predators seem to have just become giant multiple times throughout history,” he told me, delivering a line straight out of the first 30 minutes of a movie about giant worms breaking through the Siberian permafrost or something. Many fossil and current annelids also do have jaws, the feature that seems to most consistently show up in Hollywood. “I guess the easiest way to make a worm scary is to put some hard bits on the front of it,” Parry said. And having more than the usual two jaws adds a certain je ne sais quoi. This was the gist of just about the only direction Gillis got for the Tremors graboids. “The script had very little description other than describing the graboid's mouth as 'opening like a grotesque flower,'” he told me. The head is “mostly based on a snapping turtle, with low-slung mandibles for an otherworldly look.”

Lynch’s sandworm features a similar beak-like set of jaws that open to reveal tiers of small teeth ringing the esophagus (Jeff the subway worm from Men in Black II took a page from that). It resembles an annelid worm, a phylum that consists of ringed and segmented worms, Parry’s favorite. Villeneuve’s sandworm looks more like circular-mouthed priapulida worms, which are “everywhere” in the Cambrian fossil record and, as Google will tell you immediately, sometimes called penis worms (the world of worms is rife with genital symbolism). Villeneuve’s looks more like how Herbert wrote it: a round maw ringed with repeating, circular rows of needle-y teeth (remember, they make knives out of those!). The teeth are so thin and numerous that they resemble the filter-feeding combed mouths of baleen whales, which might make more biological sense, Parry said. “You would need some sort of prey that was big enough to need jaws that big.” Sandworms mostly eat organic material in sand. Jaws are added to scare, though scarier still is how many annelid worms actually do consume food: “Their jaws are contained in the front part of their digestive tract,” Parry said. “They use the fluid pressure in their body to turn the front part of their gut inside out, shoot the jaws out of their mouths, and then pull material back in.” A missed opportunity to pit Zendaya against a truly disturbing sight, if you ask me.

But the sandworm also appeals because there’s so much about it that feels unnatural; a lot of what’s off about it is hard to put a finger on. “The fantasy genres of popular culture, like horror and sci-fi, often deal with unresolved questions, conflicts, and especially fears in the national imagination,” said Braudy, who is also a University of Southern California professor. Maybe we just don’t like creatures without a face: “We cannot properly look such a beast in the eye, we cannot ‘face’ this kind of danger,” Hirsch said. Braudy also draws a parallel to modern-day faceless fears including, you know, viruses. Also unnatural: many famous giant worms, like the Sarlacc from Star Wars, live in the desert, an environment where worms do not live in real life. In fact, a myth that may have inspired the sandworm is the Mongolian Death Worm, a cryptid believed to live, improbably, in the Gobi Desert. The way they move through these arid environments is freaky too, and was a major design factor in Tremors. “The worms needed to be 'terradynamic' to allow them to plough powerfully through the dirt like underground locomotives,” Gillis said. Swimming and diving through sand shows a power over nature that fascinates but also unsettles us, offered Eric Otto, a professor of environmental humanities at Florida Gulf Coast University who has written about the ecological legacy of Dune. “It’s a species that has the capability of machinery beyond anything that we could ever achieve,” he said. “They’re kind of like the weather, or earthquakes — things that make us feel powerless. But in the Anthropocene, we kind of are wielding machines of power analogous to the sandworms, and as such, we are becoming as unsettling.”

Making a viewer feel powerless in the face of a worm is a neat trick. In his book Haunted, Braudy writes that the “process by which the unnatural or just peculiar becomes the horrifying requires an interpreter who sees it as a portent of doom, rather than something merely happenstance or pathetic.” A worm is pathetic when you see it shriveling on the sidewalk, but to the natural world, worms are often a portent of doom. The horsehair worm can reproduce inside an insect host and then burst out of its body (very Giger-like!). But even the earthworm can be a harbinger of chaos. “One thing which is really crucial about worms today is that they often completely modify their own habitats,” Parry said. “People often refer to things like earthworms as being ecosystem engineers.” They metabolize the materials in the soil around them and can change its fundamental properties, sometimes throwing off the plants and other organisms in that soil. (This can be a good thing too—including during the Cambrian explosion, when burrowing worms actually helped mix up sediments in soil with oxygen, making it a less toxic environment for other animals to live.)

Worms, fictional and real, change their surroundings to their needs. They’ve bent Hollywood tropes to their will and they’re at the heart of biodiversity itself. In them we might recognize a natural power we can’t begin to comprehend—maybe even our primordial selves. “Most animals are worms. Even a lot of things that are currently not worms started off as something which was more or less a worm,” Parry said. “And things that stopped being worms at some point, some of those things have gone back to being worms.” So many years after the Cambrian Explosion, it’s still a worm’s world, and we’re just living in it.

Erin Berger is a freelance writer and contributing editor at Outside magazine who lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico.