My grandfather’s uncle, Charles Wetherell, vomited so hard off the side of a ship in 1912 that he fell into the sea and drowned. Some families are marked by greatness and prestige, some by tragedy, and others by secret disgraces. Mine is marked by darkly comic accidents and ironic deaths.

I only learned about my bloodline’s bizarre curse last week, when my Mum emailed me a word document detailing our entire family history. For my Mum, a retired academic, this was the result of more than a decade of research. For years she has been traipsing around dismal archives in multiple countries, collecting dormant diaries from suburban attics and having long conversations on the phone with elderly relatives with Dickensian names like Gertrude Brodrick and Sybil Newth.

My Mum approached this research like it was a well-paced detective novel. She told me that when I was her age I would resent her for having done this work already, uncovering all of our family’s spoilers and leaving no secrets to unearth. In part, this research was a way of leapfrogging her own cold and secretive parents in search of a kinder community to which her life and mine could be tethered.

My Mum is originally from New Zealand and my family’s history covers multiple generations of Australian and New Zealand settlers of British descent, living violent agricultural lives on the remote fringes of an expanding empire. My family’s history is inextricable from the colonization of these two nations, a bleak and familiar story about seizure of native land and the massacre of indigenous peoples. Generations of my ancestors lived in places where they should never have been. They also died there, in ridiculous fashion.

The story begins with the unfortunate life of Thomas Wetherell, my great-great-grandfather. At the age of 44 he sold his farm in Shropshire and all of his possessions. For reasons that remain unclear, he boarded a direct steam ship bound for a remote tropical settlement in Queensland, Australia with his wife and eight children. Three months and tens of thousands of miles later, he arrived, stepped off the boat, and then immediately died of Typhoid. Many died of disease in the late nineteenth century, but few died with such bad timing as Thomas, whose wife, Louisa and children were now stranded for the rest of their lives in a tiny patriarchal frontier town with no source of income.

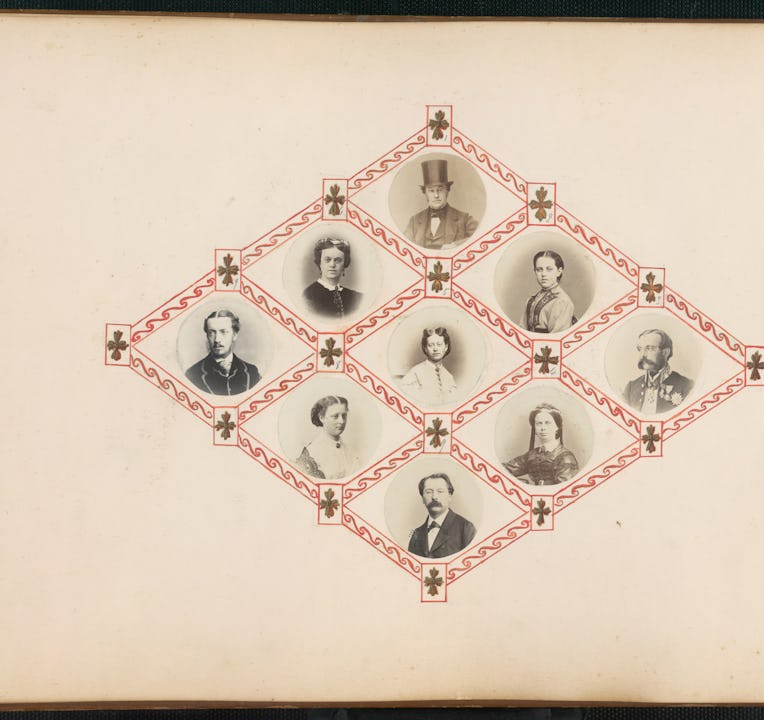

Louisa and children

The same year, on a remote farmstead on the South Island of New Zealand, my great-great-uncle, Norman Brodrick, was working in Invercargill, the rain-swept southernmost point of the country. At the age of 24, Norman was one of the first Europeans settlers to have lived his entire life in New Zealand from birth. He was tending to his mountainous farm when he stopped to drink from a stream. Unbeknownst to him, a little further uphill, one of his own sheep lay dead, rotting in the water. Norman died shortly after, poisoned by his own livestock.

These distant and as yet unconnected strands of my family were speculators, farmers, and in some instances ruthless and reprehensible collectors of indigenous land. The overall impression is of a tribe of people too awkward and provincial to fully grasp the enormity of their own unique historical position. Take, for example, Thomas Strickland, my great,-great,-great-grandfather, who after barely leaving rural Norfolk, emigrated to New Zealand in 1851 at the age of 17 on one of the first few settler boats. After months at sea on a wooden coffin, travelling across the face of the planet to a radically different eco-system and culture, his diary for the day he arrived is almost vertiginously banal: “Beautiful evening and fine sunset, nice and warm, such a difference to the cold evenings we have been accustomed to.”

The next generation of Australians, the Dibdins, fared little better, living lives that were profoundly altered by their refusal to conform to even the most basic of gun safety measures. In 1889, my great-uncle, Tom Dibdin, accidentally shot himself. Tom was riding in a horse-drawn buggy in rural Australia, a rifle perched between his legs, its barrel resting on his shoulder. When the buggy hit a bump in the road, the rifle fired. He survived, but his arm was probably amputated.

Incredibly, Tom was not the only member of the Dibdin family to accidentally shoot himself that year. A few months after this incident, Tom’s father (and my great,-great-grandfather) Robert Dibdin fired a bullet into his chest while cleaning a gun in his shed. According to a newspaper report, Thomas had a charming habit of firing guns alone in his garden during his downtime, meaning that his family thought nothing of hearing ambient gunfire outside. It was only after some time had passed and “some deep groans were heard” coming from the shed that they found him lying in a pool of blood. Miraculously, Robert also survived.

These two accidents have made me think about my own clumsiness. My hands turn to jelly when required to do even the simplest tasks. Putting on socks or a sweater is often an ordeal that leaves me bouncing from wall to wall, sending framed pictures crashing to the ground. Learning to drive has been particularly challenging. In my early thirties I had more than fifty hours of driving lessons, after which time my driving instructor, who had worked for twenty years, quit her job in despair. I still haven’t passed the test. As I read my Mum’s document in my apartment, surrounded by tiny overlooked shards long ago broken mugs and glasses, I wondered if my clumsiness was an inheritance from the ham-fisted, trigger-happy Dibdins.

Then there’s Charles Wetherell, the man who drowned after vomiting off a ship. This, at least, was the verdict of a coroner’s inquest. Charles vanished off the face of the earth in 1912 in the middle of the night during a long steam ship voyage along the coast of Australia. He had become extremely seasick and went up to the deck to get some air. He was seen by another passenger lying prostrate over a seat at 2:00am, and shortly afterwards by a sailor who saw him vomiting furiously over the ship’s railings. Charles was very tall and not very sure-footed, and the likeliest explanation is that he slipped over the low railings after an especially dramatic hurl.

I have always been irrationally afraid of throwing up, associating vomiting with death. When drunk or ill I have frequently suppressed the urge to be sick, long past the point at which I’d feel much better if I did. After finding out about Charles’s fate last week, I now wonder whether this is some deep epigenetic scar, a warning signal sounding through the historical darkness.

Charles’s death, while a tragedy, at least meant that he escaped the impending horror of the First World War. Hundreds of thousands of Australians and New Zealanders were enlisted to fight, ten to fifteen percent of whom would never return. The reason I am currently alive could well be due to my great-grandfather’s “poor physique” which meant that he failed the medical exam for enlisting (even more impressive given this was probably quite a low bar). Most of these deaths occurred in Gallipoli, a catastrophically organized bloodbath in Turkey in 1915. Three of my relatives fought on the same beach during this campaign, two from New Zealand and one from Australia. At the time they were strangers to each other, but their lives would soon be reconfigured through future marriages and bloodlines.

While three of my relatives died in the war, the death of Tom Field, another great,-great-uncle, stands out. By a stroke of luck Tom fought in, and survived, the Battles of Messines in 1917. Like much of the war, this event was a carefully orchestrated exercise in symmetrical mass slaughter, in which more than 50,000 people died in order to capture a few miles of dismal hillside in southern Belgium. Tom wrote a breathless report of his survival for the Invercargill local newspaper, an account that drips with a sympathetic mixture of extreme relief and terrible trauma. He described the battle as “magnificent and yet awful and one wonders if it really is a civilized world.” Less than two weeks later after his miraculous survival, Tom was randomly killed by an errant German shell on a quiet night while filling up his water bottle on a non-combat related assignment.

Tom Field

Finally, and perhaps most astonishingly, my great-uncle Harry Wetherell was eaten by a shark in 1929. Harry was 18 and was swimming on a remote island beach in Australia. There is a popular family story that when the shark attacked, Harry’s last act was to warn others on the beach to evacuate, a story that I choose to believe is true. Being eaten by a shark is a preposterously rare event. Between 1958 and 2016 there have only been 418 recorded fatalities from shark attacks anywhere in the world. This works out at just over seven deaths a year. To put this in perspective, about 500 people are killed by hippos each year, 2,000 people from lighting strikes and 13 from toppling vending machines.

My Mum opens her family history with the novelist Julian Barnes’ quote that “biography is a collection of holes tied together with string.” The lives and strange deaths of my relatives were made visible by the new administrative technologies of Britain’s expanding imperial state – census returns, military records, obituaries in small frontier newspapers. These are shallow and fleeting representations of rich interior lives which will remain forever unknowable. It is extremely possible that some of these deaths contain even darker secrets. When Charles Wetherell fell into the sea in 1912, for example, the weather was described as being unusually calm.

My relatives were also implicated in the day-to-day historical violence that made the modern world. They were beneficiaries of the first great wave of fossil fuel driven globalization in the late nineteenth century. As descendants of some of the first European arrivals in New Zealand, they displaced and subordinated Maori settlers, participating enthusiastically in the carpeting over of landscapes with ancient meanings by tract suburbs named after white property speculators. For many of the women in my family, the picture is also less clear. Their names evaporated like mist from the historical record when they married and with no jobs or by-lines or military records their complex lives and perhaps even their dramatic deaths remain invisible.

In the week since reading these stories, I have thought often of this strange community of the dead and wondered about my own fate. Like so many of my male relatives, am I also due a ludicrous, irony tinged and extremely historically specific death? To paraphrase Karl Marx, who died of bronchitis in London in 1883, just a few months after Thomas Wetherell arrived in Queensland, men make their own deaths, but not in circumstances of their choosing.

Fortunately, I think I have discovered a new justification for my own cowardice. Much to the frustration of countless friends and loved ones, I’ve never been one for swimming in the sea, or boat rides, or firearms, or long trips into the natural world. Like a note written by my mother excusing me from PE, I now have generations of supporting evidence in favor of my decision to live a calm, risk-free, and happy life mostly indoors.

Sam Wetherell is a historian of Britain who works at the University of York. His most recent book, Foundations, How the Built Environment made Twentieth-Century Britain, is out now with Princeton University Press.